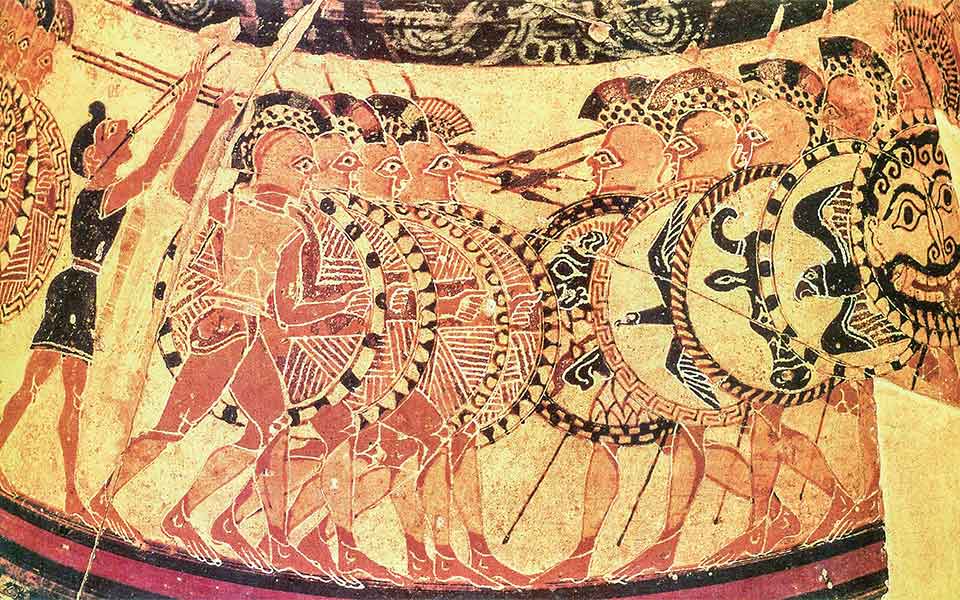

Between July and late September 480 BC, as the heavily outnumbered Greeks crashed headlong into the full might of the Persian empire at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and Salamis, another battle raged in a faraway Greek colony on the island of Sicily.

The Battle of Himera, one of the most important battles of the Sicilian (or Greco-Punic) Wars (580-265 BC), was a matter of survival for the westernmost Greek colony in northern Sicily, founded by Dorian and Ionian Greeks around 468 BC. Fought between the Punic people (western Phoenicians) of ancient Carthage, led by Hamilcar I, and a combined army of the Sicilian Greek colonies, Greek victory derailed Carthaginian ambitions to dominate the island for another two generations.

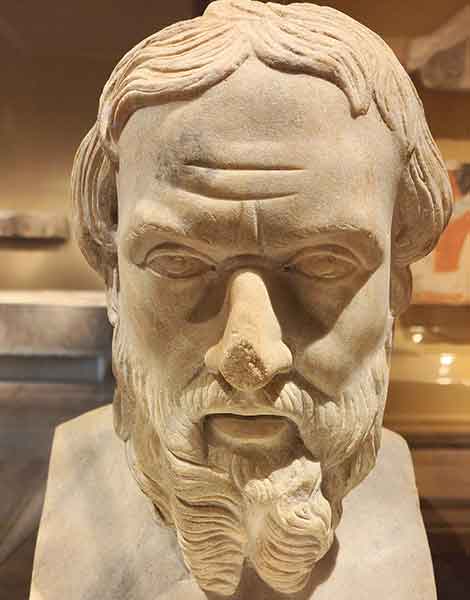

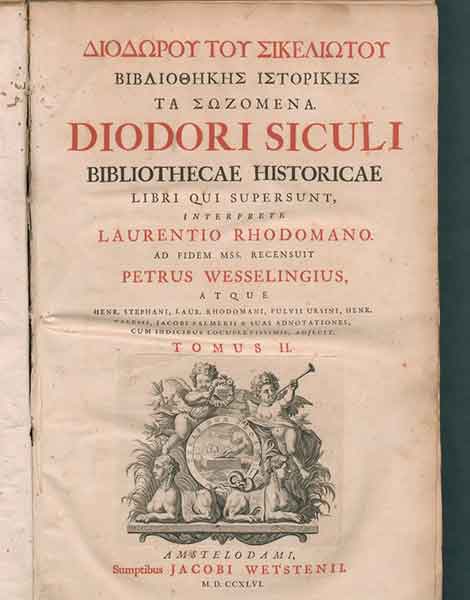

According to the Greek historian Diodurus Siculus, who was writing more than 300 years after the events, heavily armored citizen-soldiers (“hoplites”) from other Sicilian city states rushed to the aid of the Himerans, including Agrigento and Syracuse. “There followed a great slaughter of the enemy,” he wrote.

