The Many Gazes of Little Miss Grumpy

Illustrator Maria Pagkalou draws enchanting portraits...

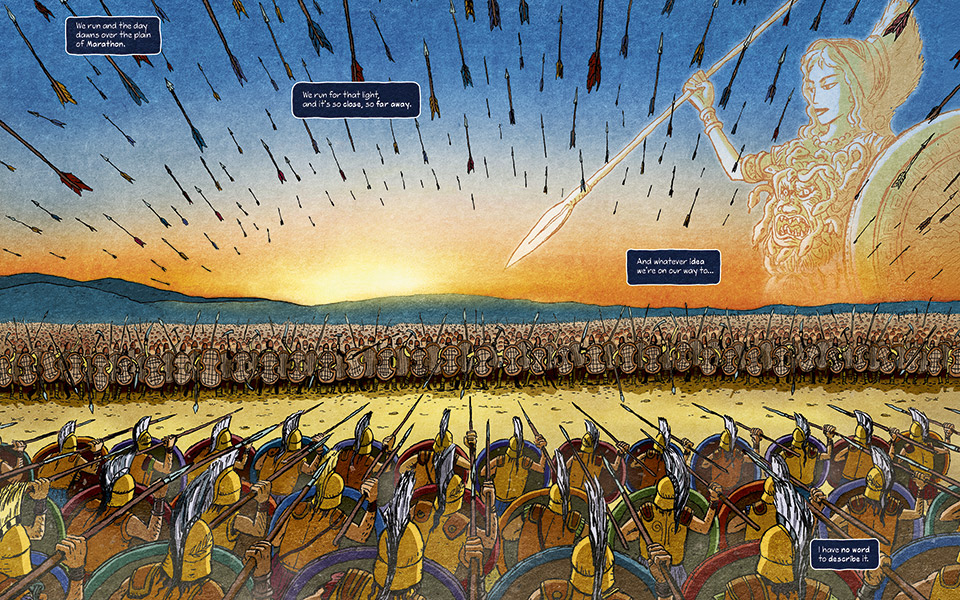

A scene from the hit graphic novel Democracy

© Pictures & Hues: Alecos Papadatos & Annie Di Donna

The goddess Athena, sprung fully grown from the split skull of her father Zeus, was literally a child of thought, much like the city under her patronage. Athens grew from an idea that Athenians had of themselves, an idea that made them different from citizens of other city-states. Democracy, the concept that changed the world, and our graphic novel of the same name (a novel which charts the story of the concept’s birth) are in their separate, yet interlinked ways, both children of thought as well.

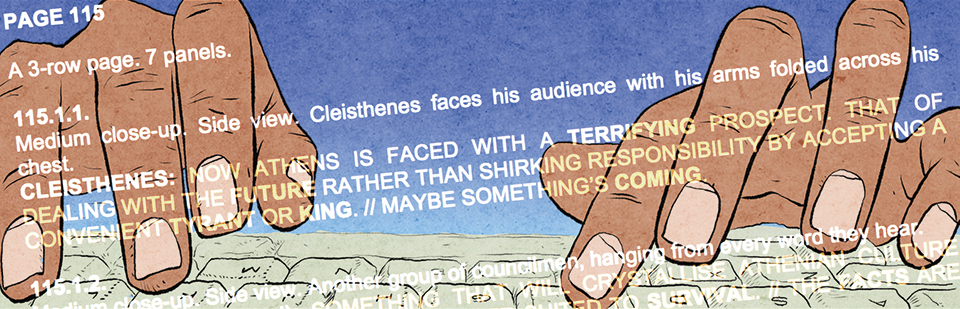

The serendipitous quality of this pattern grows more intricate when one bears in mind the fact that the novel originated with Alecos becoming intrigued by his daughter Io’s research for a school project on the reforms of Cleisthenes, and one considers, too, that so much of the story deals with fathers and their offspring (as well as with Athena herself). It all comes full circle with our decision to dedicate this “offspring” of ours to our fathers.

