Since the Covid-19 coronavirus began its lethal spread across the globe, newspapers, television and the internet have increasingly referred to the terrible plague of ancient Athens: an epidemic that broke out in 430 BC, in the second year of the Peloponnesian War. The losses were great and the symptoms, as described by Thucydides, were dreadful and included headache and severe fever, hoarseness, cough, nausea, diarrhea and rashes.

The deadly plague filled many graves in Athens at the time; Pericles was reputedly among its victims. The plague, says archaeologist Dr Melpo Pologiorgi, “may have been typhoid fever, according to the latest academic studies, which returned to the city twice more, in 429 BC and the winter of 427/426 BC, resulting in an even greater rise in the number of victims.”

Now, in the 21st century, similarly plagued by a pandemic, we can look back with greater understanding on the world of health in ancient Greece, including the role of the god of medicine, Asclepius; the healing centers of the time, called Asclepieia; and health-related votive offerings.

Our primary focus is an unpublished votive relief depicting Asclepius – brought to light in 1994 by Pologiorgi during the archaeological excavation of the Makryiannis plot, prior to the construction of the new Acropolis metro station. The relief-carved stele, still intact and well preserved, was originally set up in the sanctuary of Asclepius on the south slope of the Acropolis. Today it is part of the collections of the Acropolis Museum, so far unseen by the public, although it will soon be reported on in a scholarly archaeological journal.

The late Classical relief (340-330 BC), on a stone slab measuring 49 cm high x 74 cm wide, is framed by two columns supporting a tiled roof visible above. The scene is impressive: on the left, divine Asclepius sits surrounded by his offspring, while, on the right, a mortal family of worshipers approaches the god to offer him a sacrifice, possibly as a token of their gratitude following some treatment. Wearing a himation, Asclepius is comfortably seated on a thick cushion, his arms lying along the arms of his throne, his feet resting on a footstool.

“The god,” Pologiorgi explains, “raises his left hand with a majestic movement and probably once wielded a scepter, originally rendered in paint, as indicated by his grasping fingers. Beneath the throne lies a coiled serpent, a characteristic symbol of Asclepius, which was often involved in the treatment of patients, as we see in some reliefs.” Behind the throne, a standing adult female is identified as Asclepius’ daughter Hygieia, while another female beside her, half-hidden by Asclepius, likely represents a younger daughter.

In front of the god, the two naked young men without beards are his sons, who also had healing abilities. The youth whose chlamys (short robe) is draped over his raised left arm recalls a typical heroic figure; “as the most prominent of the two, he can be identified with Machaon, known from literary sources for his surgical skills.” Behind him stands Podalirius, Asclepius’ youngest son. “Signifying the close bond between the two brothers, Podalirius grips Machaon’s arm with his right hand. This gesture is rather uncommon, although we have found it in two other votive reliefs dedicated to Asclepius.”

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Particularly poignant is the family of pious worshipers on the relief’s right side. “It is preceded by a young slave, who leads a pig to be sacrificed on the altar. The pig, just one kind of animal that might be offered to Asclepius, is seen on several sculpted reliefs from the Asclepieion on the south slope.

“Sacrificing a pig may have become an acceptable practice at the Asclepieion thanks to the close relationship between the healing god and the Eleusinian deities Demeter and Kore. Pigs were a common dedication to Demeter, and Asclepius had been ‘hosted’ at the Eleusinion in Athens (beside the Panathenaic Way on the north side of the Acropolis) until his own sanctuary was founded (ca. 420 BC).”

The family of worshipers is led by an old man with a long beard, wearing a himation, who probably represents the grandfather. His raised right hand signifies reverence and respect for Asclepius. Following him are two parents and four children.

The relief is well preserved because the slab had only its back side exposed. After the abandonment of the Asclepieion, the carved votive slab was reused as building material to line and stabilize the inner western face of a main sewer line, dug through soft rock (“kimilia”), which, from at least Hellenistic times, had operated beneath an ancient road.

“This ancient road descended the southern slope of the Acropolis in a NW-SE direction, beginning from the sacred enclosure (temenos) of the sanctuary of Dionysus Eleftherios with its large theater. It was in use from at least the early 5th century BC until the middle of the 7th century AD.” Part of it had previously been excavated in the basement of the Weiler Building, just in front of the Acropolis Museum; another section was investigated north of the same building during an excavation by the University of Athens; while the third and longest stretch was revealed on the Makryianni plot, under Pologiorgi’s watchful eye, when construction works began for the Acropolis metro station.

