A visit to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens is always lots of things: educational, yes, and certainly interesting, but more importantly, it’s a tonic for when you’re in a funk.

Wandering among the figures of Pan seducing Aphrodite, the korai, the sphinxes and the pouting Roman busts is guaranteed to lift even the darkest of moods.

For some, one reason is the museum’s location on downtown Patission Street, near the cool neighborhood of Exarchia where, in the 1990s, every self-respecting Athenian teenager had their first night-on-the-town experience. Today, for these same individuals who are now all grown up, a visit to the National Archaeological Museum is also a trip down memory lane – and perhaps that alone is worth the visit.

© Eleftheria Alavanou

For this, and so much more, I love the NAM. I visit it more often than any other museum in Athens and take photographs of pieces that catch my attention (no flash, of course!) so I can look them over later.

Browsing through my NAM album recently, I was struck by the many different ways that the female figure was depicted in ancient Greece: goddess, hunter, leader, curly-haired maiden, commanding sphinx, inconsolable siren, introverted poet.

We know that ancient Greeks did not hold women in the regard they deserved, and that, even in the illustrious Athenian Republic, women were lumped together with other second-class citizens without rights, such as slaves and foreigners.

Yet even an untutored eye can see from the depiction of female figures in ancient statuary and pottery that the perception of women was more complex than that. Women weren’t simply ornamental creatures or flawless paradigms of virtue (to mention two of the more common stereotypes found in Western culture 2,500 years later), although elements of both such attitudes towards them can be found in ancient works.

© Eleftheria Alavanou

© Eleftheria Alavanou

Hunter, ruler, lamenter

How then were women portrayed? Sometimes as skilled hunters, as evidenced by the marble statue of Artemis, a Roman replica of a 4th-century BC Greek work. Even though we can’t see the statue’s facial expression or fully understand the movement the sculptor was suggesting – the figure has no head or arms – it nonetheless emits tremendous energy through the billowing skirts and alert pose. The figure also exudes strength, a trait usually reserved for men but allowed by the ancients in their female divinities.

The statue of Cybele (400-350 BC) is of a different style, though it also depicts authority. With a small lion on her right and a scepter (unfortunately broken off) in one hand, there is no doubt that this mother goddess is all-powerful. Sitting on a throne, she resembles a female form of Zeus, a revered figure no one would dare challenge.

The statue of the Siren (330 BC), a mythical woman with the wings, legs and tail of a bird, runs along more stereotypical lines. It was found at the Ancient Cemetery of Kerameikos in Athens where it had served to lament the passing of the man buried within the tomb it graced. The siren’s expression is etched with pain and grief, sentiments traditionally ascribed to women rather than to men, who were meant to have greater hold over their emotions.

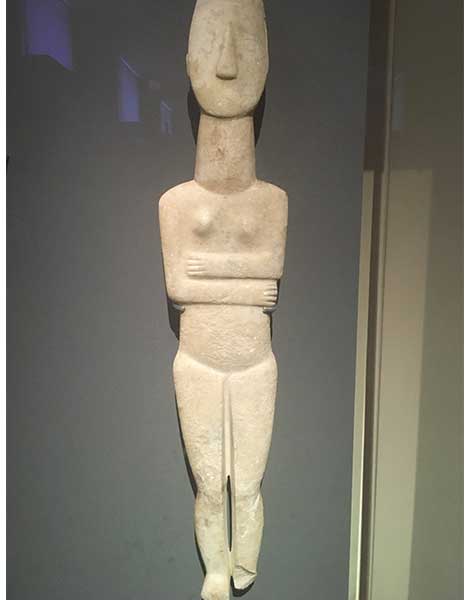

On the other end of the spectrum, the early Cycladic marble figurine (2800-2300 BC), is anything but a stereotypical depiction of a female. Standing 89 centimeters tall and possibly sculpted in Naxos, it is one of the tallest of its kind and features a square form that could have passed for a representation of a male were it nor for its breasts.

© Eleftheria Alavanou

© Eleftheria Alavanou

Poet, beauty, empress

With her thin chiton and himation, the female figure sculpted from thin slabs of limestone (known as ‘titanolithos’ or titans’ stone) who appears on a funerary stele is simply delightful. What may be overlooked at first glance but lends this composition such magic is the pile of scrolls beneath her stool, pointing to her being a woman of letters, possibly a poet.

Equally enchanting is the marble head of a young woman with an exceptionally ornate hairstyle. A study of her rather odd features and a comparison with other similar sculptures indicates that this is no ordinary Classical-period woman – indeed, the sculpture is believed to date to the reign of Roman Emperor Trajan (AD 98-117).

© Paul Munhoven (CC BY-SA 3.0)

I have saved my favorite female figure in the entire museum for last: that of Julia Αquilia Severa, the wife of another Roman emperor, Elagabalus. This portrait statue is made of separate pieces of bronze and its subject’s face is deeply indented.

This disfigurement was not the result of damnatio memoriae, or “condemnation of memory,” a punishment worse than death that had been meted out to other members of the Severan dynasty. The statue was, in fact, damaged in a fire, an unfortunate incident that nonetheless has stood the artwork’s subject well over time, as Julia’s is a portrait one is not likely to forget.