Athens, like most Greek city-states, was ruled early on (7th c. BC) by aristocratic families, who held most of the power, thanks to their wealth and the control they exercised over religion. Eventually, most cities limited the powers of the aristocracy, not unlike the gradual erosion of the authority of the House of Lords in England.

The transition was frequently spurred by the rise of an individual set against the aristocrats, often with popular support. This individual was termed a tyrant (tyrannos), a word which meant he seized and held power unconstitutionally, but did not refer to how he wielded that power.

Over time, the word picked up all the negative connotations associated with it today, but early on this was not necessarily the case. Here is Thucydides’ account of the tyranny of the Peisistratids in 6th c. Athens:

“Indeed the Peisistratidai carried the practice of virtue and discretion to a very high degree, considering that they were tyrants; and although they exacted from the Athenians only five percent of their incomes, not only had they embellished their city, but also carried on its wars and provided sacrifices for the temples. In other respects the city enjoyed the laws established before, except insofar that the tyrants took precautions that one of their own family should always be in office.”

It is hard not to approve of someone who maintained infrastructure, built temples and aqueducts, ran a successful defense department, and still expected to collect only a 5% tax every year. One has to believe that, had there been an election, such a candidate would have won easily.

Perhaps inevitably, tyrants overstepped the bounds. A common mistake was to try to establish a dynasty, and nowhere in Greece did tyranny as an institution last beyond the third generation. Despite genetics, the offspring often lacked the wisdom, charisma, or vision of their fathers, and the city states turned to new forms of government. The first to develop and implement that form called democracy was Athens, late in the 6th c. BC.

The creation of the Athenian democracy was a process, not an event, though the focus has often been on the reforms of a little-known individual named Cleisthenes, who in 507 BC began the erosion of aristocratic control based on clans and geography by assigning all Athenians to a newly-created group of tribes (phylai). Citizenship and most political, military, and social activities were henceforth controlled by the tribes, thereby undercutting the earlier authority of the clans and creating a semblance of equality. There were, however, important changes made by other leaders, both before and after.

Earlier in the 6th c. BC, Solon had created courts where jurors and judges were chosen from all Athenians, not just from aristocrats or magistrates, which had previously been the case. As in the American system, the judicial branch had final say over executive and legislative actions, and juries of the people were the bedrock on which democracy was founded.

In promoting Athenian naval power, Themistocles changed the political landscape of the city early in the 5th c. BC. The tens of thousands of rowers who manned the fleet that carried Athens to preeminence expected – and were granted – a greater share of power, which came at the expense of their social superiors who made up the smaller land army. This change broadened access to political power considerably.

Political power is a fine thing, but only if one can afford to wield it. By the 5th c. BC, Athenians were paid to sit on the council and assembly, or on juries, so the poorer citizens could actually afford to participate in the political life of the city. Pericles was influential in this final necessary step leading to democracy.

With modern democracy in disarray following the results of elections in the US, Turkey, the UK and a number of other EU countries as well, it is worth considering whether some aspects of government were handled better in antiquity than today. When we think of the differences between ancient Greek democracy and the modern version(s), several things stand out.

In most modern democracies, women usually participate fully, both in voting and holding office. In antiquity, women had no public role, and resident foreigners and slaves were not allowed to participate, either so the percentage of the actual population that shared in Athenian democracy was rather small.

Electing officials is, of course, a fundamental feature of modern times; that is another major difference. In Athens, there was a much greater reliance on the “luck of the draw” than on election. Sortition, or allotment, was the preferred means of picking most public officials and deliberative bodies in Athens.

At first glance, that may seem odd, and yet we should ask ourselves: if we pulled 535 names out of a hat, could we do worse than the fractious, entitled, and ineffective congresses that US elections have brought us in recent years? To be sure, there might be 50-odd wackos on the left and 50- odd wackos on the right, but in the middle there would be a large majority of individuals from a cross-section of American society, trying with good will to make useful, necessary, and effective laws. In theory, at least, common sense and fair play would have a far better chance of prevailing than at present.

There are, however, a few positions too important to leave to the luck of the draw, no matter how thorough the Athenians wanted their democracy to be. You need competent generals to run an army, and you need trained bookkeepers to serve as treasurers, so these officials were elected in Athens.