Pologiorgi vividly recalls the day the sculpted relief was discovered: “I managed to enter the ancient sewer where the slab stood, and passing my left hand into a crevice up to the level of my wrist I was able to probe its hidden front side – only to realize I was touching what felt like a lot of legs!” Later, on a pleasant October afternoon, after the slab had been removed, it was confirmed to be a remarkable work of sculpture, preserved for thousands of years in excellent condition.

© De Agostini/Getty Images/Ideal Image

The divine physician who brought hope

According to myth, Asclepius was a mortal, although the son of Apollo, and was raised to become a healer. In the 5th century BC, he was deified and assumed the dual role of god and doctor. His cult came to Athens from Epidaurus, first arriving at Piraeus.

“In 420-419 BC, a few years after a deadly epidemic first struck the city of Athens and devastated its population, Telemachus, a pious citizen from Acharnes, founded the sanctuary for Asclepius and his daughter Hygieia on the southern slope of the Acropolis,” says Pologiorgi. “Although the cult of Asclepius has been documented in other places in Athens, even in an ancient private house with a garden between Thiseio and Kerameikos, the Asclepieion on the south slope became the city’s most important ‘medical center.’

“Moreover, its popularity – stemming from its crucial role in the health and salvation of the public, without regard to social status – led to this Asclepieion being very long-lived. It continued to operate until at least the middle of the 5th century AD, while the worship of other pagan gods had already declined significantly.”

After the destruction of the Athenian Asclepieion (late 5th or early 6th century AD), a three-aisled basilica – probably dedicated to the early Christian healing saints Cosmas and Damian, Orthodoxy’s “unmercenary healers” (Anargyroi) – was erected over its ruins.

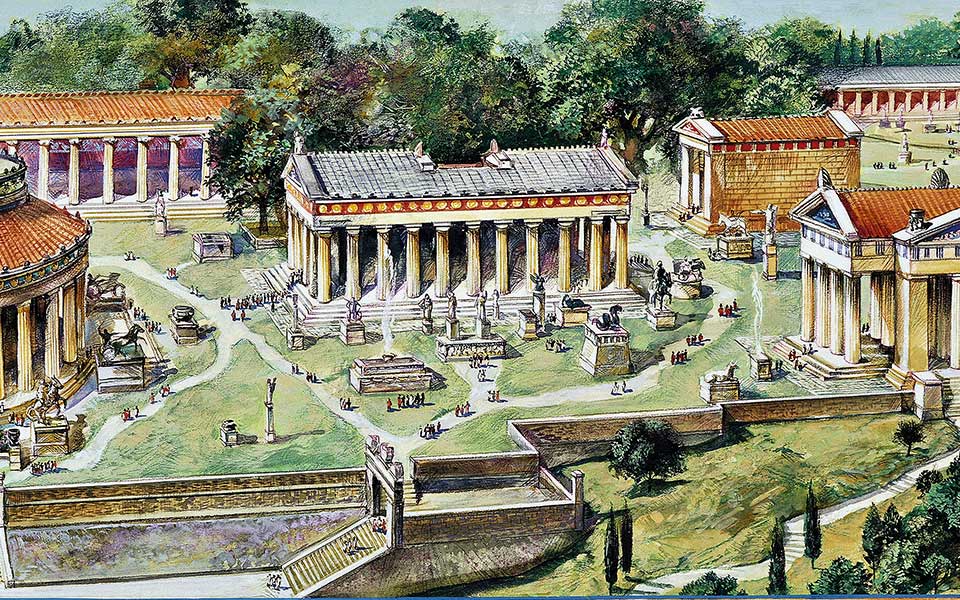

The sanctuary of Asclepius in the shadow of the Acropolis was founded in an ideal location, beside a natural source of clean water (the “Sacred Spring”), which represented an essential element in his worship. The complex included the god’s temple and altar, as well as two stoas.

In the larger, Doric stoa (Abaton), patients experienced “dream healing” (enkoimesis). They were given therapeutic herbs in order to sleep and dream of the god, who would come to them and either heal them outright or prescribe a cure. In the morning, patients related their dreams to the Asclepieion’s priests, who determined a treatment accordingly. In some cases, patients even underwent surgery.

This important sanctuary, Pologiorgi tells us, did not possess the widespread reputation of the Asclepieion at Epidaurus, “but it was of great importance to the Athenian masses.”