Exploring Athens’ Flourishing English Comedy Scene

At the Athens English Comedy Club,...

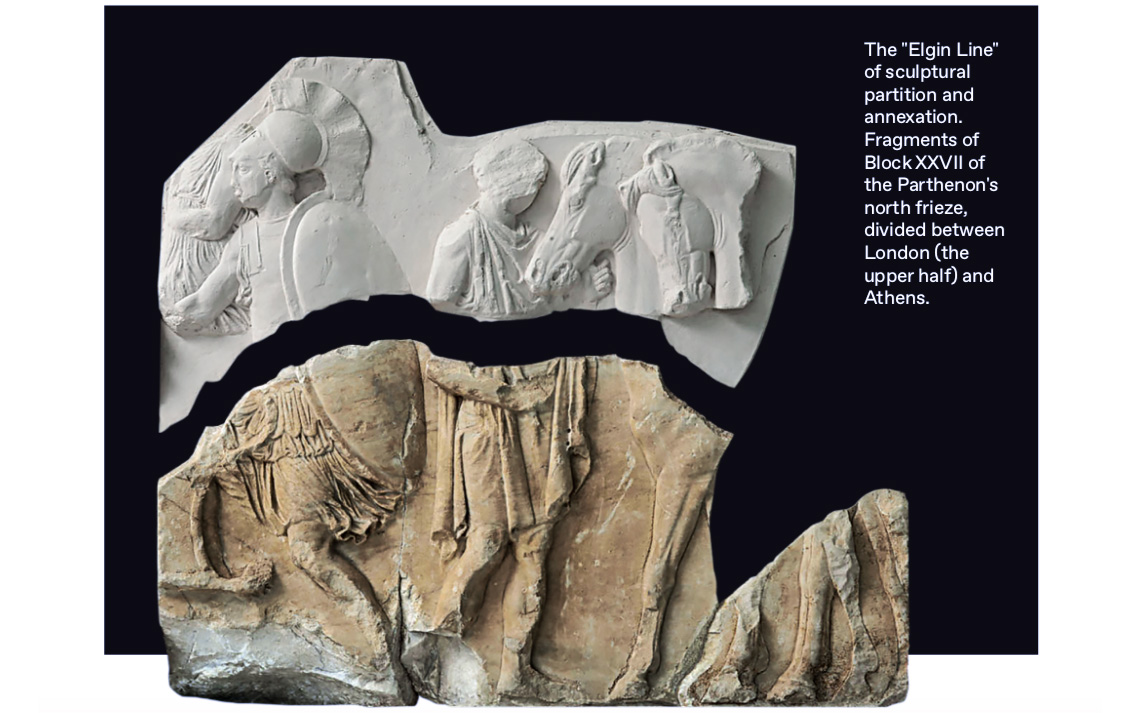

Surviving sculptural elements from

the Parthenon's east pediment and metopes. From 1801 to 1804, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, embarked on a systematic campaign to strip the ancient monument of its sculptures, later selling them to the British Parliament for £35,000.

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

At the end of September in Mexico City, in front of a packed assembly, Lina Mendoni, Greece’s current Minister of Culture and Sports, addressed the 41st UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Policies and Sustainable Development (MONDIACULT 2022). In her speech, which showcased recent Greek initiatives in the cultural heritage field, she reiterated her country’s longstanding request for the return of the 2,500-year-old Parthenon sculptures from the British Museum in London, where they have been on permanent display since 1817. Aside from all the legal arguments successive Greek governments have made over the years, Mendoni emphasized that the issue is one of simple ethics and justice, of “respecting and preserving the authenticity, unity, and integrity of cultural heritage.”

Her succinct words cut to the heart of the dispute, mirroring those of a predecessor of hers, the late Melina Mercouri, who launched the reunification campaign at the very first MONDIACULT conference in 1982, again in Mexico City, with this passionate plea: “I would like to remind you that in the case of the Acropolis Marbles we are not asking for the return of a painting or statue. We ask for the restitution of part of a unique monument, the particular symbol of a civilization. And I believe that the time has come for these Marbles to come home to the blue skies of Attica, to their rightful place, where they form a structural and functional part of a unique entity.”

