Ιn the few surviving lines of his lost tragedy “Rhizotomoi” (Root Cutters), the playwright Sophocles (496-406 BC) describes the notorious sorceress and healer Medea, naked, chanting and averting her eyes as she collects in a bronze vessel the silvery secretion oozing from the root of a plant sliced open with a bronze sickle. As other surviving literary sources also make clear, this disturbing theatrical scene depicts practices not unlike the methods of actual root cutters of that era.

We know that the years during and just prior to the Peloponnesian War were a time of terrible adversity, and we know, too, that in times of crisis, people sought solace more in magic than rationality – two disparate approaches to healing that coexisted and were in perpetual conflict throughout the long history of the Greek therapeutic arts.

Who were the root cutters? They were experienced collectors of usually wild herbs and roots, who sold their products directly to physicians, or who served as suppliers to medicine sellers. This quite profitable enterprise was, as we would now say, a “closed profession,” as the collectors jealously guarded their empirical knowledge about where, how and when to gather therapeutic plants from those who did not belong to their “guild.”

One of the earliest Greek root cutters was the semi-mythical philosopher, seer and poet Epimenides of Crete (7th/6th century BC), said to have successfully cleansed an Athens guilty of sacrilege after the Cylonian Affair (632 BC), when a failed coup led to a massacre outside a temple. The poet is also known for his herbal blend called “alimon,” a small draught of which he drank every day in order to never feel hungry.

A number of other interesting figures belonged to the magical-mythical circle of root cutters, as well, including the centaur Chiron, Achilles’ tutor; the healing god Asclepius; the witch Circe; the soothsayer-healer Melampous; and Machaon and Podaleirios, the physician-sons of Asclepius, who served in the Trojan War.

Among the most distinguished historical practitioners of this age-old tradition was the physician Diocles of Karystos (375-295 BC), who reported on medicinal plants, their uses and how to collect them in the now-lost treatise “The Art of Root-Cutting.” Fortunately, lengthy extracts from this work are thought to be preserved in the contemporary writings of Theophrastus (371-287 BC); they’re definitely in Dioscorides’ early pharmacopeia (“De Materia Medica,” 1st century AD), where he describes in detail the healing powers of many roots.

Another well-known root-cutter was Crateuas (1st century BC), personal physician to Mithridates VI, King of Pontus and a great opponent of Rome. Following a request from Mithridates, who understood his enemies sought to poison him, Crateuas, using dozens of herbal ingredients, concocted the famous Mithridatium. This honey-based mixture, taken in small daily doses dissolved in wine, was believed to be an antidote for all poisons. Crateuas also authored his own “Art of Root Cutting,” which had a powerful, far-reaching influence. In this pioneering work, the author not only described the properties of the medicinal plants he used, but also included color illustrations, thus providing an invaluable reference guide to ensuing practitioners.

The importance of roots in ancient Greek medicine related not only to their active ingredients but to their symbolic significance as well. Produced within the embrace of the all-nurturing, all-providing Earth Goddess, they also constituted (in the hands of the chthonic goddess Hecate) effective weapons for the healing of body and soul. Moreover, the sacred serpent, thanks to his underground explorations, knew all the secrets of the roots and had the power to use them for the benefit of the many patients who frequented Asclepius’ healing sanctuaries (asclepieia) seeking to be cleansed and cured.

Among the numerous roots used by ancient Greek physicians, seven of the most prized are presented below. With all the stresses of modern living, and with all the health problems often associated with them, some of these curatives may again prove useful. It might, therefore, be to our advantage to welcome, once more, nature’s roots as Mother Earth’s generous gifts to humankind.

