Any of us who tried to explore the possibility of surfing on the Greek coastline during the ’80s and ’90s, hit a wall: everything around us seemed to give the same message, and the message was disheartening. Especially if you happened to live in the center of Athens, even the mere thought of sliding on moving waves (the way we’d seen people do in places like California or Australia in movies, tv shows or magazines) seemed rather exotic.

In the narrow streets of central Athenian districts like Kypseli or Exarcheia, sun-and-sand rock’n’roll songs like the Ramones’ “Rockaway Beach” were the sound of the sea itself, but, even if the coast was just a half-hour drive away, amidst the urban cement and the traffic fumes, the freedom of surfing in oceanic waves felt like a pipe dream.

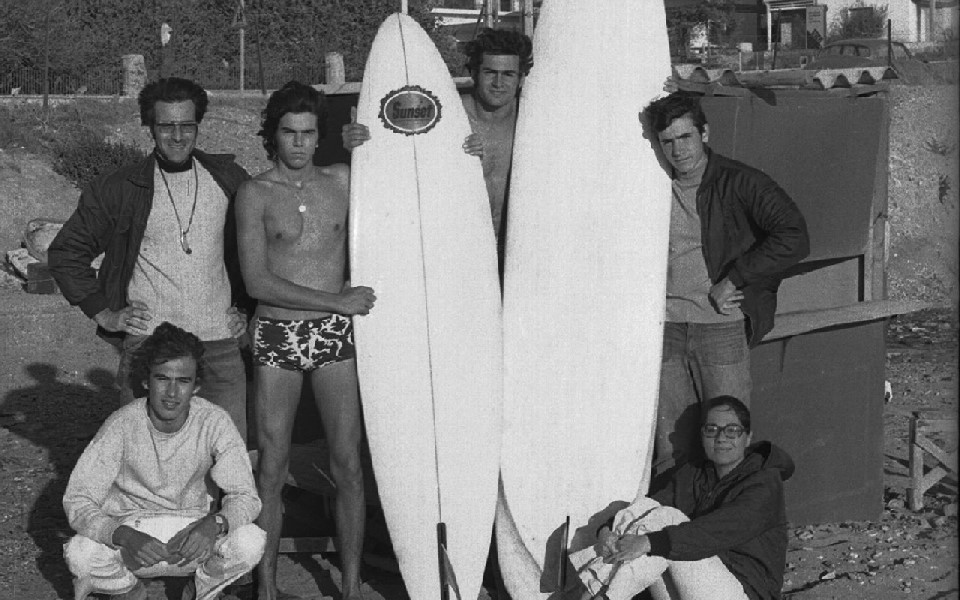

© Konstantinos Pikros

At the same time, the sport of windsurfing had already been extremely popular all around Greece, and in a windy country surrounded by sea, that seemed natural. But, when you asked around about the potential of surfing, everyone was quick to give the typical answer: “There are no surfing waves in Greece, you’re better off trying to windsurf.” Indeed, everyone seemed to have a windsurfing board, but no one had a board without a sail.

But, could it really be possible that, in a country of almost fourteen thousand kilometers of coastline, no one had ever surfed? The question lingered on through the years, as popular culture went on teasing us, reminding us of the “forbidden fruit”: Beverly Hill 90210’s Dylan would take Brenda on a surfing trip down to Mexico, Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayzey were turning the sport mainstream by starring in “Point Break” and future world champion Kelly Slater would appear in “Baywatch” alongside Pam Anderson, often grabbing his board and riding waves. At the same time, the “cool” clothing of the era (brands like Stüssy or Ocean Pacific) were teeming with surf iconography, while teenage magazines would often choose stereotypical surf scenes for their colorful covers.

