Ηaving choices in eating has probably been a human impulse since the dawn of time. One can almost hear the cave dweller saying, “No, I think we should splurge tonight, dear, and have the wild-boar steaks.”

Archaeologists and historians frequently talk about trade in ancient Greece, usually involving raw materials, metals, pottery and the major foodstuffs, but overall diet and the import/export of various fresh or dried commodities other than wine, olive oil and grain are increasingly important, research-worthy topics, since a diverse food supply was clearly also a central, vital factor in ancient daily life.

In the world of the ancient Greeks, just as in our world, food’s life-giving power came to be intertwined with religious belief, and the occasion of its availability or plentifulness called for gratitude to be ritually expressed to the responsible god or goddess.

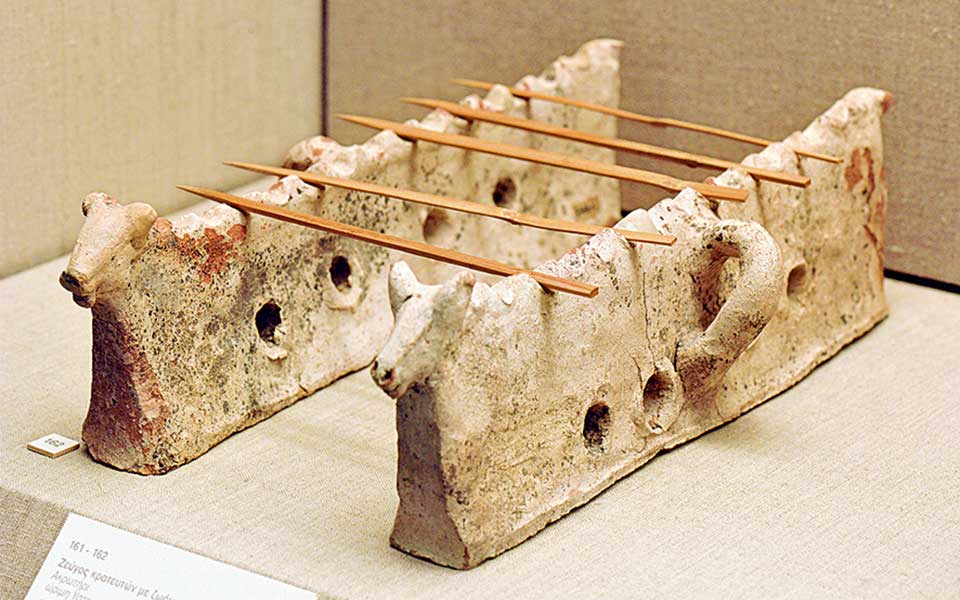

Homer’s poems reveal that close ties already existed between food, religion and mannerly, ritualistic social conduct as early as the Late Bronze Age and the early centuries of the Iron Age. So valued and universal were the bronze or iron spits used at feasts for roasting meat over the fire that, by at least the 8th c. BC, they had become a form of currency and were often bestowed as dedicatory offerings in religious sanctuaries such as Olympia and Delphi.

In the 5th and 4th centuries BC, wine was the celebrated social lubricant at symposia (evening parties) in Athens and other Greek city-states, while food and its preparation were transformed into a complex, sophisticated art form practiced by elite chefs and described in noted “cookbooks.” Food themes and imagery were also a ubiquitous feature in popular entertainment, especially in the political and social satires of the comedic playwright Aristophanes.

Greek cuisine went on to influence Roman and Byzantine tastes, with the elaborate rituals and the exuberance associated with ancient communal dining ultimately becoming recognized as an iconic aspect of classical culture.

Today’s studies of ancient food greatly benefit from the extraordinary variety of evidence and innovative analytical approaches that researchers now have at their fingertips. Through texts, vase paintings, wall frescoes, botanical and bone remains, archaeological artifacts and architectural knowledge related to pantries, kitchens and dining rooms, along with scientific detection of food residues preserved in dishes and storage vessels, we can now, more than ever, appreciate the diverse diet and the eating habits of ancient Greeks, and marvel at the eternal roots of our own “Mediterranean Diet.”