Out of the four decades since Mercouri brought the Parthenon sculptures’ plight to the world’s attention, the last 12 months have arguably been the most dynamic, witnessing an upsurge in activity that has once again thrust the issue into the spotlight. Working in close support of the Greek authorities since the early 1980s, groups of dedicated campaigners from abroad, gathered together in national committees (currently 21 groups spanning 19 countries) under the collective umbrella of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), have played a significant role in keeping the issue in the public eye. Hosting lectures and conferences and staging protests, these committees comprise academics, lawyers, journalists, media personalities and others, all committed to securing the sculptures’ return to Greece.

Preeminent scholars Dr. Christiane Tytgat and Professor Paul Cartledge, Chair and Vice-Chair of IARPS respectively, have dedicated their careers to studying ancient Greece. Here, they talk about the enduring democratic symbolism of the Parthenon, the current state of the reunification campaign, and why it is crucial to continue to raise awareness and exert pressure on the UK authorities and the trustees of the British Museum. Through the lens of contemporary post-colonial thinking, they examine why, more than ever before, there is reason to be optimistic that Pheidias’ extraordinary sculptures, conceived during the Golden Age of Athens in the 5th century BC and unceremoniously wrenched from the monument by Lord Elgin and his associates in the early 1800s, will soon be coming home “to the blue skies of Attica.”

Christiane Tytgat, Archaeologist and historian, and Chair of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures.

Paul Cartledge, Cambridge classicist and Vice-Chair of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures.

Christiane Tytgat (CT): The original Parthenon (or “Pre-Parthenon”), indeed all the temples of the sacred precinct on the Acropolis of Athens, were destroyed and burned by the invading Persians in 480 BC. They were only rebuilt by decree of the demos – the people – decades later, in the second half of the 5th century. As such, the Parthenon is the ultimate symbol of the power to which Athens rose at that time, thanks to the democratic system established by the lawgiver Cleisthenes (ca. 570-508 BC), which evolved over the 5th century, as acknowledged by contemporary writers Herodotus and Thucydides.

The monument has dominated the Athenian skyline for nearly two and a half thousand years and can be seen from every direction when approaching the city; no wonder it is considered a “beacon.” Nevertheless, one might ask whether the notion of it being a “beacon of democracy” is more of a modern invention from the 19th century. While Herodotus and Thucydides wrote about democracy and how it worked, they never mentioned the Parthenon in that context. In fact, there is very little written about the monument in the ancient sources, aside from Plutarch (ca. 46-119 AD) and Pausanias (ca. 110-180 AD), which is quite odd. The Parthenon as a symbol of democracy is, in my view, more closely associated with the age of national struggles and revolutions in the 19th century, as newly forged independent states sought inspiration for their own modern constitutions. Let us hope it will continue to fulfill this role, especially now, as we face enormous challenges in Europe.

The Acropolis of Athens.

© Shutterstock

Paul Cartledge (PC): The Parthenon is and remains a universal symbol of democratic hope – to which I would add just one crucial qualification: the original ancient Athenian democracy that produced the Parthenon is not our modern Western (representative) democracy. On the one hand, their democracy was more democratic than ours – it was direct. On the other hand, ours is more democratic than theirs – we have full adult suffrage, so it is more inclusive, whereas their notion of democratic citizenship was exclusive (i.e., male-only), and they had slaves, lots of them.

The Athenian statesman Demosthenes, writing in the 4th century BC, referred to the Parthenon as an everlasting emblem of resistance against the Persians in its original context and a symbol of defiance in the face of rapidly expanding Macedonian power in his own time. He idealized the Parthenon (and Athenian democracy) to motivate his fellow citizens, as the inheritors of “possessions that will never die,” to stand firm against Philip II of Macedon, a staunch autocrat. In its modern context, its symbolism is also nationalistic and can be associated with the Greek struggle for independence from the Ottoman empire.

