One beautiful December morning 15 winters ago, I visited the island of Kastellorizo for the first time, knowing little of its special history. Looking at the picturesque fishing village that made up the island’s only settlement, it seemed to me that time had simply stopped here several decades earlier, leaving a vista of abandonment and ruin. However, I only realized the true magnitude of the disasters that have befallen this island when, in a local convenience store, I spied a panoramic photograph of the port, taken in the early 20th century.

The image showed the same harbor and the same hill as I had seen moments earlier, but instead of what I’d seen outside, in the picture there stood hundreds of houses, one right next to the other, without a single gap in between.

At first, I wondered whether this was a real photograph or the work of someone’s imagination, as I couldn’t believe that the settlement that I was now standing in had once been such a densely populated harbor town. After all, the promontory of Kavos that I’d glanced at a few minutes earlier was covered in ruins and wild fig trees.

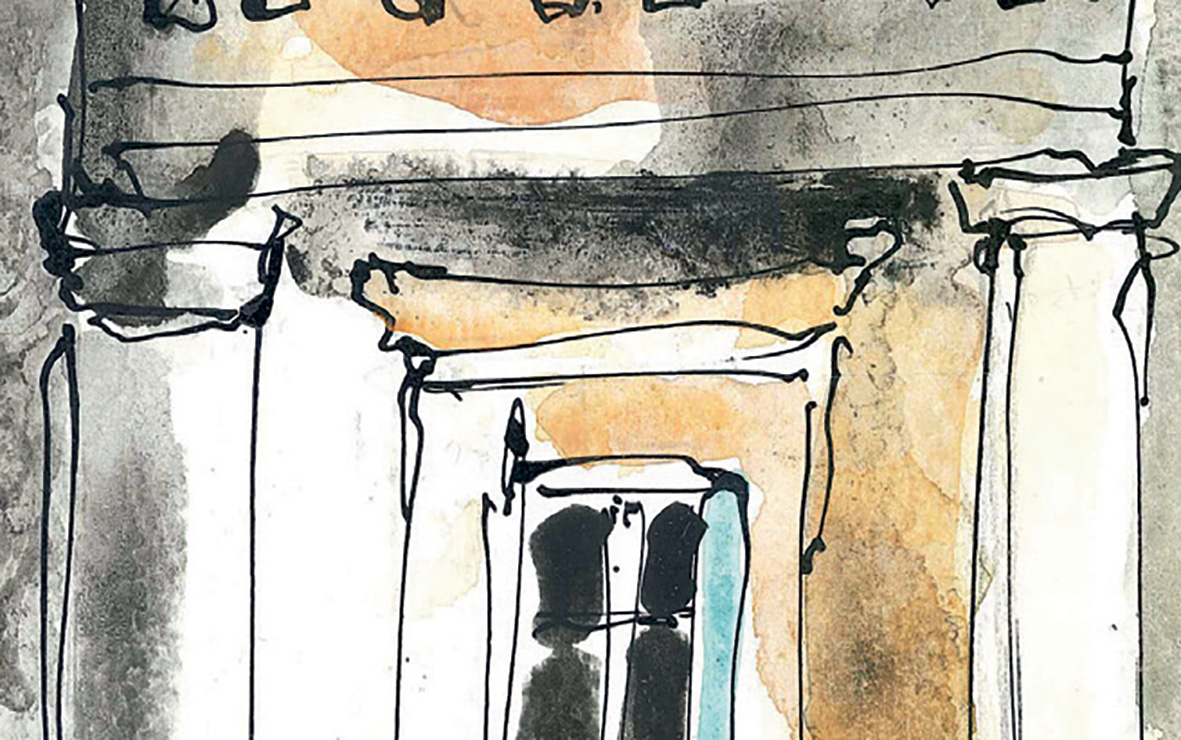

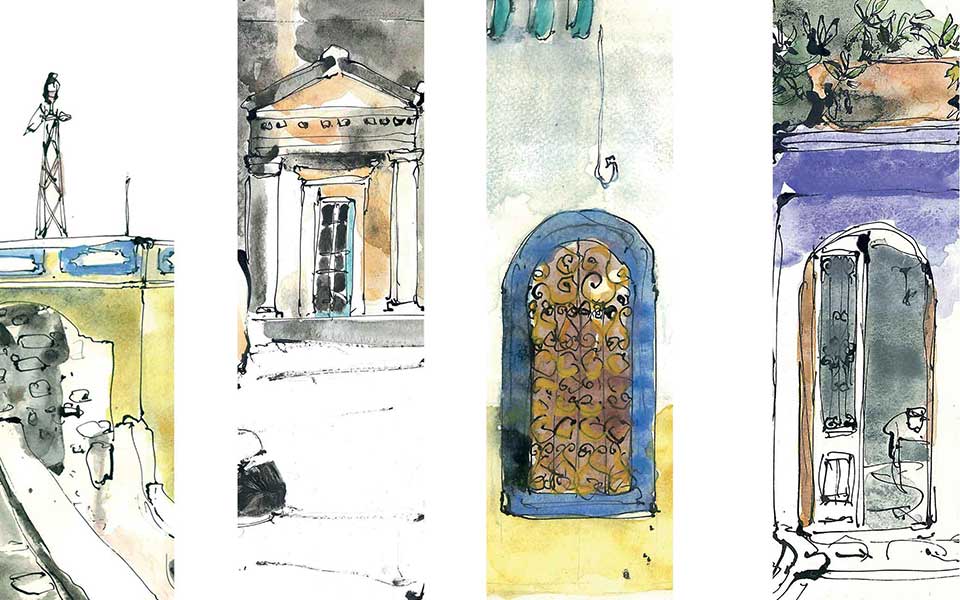

© Watercolor by Pavlos Habidis courtesy of the Hellenic History Foundation (IDISME)