© George Sfikas

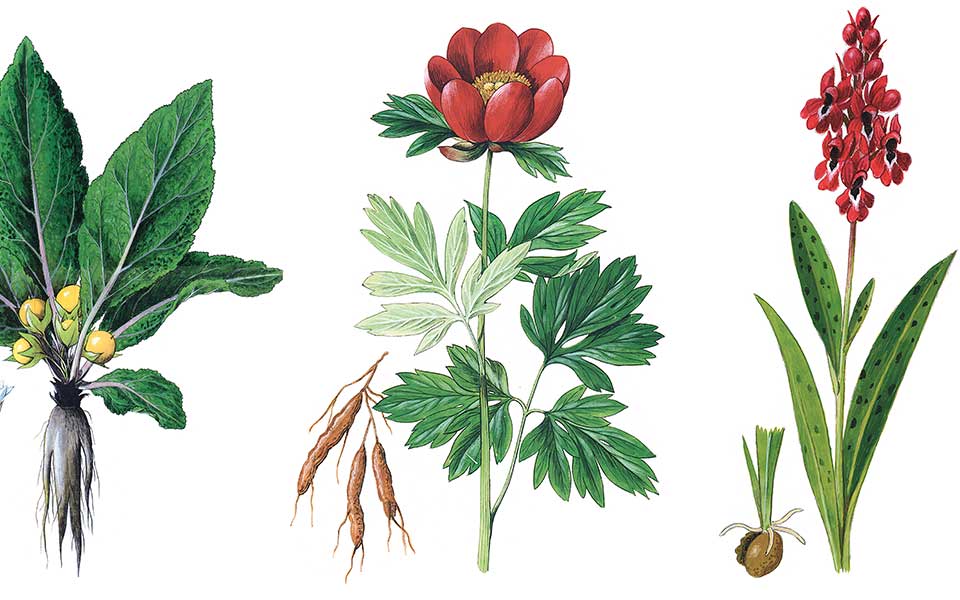

Marsh Mallow

The marsh mallow (Althaea officinalis) is cultivated in many countries, since even those uninterested in its healing powers are readily impressed by the abundant flowers it presents every spring. The plant’s greatest asset, however, is its notable medicinal properties, something accurately emphasized by that ancient authority, Dioscorides, in “De Materia Medica,” who reports: “it is called althaea due to its many curative powers and its multiplicity of uses” – the name having been derived from the ancient Greek verb althaino, meaning “to heal.”

Ancient Greek physicians used to add the root to grape must and, after a period of fermentation, administered the resulting wine for the healing of wounds and abscesses. They also believed that, when it was prepared as a decoction, it was beneficial against medical conditions ranging from dysuria and kidney stones to dysentery and sciatica.

Today, its sweet, mucilaginous root is used to relieve non-productive coughs and offers great service in cases of gastritis and enteritis, while poultices made from it aid in recovery from burns and wounds; the efficacy of these uses are supported by our present understanding of the plant.

© George Sfikas

MANDRAKE

The root of the mandrake (Mandragora autumnalis), a plant which thrives in rocky places in the Cyclades and Crete, often exceeds half a meter in length and branches out at the end. Thanks to its appearance (often resembling a human figure) and its hallucinogenic effects, popular imagination has linked the mandrake to magic and associated it with a multitude of myths.

The earliest mention of its pharmacological effects is found in the Odyssey, according to many Homeric scholars; mandrake root is identified as the main ingredient of the magic potion Circe uses to transform Odysseus’ companions into pigs, by covertly adding it to the dishes of food she offered them.

Theophrastus, in his “Enquiry into Plants” describes what precautions the root cutters of his era took to protect themselves from its catastrophic power: they would draw three circles around the plant in the dirt with a sword, then dance around it cursing before finally digging out the valuable root while looking westward.

In ancient Greece, one who wore a mandrake-root amulet believed it would ensure him sexual prowess and success, and protect him from wild animal attacks, sudden illnesses and bad luck.

The root was used by practitioners of the healing arts, too, for its analgesic and narcotic properties. With the “mandrake wine” they brewed – the root’s bark having been left to ferment for three months in grape must – doctors treated snake bites, alleviated pain and combated chronic insomnia. With larger dosages, they could induce a deep lethargy, greatly welcomed by those about to undergo surgical procedures. However, great care was required in its dispensing; otherwise, when the patient awoke, he would likely find himself in the Underworld.

