Why Volos is Perfect in Autumn

The charming port city of Volos...

Merging into a single sculpted mass, roofs in Mandraki await the autumn rains to catch precious water and direct it into private cisterns.

© Clairy Moustafelou

The towns of Nisyros typify Greek Aegean settlements, with houses clustered close to each other for shade and protection from the strong Aegean winds. Streets wind along natural topographic boundaries for convenience, occasionally parting to create squares (plateíes) where churches, chapels and other public buildings are situated.

Churches tend to be cross-vaulted basilicas influenced by the Latin church type introduced to the Dodecanese by the Knights of St. John. Chapels are modest barrel-vaulted structures, hidden from view to evade detection by pirates, and sometimes excavated from rock outcroppings. Other public buildings include the Town Hall (Dimarcheío), the Port Authority building (Kazérma), the island’s schools (scholeía), and the Public Thermal Baths (Loutrá) at Mandraki. These all show strong neoclassical influences, having been built in periods of heightened national sentiment and expectation of union with the Greek motherland.

Exposed stone is fashionable once again

© Visualhellas.gr

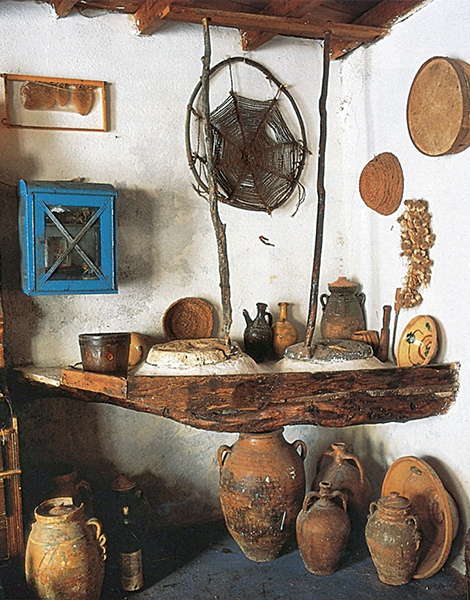

A double hand-mill in Mandraki.

© Cornelis De Vries/Melissa Publishing House

The typical Nisyrian house is a two-story building (dípato or anokátogo); sometimes it is a single-story (monópato) and more rarely a three-story (trípato) structure.

The ground floor is known as the katóï, while the upper floor is called the anóï (from the ancient words “katógeion” and “anógeion”). The third story is referred to as the órofos, and appears occasionally where the property area was not sufficient to accommodate the tenants on two levels.

Houses are simple four-sided boxes, conforming to property boundaries, with the occasional projecting terrace or appended exterior stairway. They are built of medium-sized rubble stones held together with lime mortar; in olden days, they were left exposed and unpainted. In the early 20th c., it became common to plaster and whitewash the façades in the manner of Cycladic vernacular buildings, but exposed rubble stone is now fashionable again. Most houses are accessed from the street, the entrances occasionally being elevated a meter or so off the pavement with the presence of stepped stone platforms (pezoúles) to protect the ground floor from rain water and facilitate the unloading of pack animals.

Some buildings are entered by way of courtyards (avlés) at the front or on the side of the principal façade. Subtle differences are noticeable in the houses of the three principal towns. For instance, the structural arch is used more commonly at Emporios; in Nikia, houses have tiled, lean-to roofs; in Mandraki, the thrápfa, or roof stair-tower is common. In general, however, the plan arrangement follows the same principles.