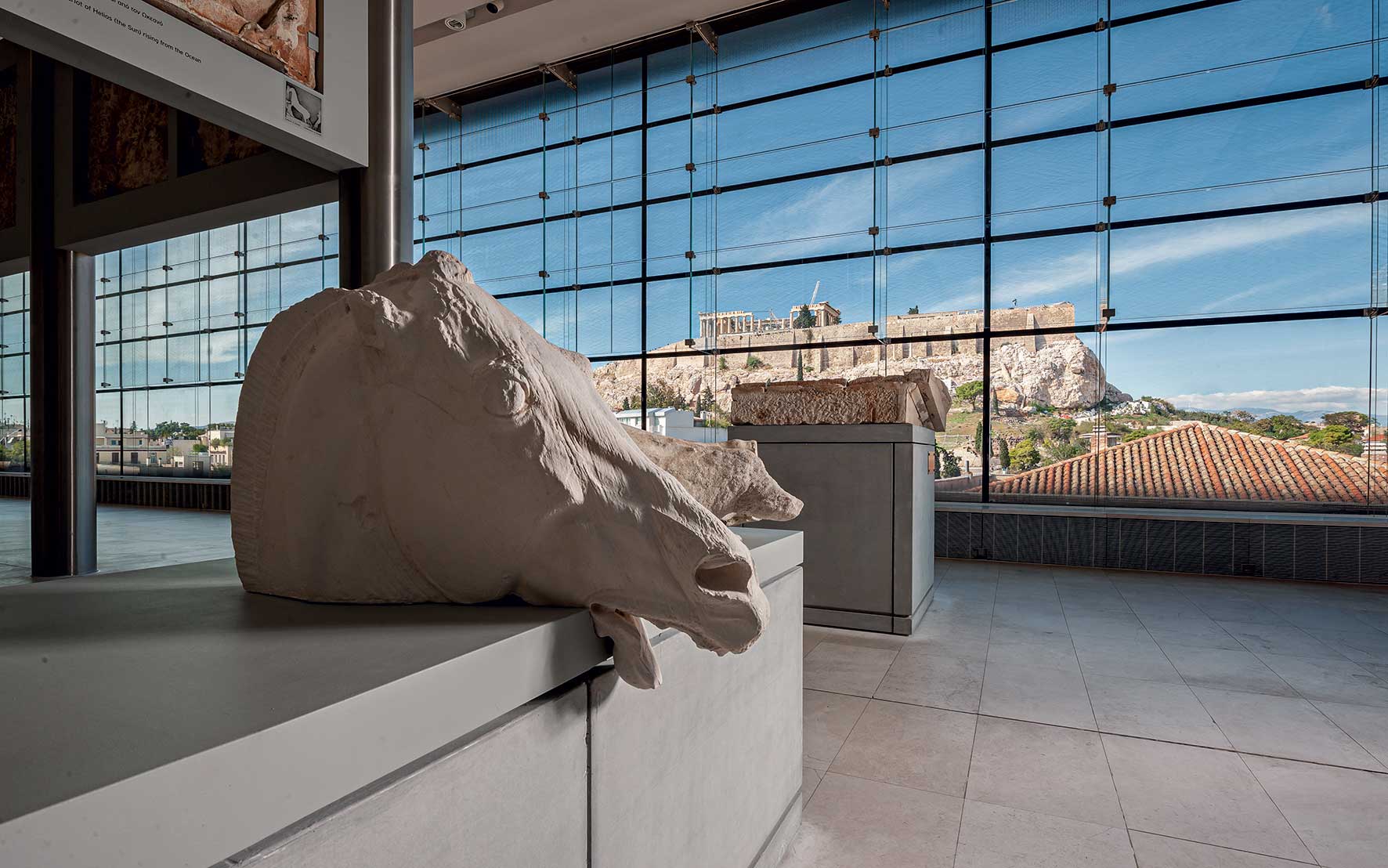

One of the surviving horses heads from the chariot of Selene, goddess of the moon, descending through the bottom of the east pediment. The Parthenon Gallery, on the third floor of the Acropolis Museum, is in direct alignment with the Parthenon atop the Sacred Rock.