© George Sfikas

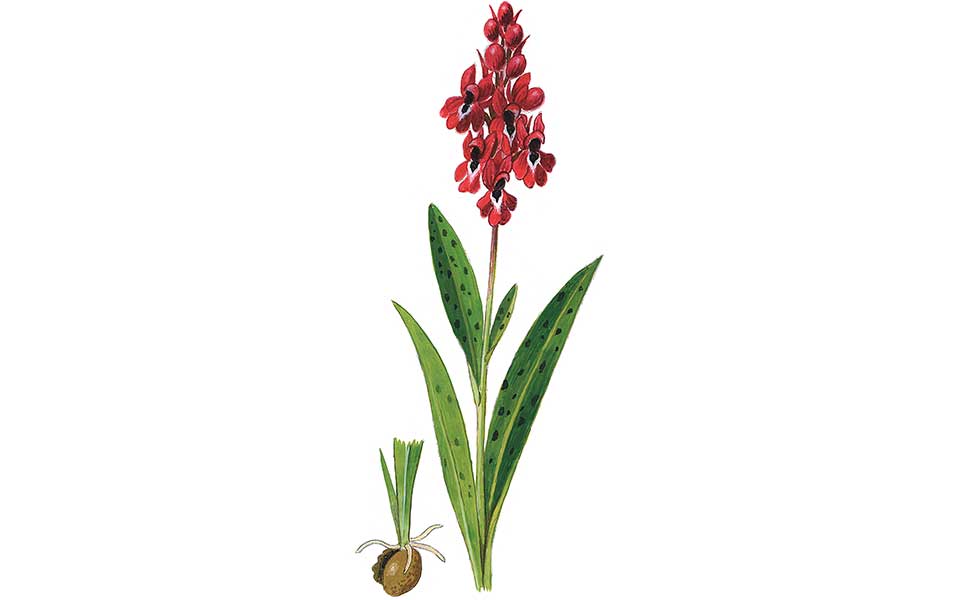

Early purple ORCHID

The production of a traditional beverage called salep, for easing coughs and soothing stomach aches, is an art of the East, which became known in Greek lands under the Ottomans. It is prepared from the tubers of a beautiful orchid, the early purple orchid (Orchis mascula), which few today realize was held in high esteem in ancient Greece.

It was then called orchis, after the name of a certain young man, the son of a nymph and a satyr. One fateful night, during an orgiastic ritual in honor of Dionysus, the reckless youth misbehaved and stole the virtue of one of the god’s maidens. Immediately, the maenads, the god’s female followers, tore him to shreds. In the throes of sorrow, his father beseeched Dionysus to forgive him and to restore him to life. And the god did, at least to a certain degree, as from the remains of the testes of the inconsiderate youth there sprang an orchid.

In ancient times, amazing qualities were associated with the underground part of this plant, most likely because of its resemblance to the male genitalia. An age-old belief about sernikovotano, as the orchid is now popularly known in Greek, was first expressed by Dioscorides and has been preserved nearly unchanged in many regions: namely, that while the big root, eaten by men, leads to the birth of male children, smaller roots consumed by women will produce girls.

Theophrastus writes about the tuber of an orchid sent as a gift to King Antiochus of Syria. Such was this tuber’s power that one slave managed to satisfy 70 women in a single night, just by holding it in his hand.

Such legendary effects are nothing more, however, than the product of a vivid imagination, as in no part of the orchid have there ever been detected any substances with aphrodisiac properties.

© George Sfikas

LICORICE

The therapeutic use of licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra) can be traced back almost 4,000 years, with an entry inscribed in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (18th century BC) revealing its use as a treatment for asthma.

