What’s Really Happening in Messinia?

The Olympic elite, Hollywood’s finest, the...

We know a great deal about the fire that broke out in Thessaloniki in August of 1917, at the western edge of the upper town. We know there was a drought, and, to complicate matters further, that the water in that part of town was diverted to soldiers of the Allied Army of the Orient quartered nearby. That made it easy for a strong wind to spread the fire unchecked over dry land. Huge stretches of the city were gone overnight, and nothing would ever be the same again.

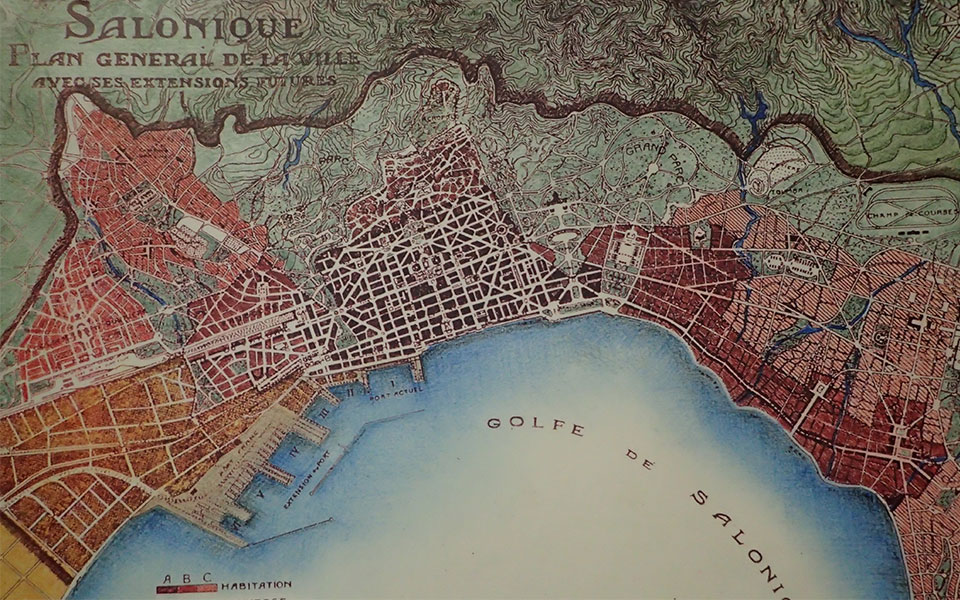

It was a great catastrophe, but also a transformative one. Ernest Hébrard – the French urban planner, architect, and archaeologist – was engaged to redesign the city, much of which would need to be built from scratch. Twisted alleys were gone, and grand boulevards came in their place. The new city was arranged on a grid, following a rational plan. The city gained a beautiful plaza on the sea – Aristotle Square. And, in the attempts to continue Ernest Hébrard’s plan to the north of Aristotle Square, the Roman Agora was discovered and excavated, returning to the city a lost part of its soul.

This transformation has been the focus of much of our attention. But what of the fire itself? What was it actually like? The facts and figures alone indicate the tremendous trauma of the event: the places of worship that were lost (16 synagogues, 12 mosques, 3 churches), the number of homeless (nearly 75,000), the buildings that burned (9,500).

But to grasp the enormity of the event, you need not just numbers, but an emotional connection. Now, a powerful installation at the Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace engages our empathy, and our imaginations, in a deeper way, through sound.

‘The Soundscape of the Fire: Echoes from Thessaloniki of 1917’ is a dialogue between history and art, featuring a audio installation based on historical sources. Emotionally, it’s also a dialogue between us – the listeners living a century after the fire – and the people of Thessaloniki who lived through the event.

