Greece has a beautiful relationship with cinema, and Thessaloniki is a particularly film-friendly town. Home to an annual international film festival, coming soon to its 60th year, and a spin-off documentary festival now in its 20th, it also has an excellent museum celebrating the history of Greek cinema from its origins to the present.

The Thessaloniki Cinema Museum, opened in 1997 – the year Thessaloniki was the European Cultural Capital – is now integrated into the Thessaloniki International Film Festival (TIFF). The history of Greek cinema in all of its aspects – technical, aesthetic, historical, and, perhaps most especially, cultural – unfolds like a script.

At this very English-friendly museum, the voice of cinema itself engages us. An intimate, atmospheric first-person monologue in Greek accompanies us throughout the journey. The words appear simultaneously in English on screen, and the narrative is illustrated with clips, subtitled in English. In cinematic semi-darkness, a path connects a series of rooms. At each, we explore different stages of the development of cinema in Greece, starting with a personal description of its birth.

In the very beginning of the 20th century, the Manakis brothers visited Romania. The words of Miltos Manakis himself describe what transpired: “When in the capital of Romania, we realized that in England and in France they sell cameras for shooting ‘live photography.’ This was a piece of news that was really unbelievable and shocking… People in those films reminded us of puppets with their jerky movements and all… This did not stop us from being totally enchanted with film. [My brother] Giannakis would not find peace; he would not go back to Monastir without having obtained a cinematography camera first…”

The brothers began by recording The Weavers in their village in 1905, and continued documenting important events of the time: weddings, festivals, and also political events and conflicts. In the silent and pre-war era, we meet the Fustanella heroes in historical dramas. And then we are surprised by the voyeuristic nudity in the 1931 Clois and Daphne of Orestis Laskos. Slapstick took form through the antics of a Greek “Charlot” (Charlie Chaplin), a Greek Buster Keaton, and a Greek Fatty Arbuckle. These are films rarely seen outside of Greece.

Film in War-torn Greece

During the German occupation of WWII and the civil war that follows, Greek cinema gains a sense of purpose. As elsewhere, films provide comfort to people in two ways: comedy allows them to temporarily forget their troubles, while drama offers catharsis. Neorealism finds its expression in Greece in films like Grigoris Grigoriou’s Bitter Bread, and Black Soil by Stelios Tatasopoulos.

The influence of Hollywood-style scriptwriting, but adapted to the Greek reality, is felt in films like Giorgos Tzavellas’ classic of 1955 The Counterfeit Coin. The same year brings a seminal work defining the urban tragedy; those with even the most superficial introduction to Greek cinema will recognize this pivotal scene: Giorgos Fountas as Miltos, warning Melina Merkouri’s Stella: “Stella, kratao machairi!” (“Stella, I’ve got a knife!”), the air charged with passion, in Michalis Kakogiannis’ Stella – Carmen transposed to Athens.

The Optimism of Finos Films

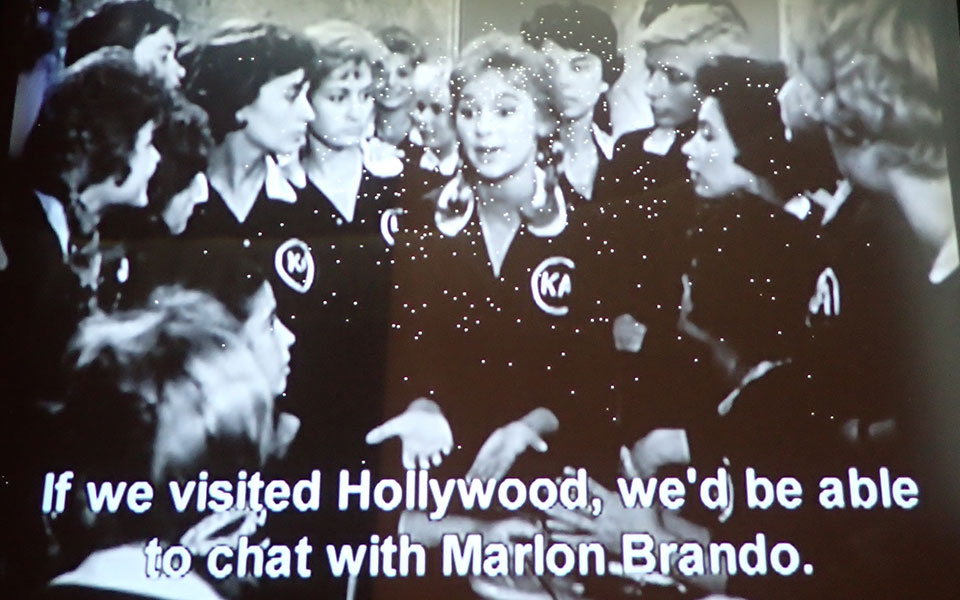

A new room, and an entirely new mood; by the end of the 1950’s and throughout the 1960’s, optimism and humor – and often a lot of color – filled the screen. A well-known clip from the 1959 Maiden’s Cheek illustrates it, where a schoolgirl played by Aliki Vougiouklaki coyly explains to her classmates why it makes sense to learn English (“If we visited Hollywood, we’d be able to chat with Marlon Brando”).