The contrasting images swirled in my mind for days and months after I returned home. Archival material, including photographs and planning designs, were said either to be lost or scattered to the ends of the earth where the island’s expatriates had migrated, taking with them all their stories and all the secrets of the place.

Nonetheless, unanswered questions about a community and a once-flourishing culture that had left a unique architectural imprint nurtured in me a desire to return and explore the settlement in depth. And so, a few years later, I began the wonderful work of systematically recording the architectural legacy of what was left of the town as part of my doctoral dissertation, “The Residential Development of Kastellorizo in the Post-Revolutionary Years until the Integration with the Greek State,” for the School of Architecture at the National Technical University of Athens.

On a little rock at the edge of the Aegean Sea, a relatively small Greek population earned its living from the sea for centuries. The island’s advantageous position, combined with favorable conditions for the development of maritime trade, made Kastellorizo an important seaport from well before the 18th century.

After the Greek Revolution, Kastellorizo experienced a surge in population and a frenzy of residential development. Over a period of 40 years, the population more than tripled, as migrants from other islands rushed to share in this minor economic miracle. With available land around the port no longer sufficing, a part of the settlement was even built on land reclaimed from the sea.

© Watercolor by Pavlos Habidis courtesy of the Hellenic History Foundation (IDISME)

Space for construction was in high demand, and the existing dwellings, with the characteristic cubist form that prevails in the Aegean area, were gradually replaced by two and three-storey houses with pitched roofs.

Ships brought not only products but ideas, and Kastellorizians came to enjoy a cultural enrichment that was reflected in the architectural landscape.

Cosmopolitanism, through contact with the coast of Asia Minor and with other peoples of the Mediterranean, created a unique cultural blend of East and West, influencing a style of domestic construction that combined oriental and neoclassical elements. (A century later, expatriate Kastellorizians motivated by the desire to give back to their ancestral community, would play an active role in the construction of public buildings that also embraced this style of architecture.)

The story of the town of Kastellorizo is to be found in its historical layers. Since antiquity, human settlement on the island was centered on the promontory of Kavos, a location with strategic advantages. A fortified tower standing between two natural harbors controlled trade routes to the eastern Mediterranean.

In medieval times, this fortified core evolved and expanded, forming the first residential precinct. During the years of Ottoman domination, the town gradually spread “amphitheatrically,” following the contours of the natural landscape.

© Watercolor by Pavlos Habidis courtesy of the Hellenic History Foundation (IDISME)

The urban fabric was extremely dense, with serpentine lanes. Churches and schools were erected in the little public space that was left. The rigid social and ethnic stratification was reflected in the existence of exclusive neighborhoods. The privileged area of Kavos was dominated by wealthy shipowners. The areas of Mesi tou Yialou (“Mid-Coast”) and Kavoulaki (“Little Cove”) were home to merchants. In Pigadia (“Wells”), one found seamen and the working classes, while the small Muslim community, mainly civil servants and their families, remained safely huddled around the Kastro (“Castle”).

As the population began to decrease in the last two decades of the 19th century, construction fell into decline, while significant destruction of the town began with the shelling that took place in WWI and with the catastrophic earthquake of 1926.

During the Italian occupation (1921-1943), targeted urban interventions were implemented which sought to consolidate the authority of the regime through the construction of public buildings with colonial and eclectic characteristics. The architectural landscape changed dramatically with the savage destruction of much of the settlement during the bombardments of 1943 and the devastating fire of 1944.

Since its integration into the Greek state in 1948, the settlement has struggled to heal its wounds. Only a relatively small part of the original town has been preserved intact, while large sections still remain in ruins and overgrown.

Since the 1990s, the restoration of dilapidated family homes by Greek-Australian expatriates has helped to restore the built environment, while other Europeans – mostly Italians and French – have been attracted by the charms of what remains of the town and by an image that combines myth and nostalgia for the golden age of the island.

Happily, during the last decade, there has been an increasing trend towards faithful restoration, not only of ruined houses, but also of public monuments, assisted by the generosity of expatriates and distinguished friends of Kastellorizo. In general, the restorations have been governed by respect for the traditional character of the settlement, but there are also unfortunate examples that have forever altered the authenticity of the built environment.

Clearly, it is essential that we all contribute to preserving those special characteristic features of the town which are an integral part of the island’s architectural heritage. Let us hope that all of us who participate in this gradual process of restoration appreciate that we are only temporary guardians of Kastellorizo’s architectural legacy, a legacy which must be preserved and passed on, intact, to future generations.