Just about everyone has heard of the pyramids of Egypt – the most famous of all being the 4,600-year-old Great Pyramid of Giza just outside Cairo, the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Even those with a passing interest in history and archaeology will have come across the early mud-brick pyramids (“ziggurats”) of Mesopotamia, the massive stepped-pyramids of the various Mesoamerican cultures (the Maya and Aztecs, for example), and the ornate pyramidal-shaped temples of the Khmer empire of Cambodia. But when we think of these enigmatic monuments, ancient Greece does not usually spring to mind.

For thousands of years, pyramids were the largest human-made structures on earth. With their basic triangular shape – the majority of the weight closer to the ground, working up to a “pyramidion” (cap stone) at the apex – enabled ancient engineers and architects to build large, stable monumental structures.

© KennyOMG

© Pedro Marcano

© thomaswanhoff

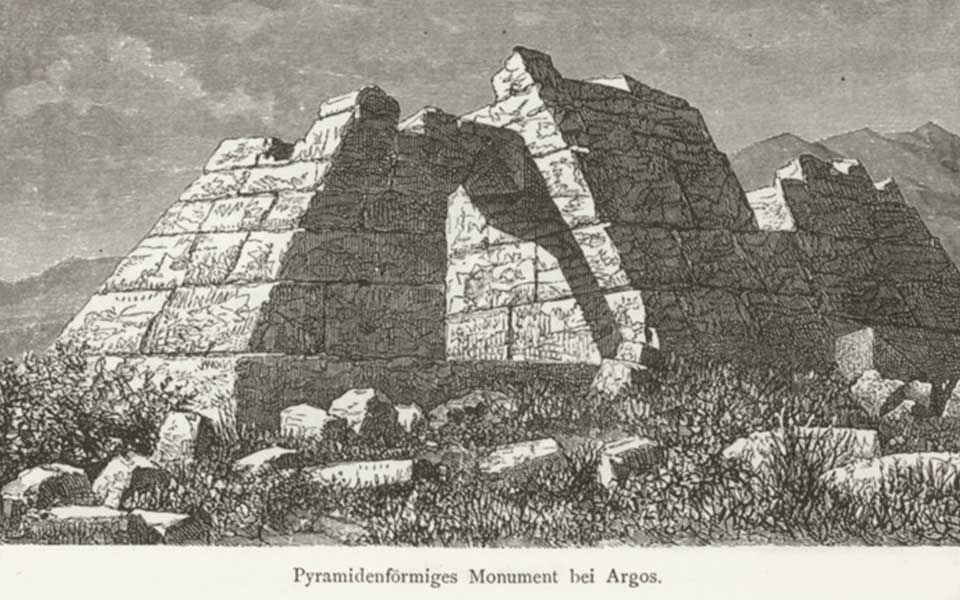

While the aforementioned pyramids are much larger in size (and infinitely more iconic), several truncated pyramidal-shaped structures in the Argolid region of the eastern Peloponnese have got archaeologists scratching their heads, mulling over theories concerning their origins and function.

The best preserved of these is the so-called the Pyramid of Hellinikon, located on the southeastern edge of the plain of Argos. Made of large blocks from locally-sourced grey limestone, the structure rises a modest 3.5 meters from ground level and surrounds a rectangular building with dimensions 7.03 meters by 9.07 meters. By comparison, the Great Pyramid of Giza, originally built as a tomb for the Fourth Dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu, had an initial height of 146.5 meters!

Another extant “pyramid” is in the nearby village of Ligourio, a stone’s throw from the ancient Sanctuary of Epidaurus, while others have been identified at Kambia, also in the Argolid, and Viglafia in Laconia.

While these conspicuous structures have garnered a good deal of interest among modern scholars, precious little is known about them. To make matters even more challenging, only one ancient writer describes a single pyramidal-shaped monument in the Argolid – the 2nd century AD Greek geographer, Pausanias. In his brief description, he links the building to the legendary struggle for the throne of ancient Argos:

“On the way from Argos to Epidaurus there is on the right a building made very like a pyramid, and on it in relief are wrought shields of the Argive shape. Here took place a fight for the throne between Proetus and Acrisius; the contest, they say, ended in a draw, and a reconciliation resulted afterwards, as neither could gain a decisive victory. The story is that they and their hosts were armed with shields, which were first used in this battle. For those that fell on either side was built here a common tomb, as they were fellow citizens and kinsmen.” (Pausanias, Description of Greece 2:25).

© Amand Schweiger von Lerchenfeld in "Griechenland in Wort und Bild, Eine Schilderung des hellenischen Konigreiches," Leipzig, Heinrich Schmidt & Carl Günther, 1887

An Archaeological Mystery

First excavated by the German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand at the beginning of the 20th century, the pyramid at Hellenikon became the subject of a later, more intensive study by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens in 1937.

In his 1938 report, site director L. Lord concluded that the pyramidal structures at both Hellenikon and Ligourio may have functioned as fortified garrisons, used to control or oversee the surrounding countryside. Excavated pottery inside the pyramid at Hellenikon, inlcuding a large storage jar (pithos), was provisionally dated to the Early Bronze Age (Protohelladic II period, 2800–2500 BC), but other ceramic items were found to be much later in age. Among these were oil lamps and various domestic wares dating to the late Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods.

In a later study in 1990s by Greek archaeologists Ioannis Liritzis and Adamantios Sampson and a team from the Archaeological Museum of Nafplio discovered that the astronomical orientation of the long entrance corridor of the Hellenikon pyramid would have aligned to the rise of Orion’s belt c. 2400–2000 BC. This extraordinary revelation, backed up with thermoluminescence dating of the rock surfaces of the actual building to the same period, place these remarkable structures in the same timeframe as the great pyramids of Egypt.

The “Egyptian connection” nevertheless remains highly controversial, with several archaeologists criticizing the research methods and dating techniques. In response, Sampson has argued that the pyramid stood on an earlier foundation of a 4th-3rd millennium BC Protohelladic building, but the later structure dates to the Classical period. As to its function, the jury is still out.

Over the years, archaeologists have suggested a range of theories, from guard houses for Egyptian mercenaries in Bronze Age Greece to tombs that mimicked ancient Egyptian burials. Other, more conservative theories include a sturdy, well-built storage place for agricultural produce, or as a refuge for people in times of local conflict.

In a recent twist, a team of archaeologists from Cambridge University discovered a pyramid-shaped promontory on the Cycladic island of Keros, deliberately carved into terraces and covered with 1,000 tonnes of specially imported gleaming white marble. Under the terraces of the Dhaskalio promontory were found a complex network of drainage tunnels and evidence of metalworking. The 4,500 year-old site would have resembled a vast stepped pyramid rising out of the Aegean sea.

Constructed 1,000 years before the famous Minoan palace of Knossos in Crete, the giant “pyramid” on Keros, according to project directors Colin Renfrew and Michael Boyd, was a densely populated settlement that bears all the hallmarks of the beginnings of complex urban planning.

Whether or not there were any connections to the so-called “Pyramids of Argolis” on the mainland remains an open question, but it seems the iconic pyramid shape also found its uses in the early Greek world.