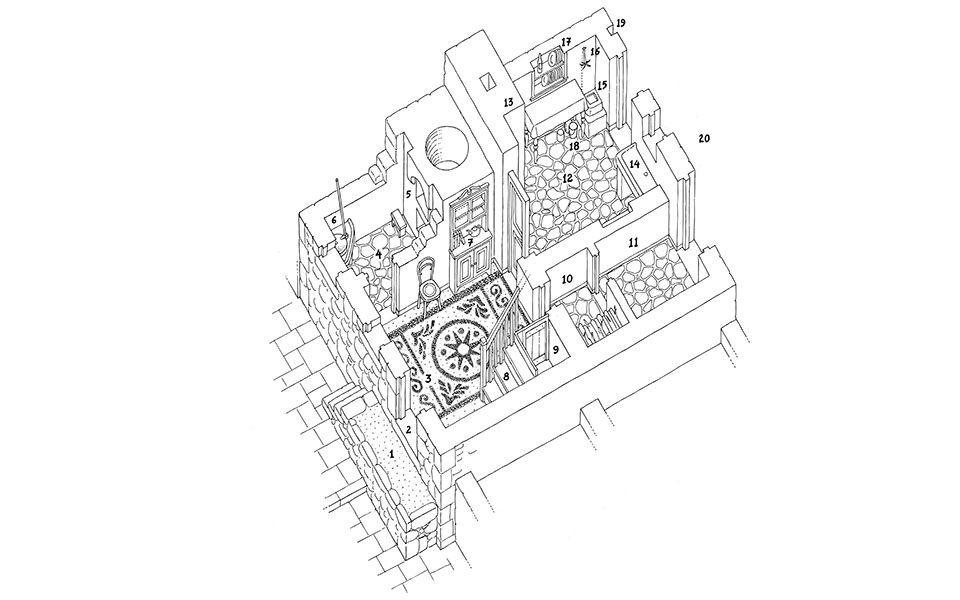

THE MOST CHARACTERISTIC ROOMS AND FURNISHINGS OF THE NISYRIAN KATOΪ: 1. Stepped landing 2. Entrance 3. Entrance hall 4. Baking room 5. Oven 6. Hand-mill 7. Buffet 8. Staircase 9. Storage 10. Storage room (now usually a bathroom) 11. Place for hay and small animals 12. Kitchen 13. Fireplace 14. Sink 15. Cistern 16. Grappling hook 17. Dish-rack 18. Water bucket 19. Downspout 20. Courtyard

© Cornelis De Vries/Melissa Publishing House

Because of the tightness of space in the settlements, home builders typically arranged spaces in opportune ways, and it is difficult to identify a single dominant plan type. However, certain rooms were common to all houses. For instance, most ground floors incorporate a multi-purpose living space, the katóï, and a cooking space called the maerió (from the ancient “mageireíon”). In older times, the katóï and maerió floors were made of compacted earth or clay, or occasionally pebble mosaics.

Beyond these rooms in the back of the house are two or more smaller spaces communicating directly with the court or avlí. These are the achyrónas for storing hay (which also doubles as the aoumás, or shelter for small animals), and a kellí for storing wood. There’s nearly always a small room with an oven opening onto the katóï, which is called the fournarió. Here one usually finds the cherómylos, or hand-operated mill, consisting of two flat stones where grain was ground in preparation for the oven.

All of the older houses contain a wooden sleeping platform called a moní, which is elevated about 1.20m off the floor. Though usually located upstairs, this feature is also occasionally found in the katóï. It is separated from the rest of the living space by a transparent latticed curtain (the amoussía). The sleeping mattress (stróma), which in older days was filled with hay, is kept covered during the daytime with decorative embroidered sheets known as ploumisménes sendónes. The bed is accessed by stepping on the pángos, a long wooden box located at the foot of the sleeping platform, which is used to store sheets and a clean change of sheets.

Sometimes a series of vertical, ladder-like steps are built against the moní, rising between two vertical posts that serve as rails. The closet-like space beneath the moní is called a kellári, and serves as a pantry. Directly above the door to the kellári is the moussándra, a small wooden platform built even higher than the level of the moní. This is where small children sleep, close to their parents behind the amoussía, and protected by a wooden parapet.

New pebble mosaic pavement in Mandraki by Nisyrian craftsman Dinos Papadelias, who has once again popularized the technique.

© Cornelis De Vries/Melissa Publishing House

In one corner of the cooking area, or maerió, is the fireplace (záki or tsimniá), where foods are cooked and a fire tended for warmth in winter. This consists typically of a lower compartment where the wood is kept, and an upper estía, or hearth, which communicates directly with the flue.

The sink (pinakoplýtis or anerádos) is normally located close to the fireplace; in earlier times, ash was used instead of soap for cleaning. Against the wall of the cooking area is a round wooden table-top, the soufrás, which can be stacked vertically out of the way between meals. The cherómylos (or hand-mill) is made of two round flat sections of volcanic stone (the upper panópetra or panáris and the lower katópetra or katáris). The panópetra is turned with the help of a stick which is secured to the ceiling.