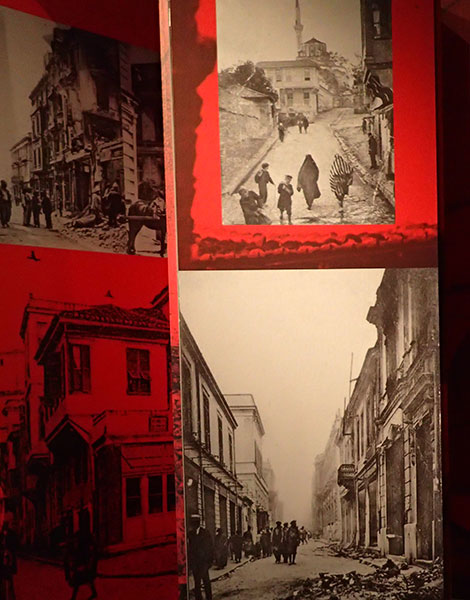

The event takes place in its own building, in the garden of the museum. In the foyer there is an orientation – a description of the creative process involved, and also a pictorial representation of the basic facts of the fire in numbers – the hours it burned, the destruction it caused. The central room, where we hear the soundscape, is lined with photos taken during and after the fire (one of them enormous) in order to immerse us in the scene. But this is just the setting; the primary experience is acoustic.

Sound artist and composer Dimitris Bakas has created it using field recordings (recordings of real sounds and places). In the absence of recordings from the time, the soundscape is an imaginary one, but deeply authentic in its dedication to capturing and expressing the event. His composition Fire of 17 is about 9 minutes long and has three parts – a kaleidoscope of sounds that evoke the pre-fire life of the city, the more traumatic soundscape recreating the experience of the fire itself – flames, water and distant explosions; and a post-fire soundscape consisting of the sounds of reconstruction over-layered with recordings of personal accounts.

Having been immersed in the enormity of the incident for several minutes, these accounts resonate deeply. One man recalls the buildings falling one by one, engaging our senses even further as we imagine the smells. “First it was the storehouse with the oil that went, then the storehouse of the sugar, then the house of so-and-so…” Another man recalls his father describing how they had thought of putting his sister’s dowry down the well, in hopes of saving it. Hearing these voices across time further humanizes the catastrophe. The whole experience is a rare opportunity to engage emotionally with the past, to symbolically experience, however briefly, the enormity of the event.

The last room gives us a place to reflect – there is a large print out of Hébrard’s plan so we can see what, in fact and in theory, would come next.

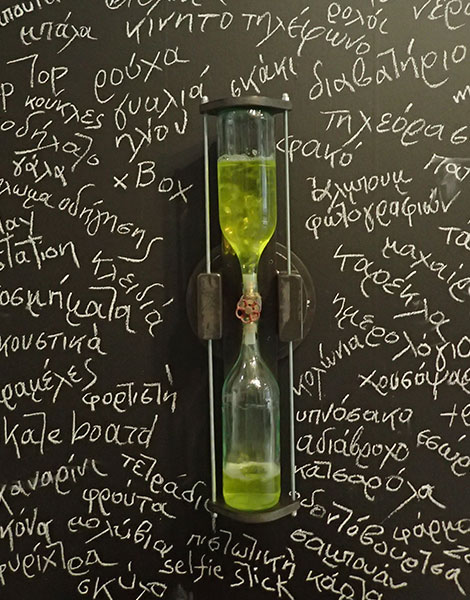

The museum hosts many school groups. Towards the end there is a chalkboard inviting answers to a probing question: “And if it happened to you? If the fire was approaching, what would you take, in a minute and a half?” Among their answers are skateboards and parakeets, diaries and jewels. It gives us a minute to ponder all the precious, personal things that were lost.

The exhibition will be on until June 10, 2018.

Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia-Thraki

68 Vasilissis Olgas (take the bus numbers 5, 6 or 33 to the stop “Laographiko Mouseio”- it’s 5 stops from the White Tower)

Every day except Thursday- 9:00 – 15:30, and Wednesday 9:00 – 21:30

Admission 2€, 1€ reduced.

Tip: The museum has a very charming garden café.

The Olympic elite, Hollywood’s finest, the...

From postmodern bougatsa to wood-fired pizza...

From the fall of a monarch...

Trace St. Paul the Apostle’s journey...