In ancient Greece, the roles of men and women were strictly segregated. If male citizens – and only men above a certain age could qualify as citizens – ran the assemblies and councils, and be directly involved in the affairs of their city-state (“polis”), a woman was expected to run the household (“oikos”). While it’s a bit of an oversimplification to say that a woman’s place was always in the home, it largely depended on which polis they were from, where they ranked in terms of social class, and what profession (if any) they practiced.

Precious little information about women in ancient Greece has survived in the written sources. What we do know is that there were significant differences between the lived experiences of women in Athens and Sparta. Women in Athens, for example, played no role in direct democracy, were unable to vote, own land, or inherit property; essentially, they had no legal “personhood.” Spartan women, on the other hand, received a more in-depth education, and could legally own and inherit property. Some even ran the estates of their husbands or other male relatives when they were away on military service.

© Caeciliusinhorto / Public domain

Childhood and education

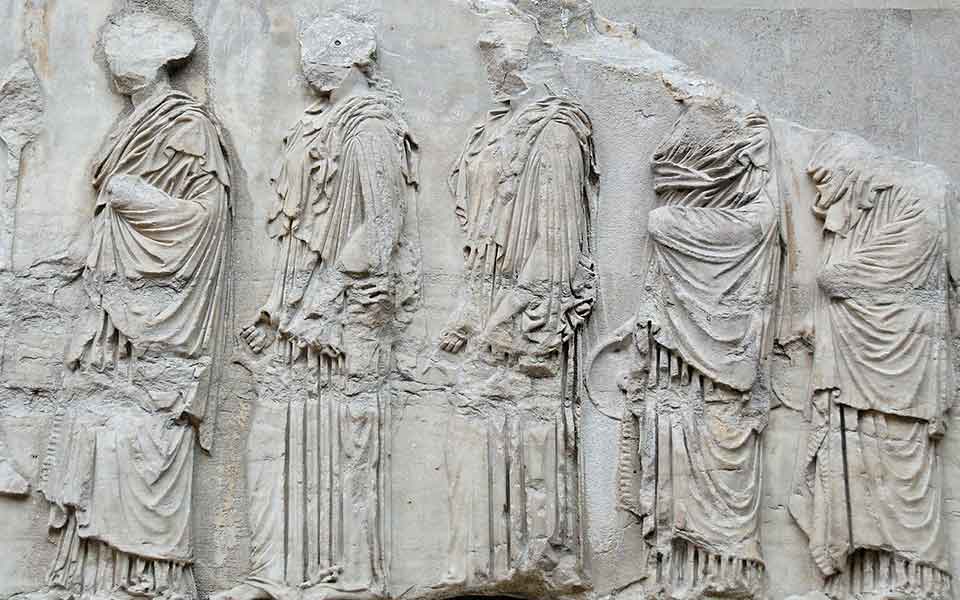

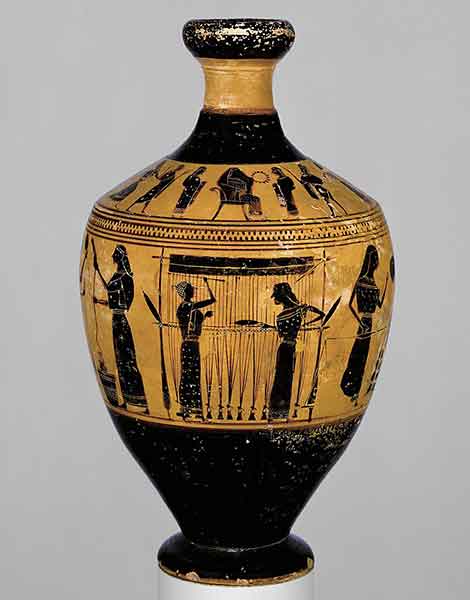

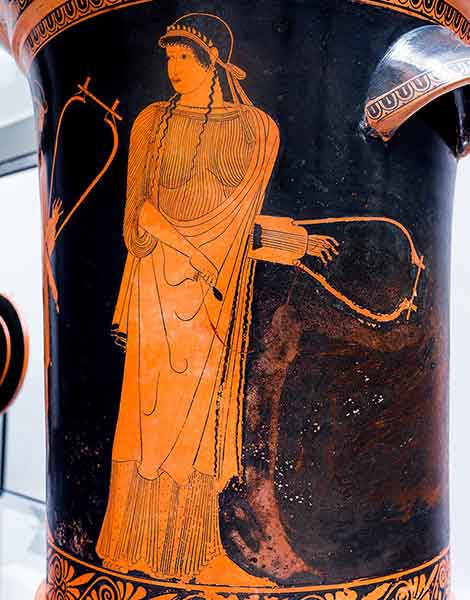

Most of our information for women in the Archaic (ca. 800-480 BC) and Classical periods (480-323 BC) comes from Athens, primarily from Attic tragedy, comedy, and oratory. Artwork, especially vase painting, provides another important source of information on appearance and day-to-day activities.

Infant mortality was incredibly high in Classical Athens, with as much as 25 percent of children dying at birth or soon after. It is known that families celebrated coming-of-age rituals at five, seven, and 40 days after birth. If they survived, Athenian children were formally named on the tenth day (the “dekate”).

Young girls spent most of their time in the “gynaikon,” the women’s quarters, located on the upper floor of the house. It was here that mothers, female servants, and wet nurses raised the children and engaged in household chores, including spinning thread and weaving. Athenian girls were educated at home by their mothers, who taught them the essential domestic skills, including cooking, embroidering, and, in the case of wealthy households, how to manage slaves. Only the very wealthy learned how to read and write.