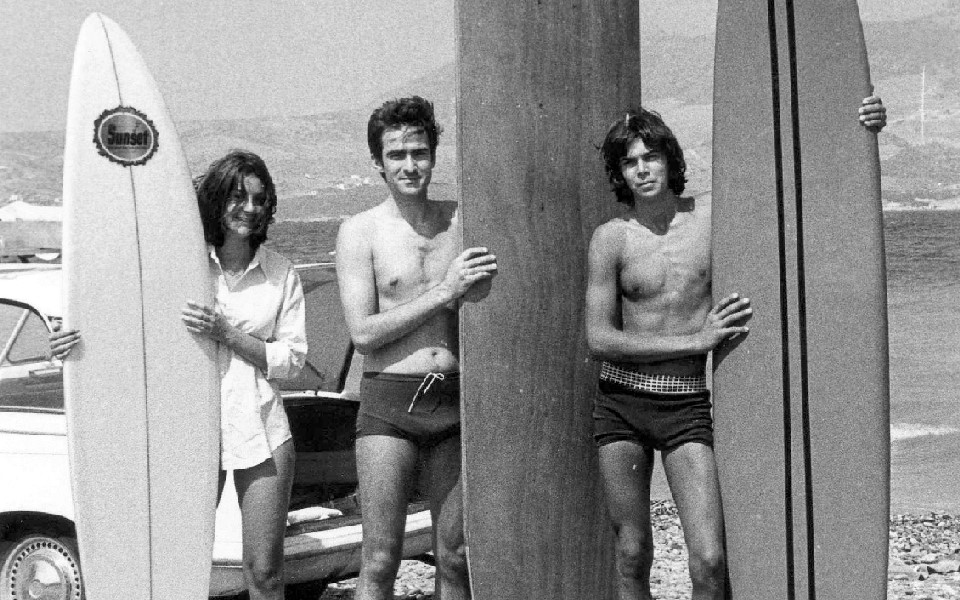

© Konstantinos Pikros

But all these ideal, fleeting pictures of a summer under the sun and next to the surf, remained a fantasy. Even at the house parties or bars we’d go to, the DJ would play surfin’ tunes by bands like The Trashmen or Radio Birdman or the Beach Boys, and surfing was literally everywhere in popular culture, but still nowhere to be found in real life.

There was a group of Athenians, though, that dreamed of surfing before us Gen-xers. In order to find them, we have to go to the coast of Kalamaki, just off central Athens, and travel in time back to the ’70s. There we can find Konstantinos Pikros, an engineer propelled by a unique sense of inventiveness and an adventurous spirit. He was the one who brought surfing for the first time – albeit, briefly – on the coasts of Attica, and he left back a short but comprehensive written account called “Wavereding 1970” to tell us the story.

© Maria Boukaouri

Pikros and his small group of friends experimented with constructing their own custom surfboards, they mounted them up on the roof of their car and set out looking for waves on the coasts around Athens. They gave their team a name, designed a logo and printed it on T-shirts, and, in a fantastically self-sarcastic, joyous and romantic mood, actually caught small waves on the south and eastern coast of Attica and saw in it all the beauty of “a sport for free-spirited minimalists,” as Pikros so beautifully states in his memoirs.

It only felt natural that the next generation of Athenian surfers, who made their appearance a whole twenty-something years later in the mid-late 90s, shared the same sense of humor with him. This new group of Athenian waveriders were ex-windsurfers and snowboarders.

© Maria Boukaouri

As Jack o’Neil, the American inventor of the wetsuit, famously said sometime in the ’90s, “snow is only frozen water” – and it was only natural for the Athenian snowboarders (who have been training for the whole of the ’90s on the slopes of mounts Parnassus and Kalavryta, only a three-hour drive away from the capital), to seek out the potential of the “mother sport” on nearby coasts. They had already felt the joy of surfing on packs of fresh powder on the mountainside, but they were craving to experience the real thing. And, if Constantine Pikros was the leader of the pack in the southern suburbs in the 70s, Dimitris Liossis, a London-educated painter, was the main man in the northern suburbs in the 90s. He was covered with tattoos long before it was a trend, he used to paint his hair green and was a terrific graffiti artist and airbrush expert.

Liossis was a talented eccentric who could be an instant inspiration to anyone seeing him pull a huge “backside air” trick on his snowboard. He enriched his riding with a flamboyant sense of artistic creativity and made all of us realize that technical ability is nothing if not accompanied by an authentic, unique, personal sense of style. Most importantly, he convincingly made the case that these new activities were not some sort of subculture or underground activity for kids, but a new breed of sports with a whole set of cultural and athletic values of their own. Three decades later, skateboarding, snowboarding and surfing are Olympic sports.

Of course, we knew back then (as we very well know it today) that Athens will never become Sydney, Honolulu or San Sebastian. Our waves are not generated by vast expanses of ocean, and swell is not consistent. But still, we counted on the dramatic landscape, the sun of Attica, the clean blue waters, and, of course, the thrill of the exploration, the excitement of “the first time.”

We soon found surf on both the south-facing and east-facing coasts of Attica, but it wasn’t long before we set off chasing surfable waves in the rest of the country. In places like Parga or Crete we found there was already a small, local surf scene, and then there were new spots we established, spots that very quickly became very popular (like the islands of Tinos and Ikaria or the whole of the west coast of the Peloponnese). And, in the last two decades, the bay of Vouliagmeni, on the south coast of Athens, has been the Athenian surfing spot par excellence.