This is one of the few plants that all traditional Old World therapeutic approaches agree has important medicinal properties. It seems that ancient Greek physicians were taught its use by the root cutters and plant collectors of Cappadocia and Pontus – regions in which it continues to flourish even today. Theophrastus, the philosopher and “Father of Botany,” in his treatise “Enquiry into Plants,” mentions that “Scythian Root” is useful in cases of asthma, non-productive coughs and chest pain.

Some four centuries later, Dioscorides, calling it “Pontic Root” and “Skythion,” recommends it as a curative for harshness of the throat, heartburn, and chest and liver diseases.

The modern scientific view of licorice largely confirms ancient beliefs, attributing its properties to the glycyrrhizin it contains – a substance that also acts as a powerful antiviral. In addition, due to its antispasmodic and anti-inflammatory action, licorice has been discovered to relieve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and Crohn’s disease.

© George Sfikas

ELECAMPANE

Another curative employed by ancient doctors was the root from the plant elecampane (Inula helenium) that Theophrastus describes as “Chiron’s panacea,” including it in the therapeutic arsenal of the centaur Chiron. Four centuries later, we again encounter it in the writings of Dioscorides, where he calls it “elenion.” According to myth, elenion sprang from the tears of Helen as she mourned the loss of her helmsman, during her voyage to Egypt with Menelaus following the fall of Troy.

In ancient medicine, elecampane root found many applications. Physicians boiled it in honey or prepared it as a therapeutic wine to treat spasms, coughing and flatulence, as well as to neutralize the harmful effects of wild animal bites. More generally, it was thought a valuable medicine with benefits for the digestive and respiratory systems.

Most of these age-old uses have been replicated in modern plant therapy, validating the knowledge of ancient Greek physicians. What they certainly did not know, however, as it was only discovered in the early 19th century, is that the root contains a valuable polysaccharide, named inulin after the plant’s genus. The beneficial effect of this soluble fiber on the intestines gives great credence to the ancient belief that elecampane root improves digestion.

© George Sfikas

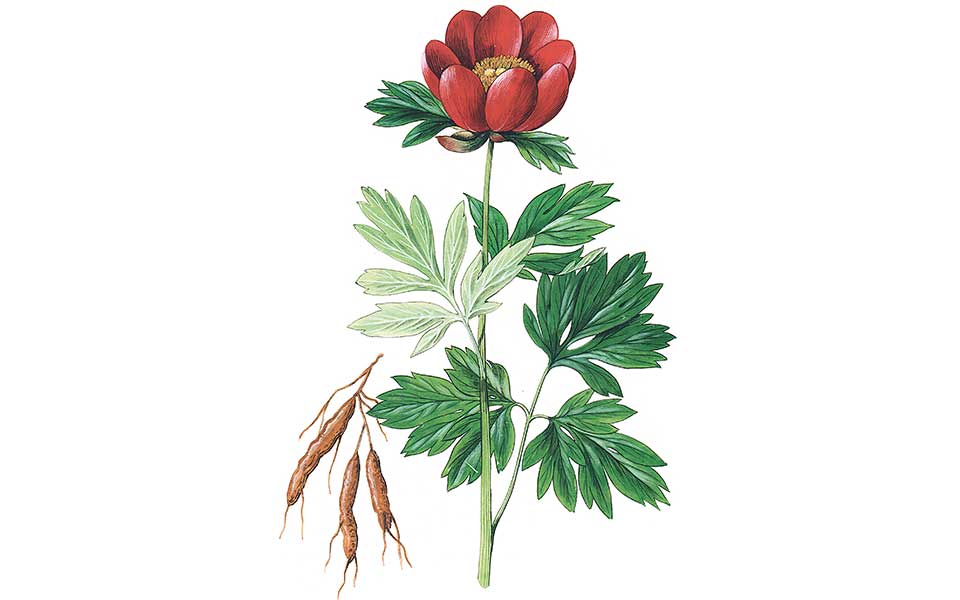

Balkan PEONY

The healer Paean was the physician who treated the gods Ares and Hades, placing therapeutic balms over the wounds they suffered during the Trojan War. As Paean died, according to myth, he was transformed into his namesake plant with large flowers – the peony; this common name refers to the plants that belong to the genus Paeonia, of which five distinct species exist in Greece.