These proto romantic comedies were the primary focus of the Finos Films production company, who essentially perfected the genre. The films in many instances provide a complete spectrum of entertainment: marked by delightfully complex, tight, mad-cap plots that were often adapted from theatrical scripts, the films would often also include musical performances of the artists of the day, like the bouzouki player Manolis Chiotis and the singer Mairi Linda. Dance sequences, with elaborate costumes and surreal settings, were sometimes incorporated too. Their popular appeal, based on solid artistic value, reaches into the present; many of these films are still enjoyed regularly on Greek television.

The 1960’s brought another development – the Thessaloniki Film Festival, introducing a more cultivated approach to cinema, demanding more of the viewer, but promising greater aesthetic pleasure at the same time. The 1962 film Sky, by the Thessaloniki director Takis Kanellopoulos, represented this new wave.

New Greek Cinema

Continuing on our path through the dim light of the museum, we come to a room that explores the impact of the next decade. The magazine of the era Synchronos Cinematographos (Contemporary Cinema) marks 1971 as the year that introduced the “New Greek Cinema,” mirroring France’s Nouvelle Vague, the Free Cinema of Great Britain, and Italy’s era of the great directors.

The New Greek Cinema, in contrast to the collaborative approach taken by Finos Films, was the product of the singular vision of the director as an auteur, seen in Theodoros (Theo) Angelopoulos’ Reconstruction, (his acclaimed debut), Daminos’ Evdokia, and Voularis’ The Engagement of Anna.

This new wave of Greek cinema identified with the leftist ideological movements felt elsewhere in Europe. These films provided an alternative voice during the years of the dictatorship (1967-74), through symbolism that escaped the notice of the censors. However, this more obscure approach alienated much of the public; coinciding with the rise of television, this was unfortunately timed. A public of avid cinema goers soon abandoned the theaters and isolated themselves in their homes with their TVs and VCRs instead.

By the 1980’s, this had become a crisis. In an effort to compete with television and draw people back to cinemas, films were made that returned to more accessible themes and which tried to capture the lifestyle of the era. The effort met with some success, with box office sales again approaching the levels they had seen in the early 1970’s.

By the 1990’s, some young directors, like Goritsas, Kokkinos, Hoursouglou, and Grammatikos, start making films that express their own unique visions and aesthetics, bringing about a “Cinematic Greek Spring.”

Other developments would continue to make the world of film more accessible to new Greek creators such as advances in digital technology lowering costs, an interest in new themes, and a constructive dialogue with television. European funding from organizations such as Eurimage and Eurofund opened even more possibilities for independent voices. In the last exhibition room of the journey, we see segments of engaging works of recent years, including, movingly, the final work of one of Greece’s most interesting contemporary directors: The Sentimentalists, by the late Nikos Triandafyllidis.

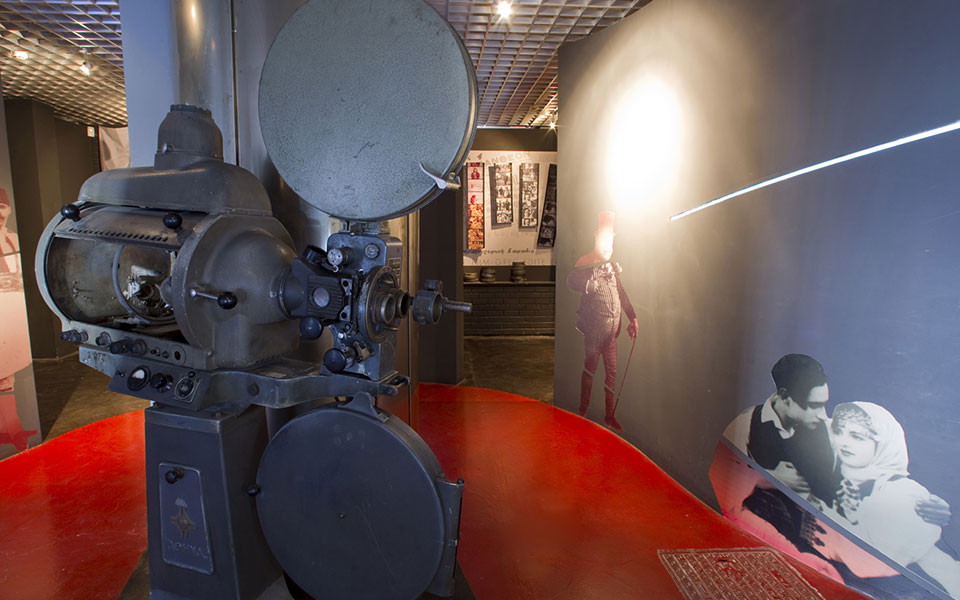

The museum offers a complete, atmospheric engagement with Greek cinema in every aspect, through its diverse displays. Cameras, projectors, reels, and other pieces of equipment are on display, as are awards, costumes, and posters for films. The museum also houses archival collections of films, newsreels, animations, documentaries, silent films, educational films, trailers and advertisements, as well as books and journals.

The HELLAFFI collection of giant hand-painted cinema posters is here, as are the collections of Nicholas and Catherine Bililis, Vasilis Papadopoulos, the Ministry of Macedonia and Thrace, and others.