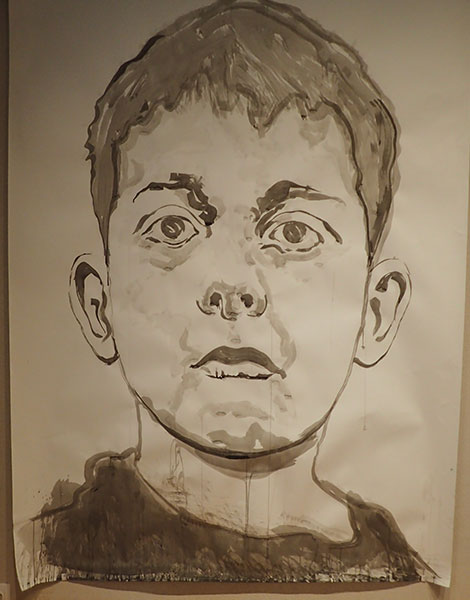

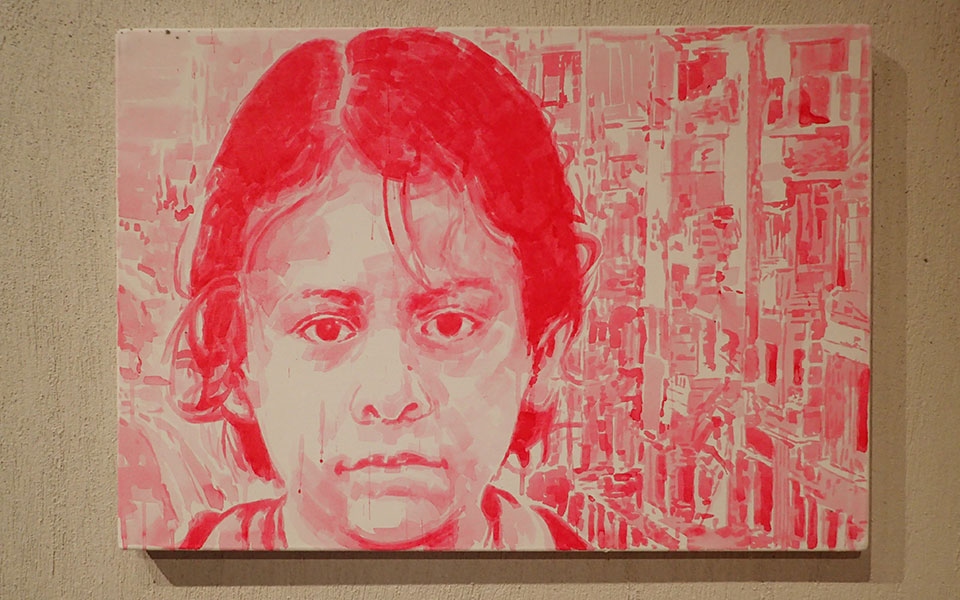

In “Human Geographies,” Nassos Chalkidis exhibits portraits of young Syrian refugees in Greece. Chalkidis’ portraits are large scale – more Chuck Close than Rembrandt – with faces often taking up enormous canvasses. They force an intimacy with their subjects.

We were able to talk to him about his art and his inspiration.

What is your primary motivation when you make a painting?

Greece. Greece, its people, the challenges we face together as a society, and how we face them, the impact these challenges have had on us, individually and collectively. Not least, the moments of transcendence – the strength of character.

This then is how you come to portraiture…

Yes. In my earlier work, I painted spaces – markets, stations, factories – the presence of people is felt just as strongly in absentia. But anonymous people, not individuals. Then something happened that changed my focus to the people themselves – specific people.

Could you share that with us?

A story of a woman here in Greece that I read. She had adopted several children on her own, creating a family from scratch, out of nothing but love. I had to meet her and her beautiful family; once I met them all, I had to paint them. That changed the course of my work.

Info

“Human Geographies,”

At the Arsakeiou Stoa (upper story), 47 Panepistimiou St, Athens.

March 19 – April 2, 2018

© Amber Charmei

© Amber Charmei

In describing your portraits, you often use a word that could be considered unexpected: landscape.

A portrait is actually psychological landscape – they reveal things that the subject himself was never aware of. I have found this to be true even in self-portraiture; I sometimes confront aspects of myself that I had not seen before. It’s illuminating.

What is your process?

It’s very hard to paint someone you don’t know – you need, at the very least, a lot of information. But to capture who they are, you need some intimacy, some familiarity. You need to know who someone is, because that is what you are painting – who they are. The image is merely the entrance to the character; you need to go beyond that.

Conveying meaning seems central to your work. How do you see the role of the artist in society?

Artists generally have a heightened sensitivity – certainly to our inner worlds, but also to the outer world. We are not in a vacuum. We’re like antennas – picking up what is going on in society. Art is a reflection of society: a decadent society equals decadent art, a conscious society equals conscious art. As artists, our role is to ask a giant “Why”. And then sometimes we try to answer that question, or at least to illuminate the darker corners, to bring light where it is needed most.

© Amber Charmei

How is that reflected in your current projects?

The refugee crisis made a deep, meaningful impact on us as a society – it awakened our awareness, our compassion and humanity. At least it did at first: then we forgot about it. We were shocked, then we lost our sensitivity and got on with our lives; it has become like the rain. It is ever present in my life though. I am also a teacher in the public school system, and the reception of refugee children into the public schools is a topic that is familiar to me from the inside.

I have a friend who does a lot of work helping refugees through the Center for Hospitality for Refugees in Exarchia, a joint initiative of the Syrian Home and Wilkommen. I visited the center, and the people I met there inspired me profoundly. The children, in particular, were filled with optimism, and that optimism was contagious. These children are part of our new generation; they are going to help bring our culture into the future. That is what I want to paint – the future of Greek society.”

All the proceeds from the sale of this series will benefit the Center for Hospitality for Refugees in Exarchia.