Many ancient physicians considered peonies a panacea – particularly the species Paeonia mascula and P. officinalis, which Dioscorides respectively calls “male” and “female”, and P. peregrina, pictured above. Using their roots and seeds, doctors treated a host of diseases, from women’s ailments and convulsions to persistent nightmares and epilepsy. The demand for every kind of peony was so great in antiquity that false stories concerning their dangers were widely circulated so that professional root cutters wouldn’t have to face serious competition when collecting them.

Theophrastus reports (although he characterizes the story as fanciful) that widespread measures were taken to ensure peonies were only uprooted at night, since, if this operation were undertaken in daylight and a woodpecker happened to see you, you risked having your eyes pecked out or irreparable damage done to your rear end.

© George Sfikas

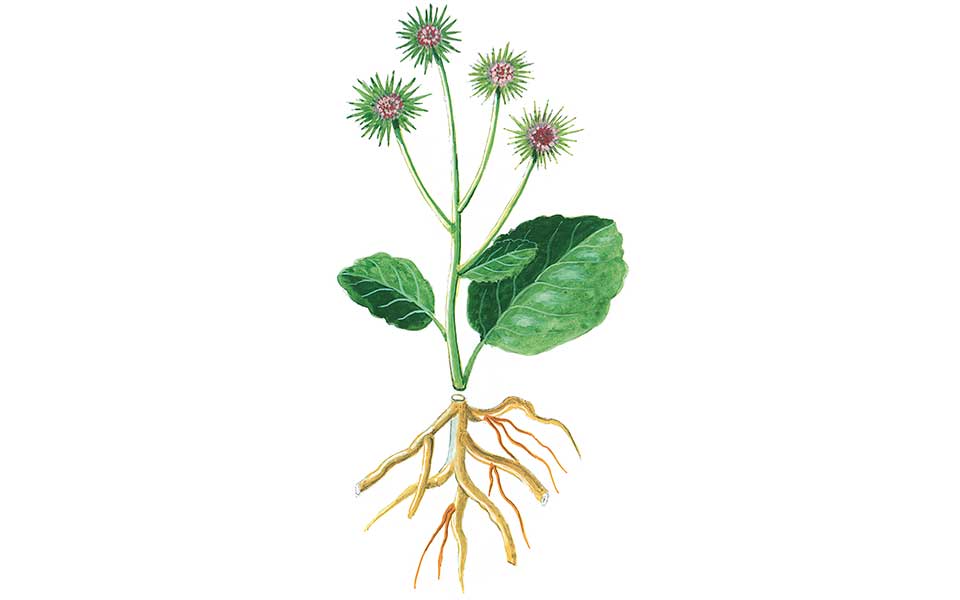

BURDOCK

The root of greater burdock (Arctium lappa), known in ancient times as “arkeion” and “prosopis,” was exploited for many centuries to treat a multitude of medical problems. Ancient Greeks prepared it as a decoction in cases of hemoptysis (coughing up blood) and abscesses, or used it in juice form, blended with honey, to treat burns, snake bites and internal pains.

First and foremost, however, having been prepared by boiling in wine or through a simple, thorough crushing, it was applied locally, to relieve the pain and swelling of sprains and to treat chilblains and infections. Crumbled and mixed with salt, it was spread over deep wounds caused by the bite of a rabid dog. In this way, such wounds were healed more quickly, yet certainly without reducing at all the possibility of the fatal disease being transmitted to the victim of the bite.

Over the centuries, burdock root has largely retained its reputation as a multi-purpose medicine. Some of its present-day applications in plant therapy, such as its prescription for the healing of wounds and ulcers, are proving the legitimacy of its ancient uses. New powers, however, are also being discovered, including its slow but effective result when taken orally in cases of psoriasis and eczema.