A large, four-wheeled chariot, almost perfectly preserved in volcanic ash following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, was found earlier this year during excavations just north of Pompeii, in the portico of a wealthy suburban villa in Civita Giuliana.

Engineered from iron and wood, and adorned with “almost intact” ropes and floral decorations, the ornate chariot, found opposite the remains of three horses, has been described by the Italian culture ministry as “a unique find, without any precedent in Italy”.

This remarkable discovery bears all the hallmarks of a ceremonial chariot used in civil or religious processions, similar to the well-preserved remains of five carriages found at the Mikri Doxipara-Zoni tumulus (burial mound) in northeast Greece in 2002.

© Archaeological Park of Pompeii - http://pompeiisites.org/en/comunicati/the-four-wheeled-processional-chariot-the-last-discovery-of-pompeii/

© Archaeological Park of Pompeii - http://pompeiisites.org/en/comunicati/the-four-wheeled-processional-chariot-the-last-discovery-of-pompeii/

Ceremonial carriages in Thrace

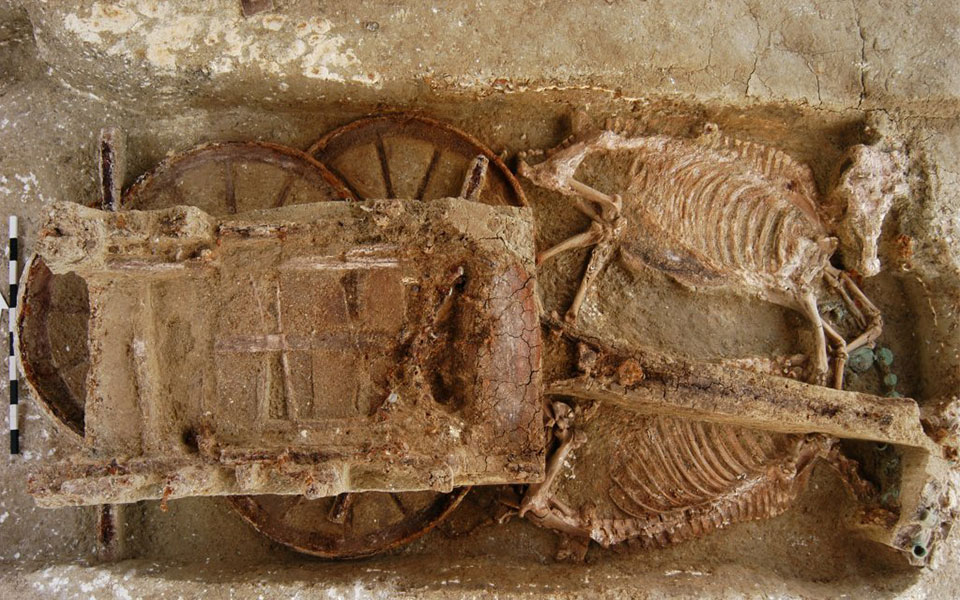

Inside the tumulus, archaeologists from the 19th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Thrace, under the direction of Diamantis Triandafillos, then director of the Ephorate, and Domna Terzopoulou, discovered five ornate carriages, buried alongside their horses, and the cremated remains of three men and one woman.

The large conical-shaped burial mound, filled with rich grave goods dating to the beginning of the 2nd century AD, belonged to a wealthy landowning family in Roman Thrace.

Located close to the ancient road leading from Hadrianopolis (Edirne, Turkey) to Philippoupolis (modern-day Plovdiv in Bulgaria), and west of the River Evros, the mound would have been a prominent feature in the landscape, built up over time to commemorate the dead.

© Ministry of Culture and Sports

The five carriages were buried, in some cases with their horses still harnessed, in shallow pits cut into the natural rock. Their iron frames, axles, and wheels, as well as decorative parts have all been well preserved.

In one case, bronze plates with silver discs depicting horses and riders in relief were found on an ornate trapezoidal backboard. Traces of leather harnesses and fragments of wood also survived.

The burial of the dead with their horses and carriages was common practice in many parts of the ancient Greco-Roman world, often recounted in contemporary literature and iconography. But while many horse burials have been discovered, finds of near-complete four-wheeled carriages are incredibly rare. The examples found at Mikri Doxipara-Zoni in 2002 were the first of their kind in Greece.

© Ministry of Culture and Sports

Marriages and deaths. Similar carriages, different contexts

The Thracians were variously described by ancient writers as “horse herding”, “horse loving”, and “horse breeding” people. They employed horses for agricultural work, hunting, and transportation, and, from the 1st century AD onwards, supplied the Roman army with large numbers of horses and skilled riders.

Thracian-bred horses also took part in chariot races. As the Roman empire expanded in the first two centuries AD, horses were bred in ever larger numbers to keep pace with the increasing number of military campaigns on the frontiers. Corresponding designs of chariot, carriage, and transport wagon were developed for a range of different purposes, both functional and ceremonial.

The carriages in Italy and Thrace bear striking similarities in both decoration and design, and were used for ceremonial purposes, albeit in very different contexts.

The chariot near Pompeii was discovered in a wealthy suburban villa, used in life for community festivals and processions. Decorated with bronze and tin medallions depicting Cupid, the Roman god of love, and other erotic scenes, Massimo Osanna, the outgoing director of the Pompeii archaeological site, has speculated that, up until the point it was buried in volcanic ash, it may have been used in wedding rituals, “for leading the bride to her new household”.

© Archaeological Park of Pompeii - http://pompeiisites.org/en/comunicati/the-four-wheeled-processional-chariot-the-last-discovery-of-pompeii/

© Stefano Bolognini

The carriages in Thrace, on the other hand, were deliberately interred in a large tumulus after having been used to convey the dead to the site for burial. There, the horses would have been ritually killed and buried alongside their owners; a conspicuous display of the wealth and status of the deceased.

The burials also included large numbers of grave goods to accompany the dead in the afterlife, including clay, glass and bronze vessels, bronze lanterns, weapons, jewellery, and wooden boxes.

In both cases, however, their respective archaeological contexts resulted in their remarkable preservation. Their discovery nearly two millennia later has brought into sharper focus the construction and design of ceremonial chariots and carriages in the ancient Greco-Roman world.

© Spiritia

© Ministry of Culture and Sports

The planned enhancement of the Mikri Doxipara-Zoni site

Since the impressive discovery of burials, carriages and horses at Mikri Doxipara-Zoni in 2002, the Ministry of Culture decided to create an exhibition center in the area of the tumulus.

Plans for the center will include reconstructions of the carriages and human burials, providing a full graphic display of the site as it was uncovered by the archaeologists. The center will also present the daily life of the ancient inhabitants of the area, as well as their rituals and customs associated with death.

In a recent statement, Curator of Antiquities in Evros, Domna Terzopoulou, told the Athens-Macedonian News Agency that work to showcase the burial mound will begin immediately.