© Bridgeman Images

A Loaf of Bread, a Jug of Wine…

The Greek land and seas, as all who have spent time in Greece can attest, offer a remarkable variety of edible items that make eating here – even on simple occasions – a pleasurable, palate-intriguing experience. Distinctions existed, however, in ancient times (just as they do today) between basic fare, such as what one might eat at home during an ordinary meal, and the broader range of delicacies served at private or public banquets.

Food, then as now, was an identifying mark of culture – both of Greek versus foreign (“barbarian”) culture, and of the sub-cultures within Greek society, defined by economic or social rank.

Bread, wine and olive oil were universal staples of the ancient diet. Whole-wheat bread (there was no bleached, refined white flour), today still considered a primary “staff of life,” provided energy, vitamins, protein, regular bowels and feelings of fullness and satisfaction. Bread-baking had already been developed in Neolithic times, as evidenced by courtyard ovens discovered at Sesklo (7th/6th millennium BC). Wine and olive oil, as well as whole olives, supplied essential calories and were consumed at all times of the day. A typical breakfast or snack in classical Greece customarily included bread dipped in wine.

Attitudes toward Meat

Homer’s epic heroes ate plenty of roasted meat, usually lamb, goat or pig, but meat consumption was not as common in antiquity as it is today, instead often being reserved for celebratory feasts or featuring only occasionally in one’s weekly or monthly program. Animals, including cows, birds (thrushes, doves, quails, blackbirds, geese), wild hare and deer, were likely more regular food items in the countryside than in the city.

Various types of seafood (especially fresh or dried/salted fish), river/lake fish and eels were also frequent menu items. Less-advantaged members of society, as well as the priesthood, had access to meat through religious sacrifices that ultimately amounted to a key mechanism of social redistribution.

Strict vegetarianism, on the other hand, was also a well-known practice, alluded to in the Odyssey and in the Histories of Herodotus, where the lotus-eaters of North Africa were said to have sustained themselves on only the fleshy, seed-bearing lotus fruit of the Ziziphus/Rhamnus bush.