© Attributed to the Class of Hamburg 1917.477 - Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011) / Public domain

Girls who lived in Sparta had much more freedom than their counterparts in Athens. Spartan girls were educated at home but took part in a program of athletics and gymnastics, in preparation for marriage and motherhood; healthy mothers, healthy children. As Sparta was a highly militarized state (all male citizens – “Spartiates” – were full-time soldiers), women enjoyed considerable status as the mothers of Spartan warriors. They also learned music, singing, and dancing.

In most city-states, it’s likely that girls (“kore” – maidens) rarely left the gynaikon until they reached marrying age, typically around 14 or 15 (20 in Sparta). There were special occasions when girls were allowed to attend religious festivals, and young women in Athens could perform certain domestic tasks outside of the house, inlcuding fetching water from the local public fountain.

© Marlay Painter - Jastrow (2007) / Public domain

Marriage and motherhood

Women in ancient Greece were expected to get married and rear children; a task that was regarded as their social responsibility. Marriages were usually arranged between the parents of the bride and groom, a betrothal, and depended on the girl’s father or guardian giving formal permission to a suitable male partner. Girls in Classical Athens were simply passed from the protection of their father to that of their husband. The consummation of marriage signalled the end of a young woman’s status as a kore. She was now classified as a “nymphe” (bride).

While girls married in their mid-teens, men were usually in their late 20s or early 30s. In the case of Sparta, marriage was strictly enforced by the ancient laws of Lycurgus (a semi-mythological statesman of the late 9th century BC), which recognized the vital importance of every citizen family raising future warriors to serve the state. Spartan women rarely married before the age of 20. On the night of her wedding, the bride would have her hair cut short and be dressed as a man. After which, she was left alone in a darkened room, where she would be “ritually captured” by her groom.

In Athens, marriage had to be between citizen families (i.e., of free status). Following the city-state’s strict citizenships laws, only children (sons) of such unions would be considered legitimate Athenian citizens when they came of age. Furthermore, “the richer you were, broadly speaking, the more confined you were,” according to classicist Paul Cartledge. While women were in charge of the day-to-day running of the household, in the eyes of the law, they were under the complete authority of their husbands. And, as women in lower class families regularly went outside the house to draw water or visit the marketplace, the wives of wealthy Athenians would not have ventured out in public unchaperoned or interacted with men who were not relatives.

© Public domain

© Public domain

Other roles

While participation in most religious festivals in ancient Greece were reserved for male-citizens, a number were set aside exclusively for women, including the Thesmophoria, a three-day celebration of the goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone. According to ancient sources, the festival took place in the fall, at a time when farmers were planting crops of wheat, barley and legumes for the winter. The rituals, associated with fertility, ensured divine protection for the land in the hope of a bountiful harvest.

In Athens, unmarried women from aristocratic backgrounds were eligible to serve as “hiereiai” (priestesses) or custodians for many of the city’s religious cults. The most senior religious office – high priestess of Athena Polias – was reserved for a woman, and would have afforded a significant degree of influence and prestige.

Slaves and lower class women would have worked in shops and market stalls, while others would have worked as prostitutes, a role for which historians have the most information. Two groups of sex workers existed in ancient Greece: “pornai” and “hetairai.” The former (from where we derive the word “pornography”) were common prostitutes who worked in brothels and were expected to serve men from all social classes. Hetairai, on the other hand, were high class companions, similar to Geisha women in Japanese culture. Many of these women would have known how to read and write, play musical instruments and engage in conversation with men at “symposia” – infamous all-male drinking parties. As such, some would have been schooled in literature and the arts. Some scholars have suggested these women were not courtesans at all, but elite women who participated in luxury culture.

A famous example of a hetaira was Phryne (ca. 371-316 BC), originally from Thespiae in Boeotia. Active in Athens, she bared her breasts to the (all-male) jury during her trial for impiety. Awe-stuck by her beauty, she was immediately acquitted.

© Public domain

© Jastrow (2006) / Public domain

Despite the many restrictions women faced in ancient Greek society, a number of individuals were widely celebrated for their extraordinary achievements. One of the most famous was Sappho (ca. 630-570 BC), born to a wealthy, perhaps even aristocratic family in Mytilene or Eresos, on the island of Lesvos. Famous for her lyric poetry (written to be sung while accompanied by music), she described love, passion and sexuality, often between women. One of ancient Greece’s most celebrated poets, Plato dubbed her the “Tenth Muse.” Fragments of her work were discovered by British archaeologists Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, in the late 19th and early 20th century (the “Oxyrhynchus Papyri”).

Another famous woman was Aspasia (ca. 470-after 428 BC), the common law wife of Pericles, politician and general during the “Golden Age of Athens.” Born in Miletus, on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, she moved to Athens and worked as a hetaira, where she began a relationship with Pericles, to whom she later bore a son, Pericles the Younger. Little is known of her life, but ancient sources suggest she possessed a sharp intellect and exercised a degree of influence over Pericles. Comedy playwright Aristophanes quipped about her role as a prostitute and brothel-keeper in “Archarnians.”

While it’s fair to say that ancient Greek society revolved around men, there are known cases of strong, independent and self-reliant women who rose to positions of influence. In ancient Greek religion, powerful goddesses, including Athena, Aphrodite and Artemis, were worshipped, admired and feared in equal measure, and strong female characters in literature were often represented a direct threat to the established patriarchal order.