We’ve contacted a few of the local protagonists and pioneers, asking for a few words on their surfing experience there, and the first who came to mind was Pavlos Cheiladakis, one of the local pioneers. Owner of the windsurfing/surfing school “Yasurfaki” on the beach of Varkiza, he caught his first wave at some point in the early 90s, by pulling the sail off his windsurf. “I can never forget how it felt,” he says, bringing to mind the motto of “Slick Bitch,” the first surf shop in the area: “Only a surfer knows the feeling.”

© Spyros Plesiotis

© Dimitris Karaiskos

Simos Varias, another local surfing pioneer, remembers: “Slick Bitch brought surfing culture to Athens straight from the U.S., when its owner bought around fifty boards by the Hawaiian brand “Town and Country” and put them for sale at his shop. They were sold very fast, and these boards really served as educational tools for a whole bunch of new surfers. But there was an Italian guy, Lorenzo, who was the real catalyst.”

Pavlos Cheiladakis agrees: “He was a wizard, a sage! He helped me learn how to surf – and he inspired so many others, just by the way he surfed. This guy really wanted to share his knowledge, and he did it with generosity.” Varias adds: “We were total rookies back then, and he opened our eyes.”

Lorenzo Pellegrini, the Italian engineer who lived briefly in Greece, working on the construction of the Athens Metro, rightfully took his place in the local surfing history, alongside Konstantinos Pikros and Dimitris Liossis. He came and left quietly, but left a treasure of surfing knowledge for us. Two decades after Lorenzo, there’s a whole new, third generation of local riders, and in the swarms of locals trying to catch a wave in Vouliagmeni today, we find a colorful mix of younger and older talent – and quite a few girls.

One of the prominent female figures of the local scene is physical education instructor Elisavet Mavraki. Her words are full of female power: “All these qualities I activate while surfing, I try to transfer to my real life – adaptivity, readiness, strength, patience, perseverance. This is what this sport taught me, and this is what it can teach young people. It can heal our soul, when we synchronize it with our bodies. But if we don’t, we’ll miss out on the wave. And the wave, one can say, is life itself,” she passionately says.

Vassilis Karageorgiou, one other local pioneer, tells us similar things when he talks about how firmly believes his three young children – all under ten years old – are getting the best of education by the sea itself. One of his sons, Nicholas, a bright new talent, exclaims: “My dream is to surf for the whole of my life!” Watching him catch waves, you know he will, and you get the same feeling while talking to Nick Kouzis and George Asimakopoulos, two of the new generation of surfing, both in their 20s. Nick, in a mature tone that seems very advanced for his 23 years of age, tell us of how surfing has set his mind in a mode of self-improvement, and how it’s the hunt for the waves that he finds more important than the wave-riding itself: “Waves can make you fall in love and respect the power of nature, but searching for them will help you love yourself and the small things in life,” he says. “The sense of relaxation I have after a session is something that I know I’ll be chasing for the rest of my life,” George adds. These young surfers have a longing to surf that will probably last for the whole of their lives, and they already know that surfing makes their lives better.

© Vasilis Karageorgiou

It all seems that surfing in Athens is no longer an exotic dream, but more like an overcrowded reality. Once there were a dozen or so surfers out, but today, on a typical winter swell in Vouliagmeni, you can find a crowd of more than a hundred.

Efi Vraka, one of the most technical women surfers in Athens, remembers the times when back in the start of 2000, she would skip classes at school to go down to her home spot and catch waves. “It’s sad watching some of the surfers today, how they react in the water, how they have no respect for others,” she says. “There are rules in surfing, as in everything in life – and they should do proper lessons with a proper instructor before trying to surf.”

Maria Zaharopoulou, one of the first female-surfers and the first surf instructor in the country, adds to that thought: “Sure, Vouliagmeni is overcrowded and this is disagreeable for everybody, but it’s not just a local phenomenon – it’s global. We just need some time to get accustomed to the sport and its culture – and perhaps we also need a wave pool!” Efi Vraka agrees: “The sport is becoming more and more popular the world over, and this is why wave pools are the future,” she says.

© Dimitris Karaiskos

Hoping for such an investment in the near future, for the time being we only have our waters, our local surfing spots, where we, the second generation of Athenian surfers, see an utopia of the past become a maturing reality of the present – and the future. Along with the amazing youngsters of today, we form a noisy bunch of two and three generations of Athenian wave-riders that are craving for the adrenaline rush of sliding on the back of a rolling wave, that unforgettable feeling “that only a surfer knows.”

Attica surfing is here, full with shops and local brands and a bunch of schools and instructors to choose from. And even if the waves are not always perfect and often are overcrowded, at the end of the day, as Pavlos Cheiladakis says paraphrasing the old cliché: “The best surfer is the one with the bigger smile.”