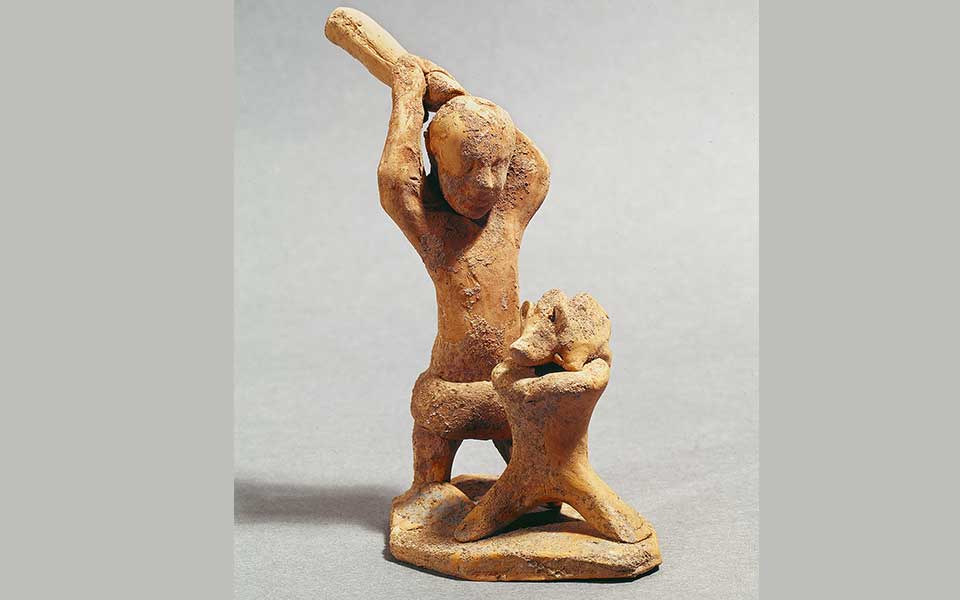

Similarly, vegetarianism was a tenet of Orphism and the philosophy of Pythagoras (6th/5th c. BC), who reportedly likened eating meat to cannibalism and praised the natural abundance of alternative foods: “What else is this but to devour our guests, and barbarously renew Cyclopean feasts? While Earth not only can your needs supply, but, lavish of her store, provides for luxury…” (Ovid, Met. 15.60ff, translated by Brookes More, 1922).

© Bridgeman Images

Never Dine with a Spartan

Simple fare found on an ordinary table might feature lentil soup or a gruel of barley cooked with cabbage leaves and turnips. Kykeon, another widely-enjoyed grain-based product, was described in Homer; it consisted of barley prepared on the fire with wine and goat’s cheese. Humble country or city folk would have supplemented their daily repasts with vegetables, fruit, dried nuts and perhaps some goat’s or sheep’s milk, cheese, or oxygala, a form of yoghurt.

According to Aristophanes, soldiers likewise ate simple meals, sometimes comprising only cheese and onions. The Spartans, noted among ancient writers for their austerity, prepared a black broth of blood and boiled pig’s leg, seasoned with vinegar, which they combined with servings of barley, fruit, raw greens, wine and, at larger dinners, sausages or roasted meat. Spartan boys were sparingly issued barley cakes.

A Fine Spread

The fuller spectrum of foods one might generally find in ancient Greece, in the more liberal, un-Spartan-like households of Athens, or served in the male-only party rooms (androns) used for symposia, included: pulses (lentils, beans, peas, chickpeas and broad beans); vegetables (onions, garlic, wild greens, cabbage, lettuce, turnips, leeks, radishes, cucumbers, celery, dill, fennel, artichokes and asparagus); edible bulbs; mushrooms; fruits (grapes/raisins, olives, figs, apples, pears and plums/prunes); nuts (walnuts and almonds); honey; and various herbs (thyme, marjoram and mint).

Salt was a valued commodity; it was collected on the seashore or mined from salt lakes such as those Pliny the Elder describes at Kition and Salamis in Cyprus. Land snails, particular to Cretan cuisine from as early as the Minoan Bronze Age, were also a desired trade good, which archaeologists have unearthed at Akrotiri on Santorini.

Throughout classical times, as diners became more demanding and their tastes more sophisticated, the spreads that were laid before them expanded correspondingly. In the 3rd c. BC, the “meze” appeared: a meal (popular again today) of many small delicacies that offered guests a delightfully diverse dining experience. The most popular wines came from Thasos, Ismaros (Thrace), Chios, Kos, Lesvos, Mende (Halkidiki), Naxos and Peparethos (Skopelos).

© Bridgeman Images

Compliments (or Not) to the Chef

The names of leading chefs and the details of food, wine and behavior at ancient dinner and drinking parties have come down to us through the writings of Plato, Xenophon, Aristotle, Theophrastus, Pliny, Plutarch, Aspicius, Petronius, Juvenal and a host of other Greek and Roman authors. Their varying opinions reveal that much, sometimes bitter debate and disagreement existed on the merits, shortcomings and appropriateness of contemporary culinary practice and the “party culture.”

The earliest-known Greek cookbooks are a guide to the Sicilian gastronomy of Magna Graecia by Mithaecus (late 5th c. BC) and a gourmet travel book (“Hedypatheia”) by Archestratus of Gela (ca. 350 BC). Mithaecus is skewered by Plato (“Gorgias,” 518b,c) for being an ill-educated chef whose kitchen creations pose a health risk.