© Giannis Giannelos

CT: The Parthenon is the perfect endpoint of architectural evolution and refinement that combines the styles of both orders, the Doric and the Ionic. In that regard, it is utterly unique. Even more extraordinary is that it was built by public decree, and the citizens controlled all the subsequent works and expenses. Records of this still exist. The sculptural decoration, traditional in the pediments and on the metopes, is revolutionary in the Ionic frieze, representing the Panathenaic Procession, wherein gods and people from all social classes participate together. The temple not only honors the goddess Athena but holds up a mirror to the inhabitants of the democratic city-state; this was the genius of Pheidias, fostered by the patronage of Pericles.

PC: They are unique in two main ways: just like in Renaissance Florence, mid-5th century democratic Athens could boast a unique concatenation or confluence of artistic talents – aesthetic, mathematical, constructional, theoretical – all of which was poured into the making of the Parthenon. Second, the Parthenon as a temple was unique in the ancient Greek world in several ways: the sheer quantity and finesse of its sculptural ornamentation – especially the 160-meter Ionic frieze in a basically Doric temple; all the architectural refinements that, for example, make subtly curved lines look straight; and, the fact, often overlooked that the temple had no dedicated altar. More important, politico-religiously, than the Parthenon was the next-door Erechtheion, the temple of the city patron goddess Athena Polias, which did have a dedicated altar, which the Parthenon had to share! The original was democratic because it was conceived, voted for, executed, and managed in entirely ancient democratic ways.

CT: They are all surviving parts of a giant puzzle that can never be pieced together again, but every existing part helps to reduce the lost ones and, as far as possible, complete the picture and restore its beauty – something that plaster casts could never do! For obvious reasons, the surviving sculptures cannot be reunited with the actual Parthenon building, which is one of the arguments for the refusal by the British Museum to return them. Still, at least they will be displayed in the sublime Parthenon Gallery on top of the Acropolis Museum, in direct visual contact with the monument atop the Sacred Rock, their natural environment. For people living in the vicinity of the Acropolis Museum today, these spectacular sculptures can be seen 24 hours a day, seven days a week! A majestic view, especially at night.

PC: Of course they should be returned to Greece. Imagine having bits of the Mona Lisa scattered between museums in France, Italy, Spain, Denmark, and England. That would be absurd! The Parthenon is a whole – of course, an incomplete and seriously damaged one, but still whole enough for all the extant parts to be reunified where they belong, in Athens, and in a dedicated museum, the Acropolis Museum, not in the appalling surroundings of Room 18 (the Duveen Gallery) at the British Museum. A keyword is “Acropolis.” The Parthenon was and is of the Acropolis, as well as [being] on it.

PC: None whatsoever. The Turks were not bent on turning the temple or its decorative sculptures into lime. Besides, why did so much of the monument survive despite nearly 400 years of Ottoman rule? Elgin’s mission was not to “save” the Marbles but to grab them – for himself. We know from contemporary sources that the local inhabitants of Athens at the time were distraught by their removal.

Statuary from the Parthenon's east pediment, on display in the Duveen Gallery at the British Museum. The UK Parliament purchased the sculptures "for the British nation" in 1816, but the move drew widespread condemnation, most notably from Lord Byron, who died in the Greek Revolution in 1824.

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

PC: Firstly, there is no evidence of a firman emanating from the Sultan – only an Italian translation of a summary of a particular type of firman granted by the Ottoman equivalent of the Foreign Secretary. That did not grant Elgin permission to do what he did. It merely allowed him and his men a free pass onto the Acropolis, a military garrison at the time, to copy some of the sculptures and architectural elements and remove some of the fragments lying around on the ground. To achieve that, his associate, the Reverend Philip Hunt, had to bribe several key officials.

CT: Turkish researchers Zeynep Aygen and Orhan Sakin, in a lecture at the Acropolis Museum in February 2019, described not finding any trace of the permission documents in the Ottoman archives. This is extraordinary when you consider that removing each fragment from the Acropolis would have required four copies of the firman. In theory, there should be a vast collection of documents in the archives, but it has yet to be found. Furthermore, why was the summary of the so-called firman Elgin presented to the British Parliamentary Committee in 1816 written in Italian and not in French, the language of international diplomacy of the time?