Sometimes the katóï is built directly over a cistern (vistérna), the round mouth of which (tráchilas) is constructed of stones and mortar and covered with a stone slab or wooden plank. The cistern is essential to all houses on Nisyros, as the island lacks natural springs. In the more densely-built parts of town, wooden staircases are incorporated indoors in the katóï, usually facing the principal entrance. The space underneath the stair here serves as the equivalent to the kellári, or pantry.

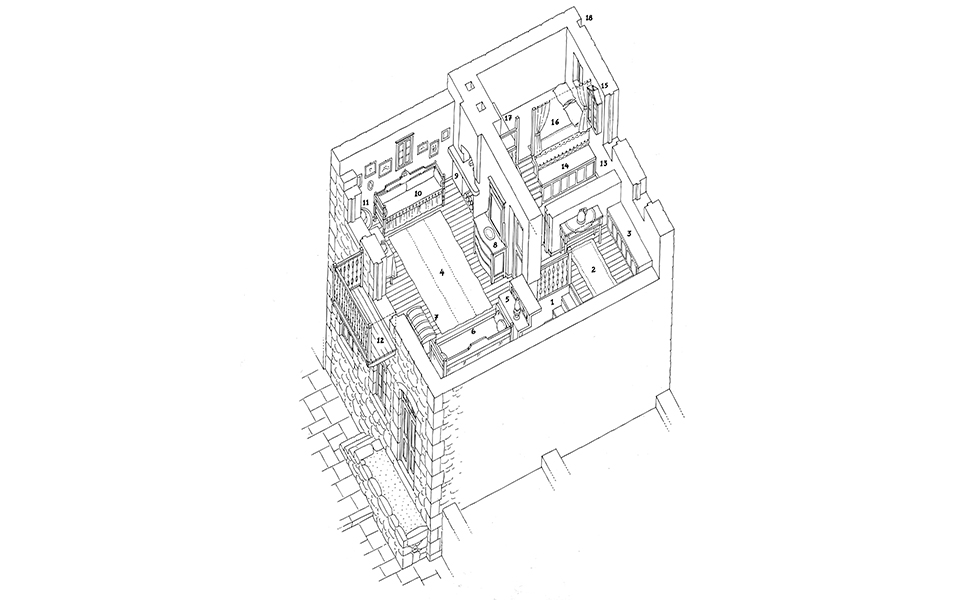

THE MOST CHARACTERISTIC ROOMS AND FURNISHINGS IN A NISYRIAN ANOΪ: 1. Staircase 2. Hallway 3. Bench/chest 4. Living-room 5. Stair-box 6. Sofa 7. Chest 8. Dresser 9. Fireplace 10. Sofa 11. Brazier 12. Balcony 13. Bedroom 14. Bench/chest 15. Icon stand/wedding-wreath display case 16. Sleeping platform 17. Elevated infant’s bed 18. Downspout

© Cornelis De Vries/Melissa Publishing House

The upper floor of Nisyrian houses typically consists of a large public sitting room (sála), which occupies the entire front of the building; a smaller room (kámari) used for storage or for the loom (argaliós); and a long private room (the mésa kámari) on the back side, which served as the principal bedroom.

There are numerous variations on the way one reaches the first floor of a Nisyrian house. In general, houses in more built-up areas of town incorporate a wooden staircase within the katóï, placing it near the entrance. In such cases, one ascends directly into the kámari or a small hallway. A common feature is the glavaní, a raised and stepped built-in hollow box in the room directly over the staircase, which affords more headroom over the stairs. In some houses, there is an exterior stone stair that rises to a landing over the entrance to the ground floor (the domátsi in Mandraki; páno avlí at Emporios; and xáto at Nikia), from which one attains the sála and other upper-floor rooms.

Nisyrian houses often incorporate small, brightly painted wooden balconies (usually around 1x2m), accessible from the sála, which double as places to keep dry foods and laundry. Their sides are made of closely-fitting vertical planks (katonákia), supported on a row of cantilevered timber beams.

The charming port city of Volos...

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

A journey through Hania’s Venetian past,...

Charming architecture, unique beaches, rich history,...