The third position, perhaps less obvious, was the water commissioner, because managing water is essential to mankind. In this respect, my wife has often repeated her acute observation that, if a nuclear holocaust does occur, it makes no sense to hide away the 500-plus Washington-based lawyers of Congress; what we will need when survivors crawl out of the bunkers is 500 plumbers, capable of providing water, removing waste and resurrecting a healthy society.

We speak of “Periclean” Athens or “Periclean” Democracy, and yet Pericles was never the Eponymous Archon, the top official in the state, after whom each year was named. He was, instead, repeatedly elected general of his tribe, which allowed him regular access to the council (boule) and assembly (ekklesia), while demonstrating his popular appeal with at least a segment of the population. In this way, he could show his competence in leadership – much like our governors, who have a record of executive action in office demonstrated by running a state, that is, a segment of the population.

Others, of course, could display their competence as well. In Athens, there were few or no professional politicians and the citizens themselves were expected to participate: to “rule and be ruled in turn,” as the phrase goes. The allotment of offices was facilitated by elaborate kleroteria, machines designed to ensure that the draw was fair. These machines were also used to pick the large juries with which the Athenians filled their courts, with a minimum of 200 jurors.

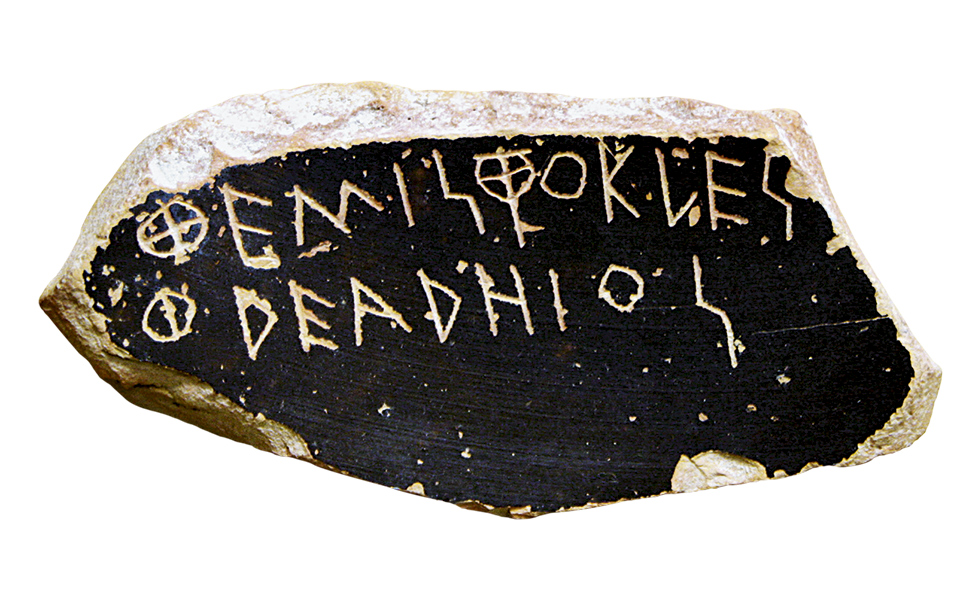

Strict and effective term limits were also a given in Athenian politics, as was accountability. Except for a few organizers responsible for the big festivals held every four years, all other officials, including magistrates, members of boards and commissions, senators (bouleutai) and jurors were expected (and allowed) to serve only for a single year at a time. Incoming officials were examined before taking office and were also expected to render full accounts at the end of the year. What’s more, each year it was possible through ostracism to remove any one individual from both public life and the city for no less than 10 years.

Democracy today, as in antiquity, remains a process; changes in society and technology require revisions as to how we govern ourselves. The concept of full and equal citizenship, a sense of wishes and values of the people, and an understanding of the privileges, rights, and duties of the individual are all part of striving for the best political system. It cannot hurt to look back and consider the past as we prepare for and move into the future.

John McK. Camp II is Stavros Niarchos Foundation Professor of Classics at Randolph-Macon College, Virginia; he’s also Director of the Athenian Agora Excavations and author of many books on ancient Greece.