CT: We must keep the issue in the spotlight and apply continuous pressure upon public opinion by every means at our disposal. The various national committees must continue to host lectures, give interviews, write articles, present exhibitions, and so on, and we must assure the Greek authorities of our unending support until all the surviving parts of the sculptures are reunited in Athens. That is our goal.

PC: In terms of keeping the campaign in the public sphere, plans are quietly afoot to organize an “International Parthenon Day” next year, where every national committee can host a lecture or an open event to raise further awareness of the issue. Watch this space!

PC: We urge them to continue doing what they are doing and to demonstrate, by their votes, how out of step our politicians and the trustees of the British Museum have become. What’s new in former colonial-imperial countries like Britain, France, and Belgium is the recognition of the sins of our forebears in stealing the cultural property of others. To that end, the British Museum is finally beginning to realize that it needs to keep in step with the times and be a “post-colonial” institution.

The International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, including the British Committee, has worked tirelessly in support of the Greek authorities, applying pressure on the UK Parliament and the trustees of the British Museum.

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

PC: I don’t believe that the theft of the Benin Bronzes is directly comparable to the robbery by Elgin of the Parthenon sculptures, but the Benin repatriation campaign’s success has indirectly helped ours. Elgin did not send in troops to attack the Ottoman state. On the contrary, at the beginning of the 19th century, Britain and the Ottoman empire were on friendly terms – largely thanks to having a mutual enemy in Napoleon’s France – and Elgin was our Ambassador to the Sublime Porte of Constantinople (Istanbul). Nevertheless, Elgin’s attitude to Greece and Greek things was classically colonialist-imperialist and directly comparable to what happened in Benin in 1897.

CT: Western museums becoming aware of past wrongs during colonial rule are certainly helping our case, and growing public awareness and pressure is essential. One day, the British Museum must recognize this and change its mind.

PC: This was a cunning ploy devised jointly by James Cuno (Director of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2004-2011) and Neil MacGregor (Director of the British Museum, 2002-2015) when under pressure to return the Parthenon sculptures around the time of the opening of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens in 2009. The so-called “argument” that you can better appreciate the sculptures in the British Museum than in Athens was always totally useless and irrelevant.

CT: You do not need the Parthenon sculptures to prove you are a universal museum. There are other ways to do so, for example, by accepting the proposition of the Greek government for rotating exhibitions of artifacts that have never previously left Greece. Where can the Parthenon sculptures better be appreciated than in their place of birth, under the Attic sky?

© ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, 2012, PHOTO: SOCRATIS MAVROMATIS

CT: No “floodgates” would open. The case of the Parthenon sculptures is unique. Besides, every request for the return of a specific object from a museum collection must be thoroughly examined by a commission of international experts. Such commissions are establishing good working practices and laying the groundwork for open dialogue between museums and institutions. A recent example is the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium, working in close collaboration with representatives from the Democratic Republic of Congo, a former Belgian colony, to return looted items.

Regarding the Parthenon sculptures, the return of the “Fagan fragment” earlier this year from the Antonino Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo, Sicily, was a significant step forward in the campaign. The piece, depicting the right foot of Artemis from Block IV of the east frieze, was returned, following negotiations between the Greek Ministry of Culture and the Regional Government of Sicily, in exchange for a loan of two artifacts from the Acropolis Museum. This demonstrated a willingness on both sides to find an agreement, although it’s important to stress that the return of a fragment (“Figure 28” from the north frieze) from a collection at the University of Heidelberg in 2006 set things in motion. This was the first repatriation of a fragment from a museum outside of Greece.

The acropolis of Athens, above the historical Plaka neighborhood.

© Shutterstock

CT: As a former museum curator, I take issue with the idea of life-size copies or replicas taking the place of original artifacts. No curator will accept such a deal, and certainly not in the case of the Parthenon sculptures. Ultimately, they are fakes. As accurate as they may be, they lack authenticity and soul. You can undoubtedly use replicas for specific things – educational purposes, for example – but visitors will not show up to admire copies; they will feel deceived.