Both Diodorus and the earlier historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, praised the victory as an example of what made Greek culture great; that Greeks could unite in the face of foreign aggression. But neither author made mention of one key fact: that many of the soldiers who came to Himera’s aid in the summer-early fall of 480 BC weren’t even Greek.

Spears for Hire

A recent study that analyzed the ancient DNA of human remains from mass graves in the cemeteries of Himera made the startling discovery. Published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the authors presented evidence of the genetic origins of 54 corpses, unearthed from a communal grave of 5th century BC soldiers in the recently excavated west necropolis. Chemical analysis of the bones found that many of the soldiers, otherwise healthy adult men between 18 and 50, originally came from northern Europe, the Steppe, and the Caucasus.

This latest finding further supports research that was published last year by Katherine Reinberger and colleagues, who analyzed the remains of 62 fallen warriors from mass graves near the site of the ancient battlefield, unearthed in 2007 and 2008. Reinberger, a bioarchaeologist from the University of Georgia, concluded that two-thirds who those fought in the defense of Himera in 480 BC may have come from abroad. Combined, both studies highlight an under-appreciated aspect of ancient Greek warfare: the role of foreign mercenaries from faraway places.

But why did the ancient authors downplay the presence of foreign fighters in the life-or-death defense of Himera?

Speaking to the New York Times, David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard University and co-author of the most recent study, believes that “Greeks minimized a role for mercenaries, potentially because they wanted to project an image of their homelands being defended by heroic Greek armies of citizens and the armored spearmen known as hoplites.” Armies that contained large numbers of spears for hire undermined this image of the heroic ideal.

“Being a wage earner had some negative connotations – avarice, corruption, shifting allegiance, the downfall of civilized society,” adds Laurie Reitsema, an anthropologist at the University of Georgia and another co-author of the latest study. “In this light, it is unsurprising if ancient authors would choose to embellish the Greeks for Greeks aspect of the battles, rather than admitting they had to pay for it.”

Mass Graves

The western necropolis at Himera was discovered in 2009, during major construction works for the rail line connecting Palermo and Messina. During the excavations, archaeologists unearthed more than 10,000 burials, dating from the 8th to 5th century BC. Many were found to be individual burials, adorned with an assortment of grave goods. Large communal graves, on the other hand, containing the remains of adult men with evidence of violent trauma, were more likely to contain foreign mercenaries than local citizen-soldiers.

“Most likely, mercenaries would not have been known to the people cleaning up the battlefield and burying the casualties,” Reitsema continued. “As a result, mercenaries would have been more likely than citizen-soldiers to wind up in anonymous mass graves and become archaeologically invisible, or less visible.”

The mid-first millennium BC trade networks that extended across the Mediterranean and the far reaches of Europe brought Greeks into contact with people from a wide range of populations. The use of Greek mercenaries in ancient warfare was well known – Herodotus’ account of the “bronze men from the sea” refers to the Ionian Greeks who fought in the military campaigns of pharaoh Psamtik I against the Assyrians in the 7th century BC – but the presence of foreign mercenaries in Greek armies is largely absent from the historical texts.

Greek forces were victorious in 480 BC, both in the defense of Greece against the Persians, and in the defense of the Greek Sicilian colony of Himera. But, 70 years later, in 409 BC, the Carthaginians returned, this time under the leadership of Hamilcar’s grandson, Hamilcar Mago. In the second battle, far fewer came to the aid of the Himerians, both foreign mercenaries and fellow Greeks from the neighboring city-states, and the city was razed to the ground. It seems, therefore, that the role of the foreign mercenaries in the first battle was pivotal and helped turn the tide of the war.

Perhaps one of the biggest surprises from this study has been the enormous distances over which foreign mercenaries traveled to get to Sicily, some as far as modern-day Ukraine in the east and the Baltic region of Latvia in the north. “We think of warfare as causing or deepening divisions between people,” said Britney Kyle, an anthropologist at the University of Northern Colorado and another co-author of the study. “So, it is fascinating to think of war as something that could bring people together.”