Archestratus, also a controversial figure, recorded memorable foods and recipes he had encountered as he toured the Hellenistic Greek world. Sadly, little textual information has been preserved concerning these and at least 20 other classical gastronomic specialists (of some, only their names have survived). Perhaps the most replete source on ancient food and parties comes from Athenaeus of Naukratis (ca. AD 200), who penned a spoof of Plato’s “The Symposium,” filled with names, quotes from past literary works and a wealth of contemporary knowledge on the culinary arts.

Symposia

Since at least Homeric times, feasting in ancient Greece was associated with extending hospitality to one’s friends or foreign guests. By the 5th and 4th centuries BC, many evening parties had become raucous gatherings marked by excessive drinking and eating, philosophical and political debates, dancing, sexual activity and occasionally violent or destructive behavior.

Every well-to-do house had a private dining room for male parties, where the only females allowed entrance were hired flute girls and other female entertainers or courtesans (hetairai).

Men reclined on couches lining the walls, consuming food and drink brought by servants and placed on low tables. They played party games and, as vase paintings illustrate, often engaged in uninhibited communal sex. Some painters show the guests as wine-swilling satyrs: grossly-featured men with horses’ tails and ears who were followers of Dionysus.

Wine was never consumed “straight”; instead it was mixed in large or small vessels (craters) and served from a pitcher (oinochoe) into the guest’s drinking cup (kantharos or kylix). It was the responsibility of the host to allocate the wine and prevent over-inebriation.

The food included finely selected and prepared meats, vegetables and fruit, usually presented in two courses (“tables”). While a humble meal might end with desserts such as boiled chickpeas or fresh or dried beans, or apples or figs, Archestratus advises against these at an upscale symposium, instead offering a delectable Athenian cheesecake, or at least one topped with the superb honey of Attica.

Food as Metaphor in Satire

In the “food-obsessed comic world” (G. Compton-Engle, 1999) of classical Athens, food imagery and metaphors became integral elements in popular satirical entertainment. In plays of Aristophanes produced either during the Peloponnesian War or its troubled aftermath, including “The Acharnians” (425 BC), Peace (421 BC) and “Assemblywomen” (391 BC), plentiful food and feasting symbolize peace as contrasted to the hungry hardship of wartime.

The protagonist of “The Acharnians,” Dicaeopolis, makes a private treaty with Sparta, thereafter enjoying a peaceful life of food, wine, and sex; while in “Peace” the chorus sings of what is essentially a comforting country symposium: “Oh! joy, joy! no more helmet, no more cheese nor onions! No, I have no passion for battles; what I love is to drink with good comrades in the corner by the fire when good dry wood, cut in the height of summer, is crackling; it is to cook chickpeas on the coals and beechnuts among the embers, it is to kiss our pretty Thracian maid while my wife is at the bath.”

Food on the Fly

“Fast food” nowadays often means a quick meat snack such as souvlaki, pita gyros, hotdogs or hamburgers – a class of food widely considered a hallmark of our fast-paced, modern lifestyle. But the ancient Greeks and Romans also ate “on the fly” using only their hands! At prehistoric Akrotiri, racks for grilling meat on skewers and a firebox topped with a flat griddle indicate souvlaki and flat-bread (pita) were already popular nosh some 3,700 years ago.

Homer describes meat roasted on spits (a forerunner of food items such as kontosouvli and/or gyros), and he also mentions the ancestor of the hotdog: “…And as when a man before a great blazing fire turns swiftly this way and that a paunch [i.e. sausage; anc. Greek: gaster] full of fat and blood… eager to have it roasted quickly, so [sleepless] Odysseus tossed from side to side…”

The Romans, too, liked “take-out;” small street-front shops (popinae or thermopolia) in Pompeii featured service windows and countertops with reservoirs for serving wine and warm foods.

The chef Apicius (3rd/4th c. AD) recommended various ground meat dishes, such as Isicia Omentata, a fancy forebear of the burger. Condiments in classical/Hellenistic times included a sauce of milk, animal fat, cheese and honey (an early form of tzatziki), while the Romans had garum, a pickled-fish sauce as common on tables then as ketchup or mustard is today.