I’m sure that members of the other national committees will disagree with me but having a robot-carved copy of an artifact is not different, in this sense, from any other kind of replica. It’s not an individual creative act by a human being; it’s machine-made. What IDA did is undoubtedly a significant step forward in the evolution of copies, and it may open the door to other possibilities of research, but they can never replace the originals. I think it would be better to explore using Augmented Reality or Virtual Reality technologies (or a symbiosis of both) – that way, visitors to the British Museum could wear headsets and see digital copies on display and the originals can be returned to Athens.

PC: Yes, I totally agree. However brilliantly accurate any such copies are, they are aesthetically, culturally and historically dead. The work of IDA really started as a noble project to recreate the Palmyra Arch in Syria (3rd century AD), destroyed by Islamic State in 2015. Thanks to photographs and detailed architectural survey reports, we knew the exact dimensions of the monumental arch before it was damaged, so the building of a replica was really to prove a political point, namely that ISIS cannot completely obliterate Western culture.

The campaign for the return of the Parthenon sculptures is very different – a nearly 200-year-old campaign that began almost immediately after the birth of the Greek state in 1832. I think it’s important that we distance ourselves from the work of IDA. In his 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” art historian Walter Benjamin decried the loss of artistic authenticity; the existence of a mechanical copy diminishes the aesthetic value of the original work of art. Of course, new technology has fantastic uses, but not when it cuts across or even stops artistic creativity by individual human beings.

CT: That’s a difficult question. On the one hand, I’d say the current political and economic climate in the UK makes it difficult to see any light at the end of the tunnel. The British Museum keeps hinting at a “deal,” but nothing concrete has been laid on the table. More details may emerge in the spring. One thing is sure: nothing’s possible without changing the British Museum Act of 1963.

While I disagree with one day replacing the current display in the Duveen Gallery with replicas, we should be pushing for the Greek proposal of sending rotating exhibitions for that space. Every museum curator is under pressure to present new things to the public and, with ever-diminishing funds, it’s becoming impossible for museums to buy new items for their collections. If you establish close working partnerships with other museums – in this case, the Acropolis Museum – you open up the possibility of exchanging objects on long-term loans for temporary exhibitions. That, for me, is the solution. Send the Parthenon sculptures back to Athens and get a revolving door of other Greek antiquities to exhibit to the public. Besides, you don’t need the Parthenon sculptures to serve as “ambassadors” or “flagship” artifacts of ancient Greek culture in the British Museum. The Western sculpture galleries are already well stocked with other extraordinary objects.

PC: I entirely agree. Any so-called “deal” that is meaningful – i.e., that results in the actual reunification of the sculptures in Athens – will have to be made at the highest political level, that is to say by Acts of the UK Parliament. But the idea that any British government will put the issue of the sculptures that high in their legislative program any time soon is sheer fantasy. As you know, entry to public museums in the UK is free, which is, of course, a good thing, but that makes it very difficult for trustees to raise much-needed funds for regular upkeep and new exhibitions.

That said, the current chair of the British Museum, George Osborne, who served as the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016, is talking about a complete re-hang/reorganization of the Hellenic galleries at the British Museum, including the Duveen Gallery. This may entail more information in the display – i.e., putting the pieces in the correct order, as they are displayed in the Acropolis Museum, and offering more explanation about the gaps in the collection. This, of course, isn’t a solution to our problem, but it shows movement on the ground at the British Museum.

Another point is that George Osborne is very close to Lord Vaizey, chair of the newly launched Parthenon Project, which seeks to permanently relocate the sculptures to Athens. It will be interesting to see how that plays out. We in the national committees want to emphasize the positives. We’ve said that returning the sculptures to Athens could open new horizons for the British Museum regarding temporary loans and unique exhibits from Greece, which would be fantastic!

At the Athens English Comedy Club,...

A natural spa by the Athenian...

Only a short drive from Athens,...

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...