It seems that what goddesses, cities, political systems and graphic novels share most of all is that they are birthed into being, and that the labor pains are never trifling. In a graphic novel, the work of a wordsmith, much like that of an artist, is wrought with the kind of loneliness experienced by gods and long distance runners. Alecos, Annie and I toiled alone at our tasks, separated from each other; in their case, it was by a table’s distance, in mine it was by some 300 kilometers or more.

A graphic novel script, written in a manner similar to that of theatrical plays and film scripts, is crafted the same way gods create worlds and runners get through races: word after word and inch after inch, with a grandiose plan and painstaking perseverance, every detail and texture included, and with the end of the road always so far away.

Abysmally imperfect for godhood and painfully out of shape for any serious athletic pursuit, the writer struggles towards the birth of the script, at which point suddenly another labor begins, that of the artist. Alecos and Annie had to hit the ground running, and decipher and interpret what I indicated, not just in terms of dialogue, milieu and action, but in mood, atmosphere and emotion as well. Imagine a cinematographer who has to double as a film’s director and editor and transcribe a flawed would-be-god’s gibberish into a flowing, coherent message (much like our Pythia in Delphi), all the while in a race to the finish line – the dreaded deadline. Oh, and add to this the exertions of research, from stacks upon stacks of books, articles, treatises and studies on every aspect of a world long gone to actual location scouting and photography – Delphi was Alecos’ assignment, the Acropolis was mine – and the degree of difficulty becomes clearer.

“The three of us have stated on numerous occasions how we believe democracy is still being created every day, with each decision, each forward step or backward fall its citizens take, and that belief dominates our graphic novel.”

The creative process: an original illustration by Alecos Papadatos and Annie di Donna.

“Our everyman protagonist, an artist and a storyteller, became the incarnation of not just us, but of the everyman of then, now, and all the ages in between.”

However – and this is not just a trait of graphic novels, but of any collaborative storytelling worth its salt – the loneliness of these labors is preceded and interrupted throughout the long period of gestation by that most democratic of all concepts: dialogue. The telephone and the internet provide modern storytellers with a variety of ways to communicate and engage in hours of back-and-forth, but in the five-odd years from the book’s start to its finish, we’d also get together in Athens and brainstorm over each chapter and scene before, during, and after its writing.

We’d do it in the way that comes easiest to friends who are co-workers, over coffee or food and drink. It is the table, not the desk, where a collaboration is best forged. At small cafés in Plaka, tavernas tucked away in the bystreets of Thiseio, or bookstore cafeterias a stone’s throw from Syntagma Square, we’d break down the story, experiment with form and theme, and tussle with how to turn ideas – the storytelling kind as much as the grand philosophical kind – into narrative.

All the time, the Acropolis was there in the background or just out of view, still with us after all these millennia, not just to link us bodily with Cleisthenes and Leander and the past, but to remind us of that other dialogue going on, the one between yesterday’s history and today’s interpretation. And this, gentle readers, turned out to be the most arduous and important aspect of this book’s birth. We had to do justice to what had happened then, respecting historical sources and facts and the differences of cultures separated by far more than just thousands of years, but we also had to fill in the dots and gaps, negotiate the variances in the interpretation of even the simplest facts, to make the events of then understandable to all of you living in the here and now. Our 21st century worldview filtered the politics of 510 BC. Our everyman protagonist, an artist and a storyteller, became the incarnation of not just us, but of the everyman of then, now, and all the ages in between, trying to fathom, react to, and survive the systems, policies and circumstances that turn individuals into pawns, twist ideals into propaganda and make the birth of something new into the death of a dream.

“We’d get together in Athens and brainstorm over each chapter and scene before, during, and after its writing. We’d do it in the way that comes easiest to friends who are co-workers, over coffee or food and drink. It is the table, not the desk, where a collaboration is best forged.”

This process which went into the making of the book became the book itself, in plot and theme, imagery and nuance. How well we achieved that is up to you to judge, but that was always our point. The three of us have stated on numerous occasions how we believe democracy is still being created every day, with each decision, each forward step or backward fall its citizens take, and that belief dominates our graphic novel. It is all part of a society’s labor pains, to paraphrase our Cleisthenes. The hope of a successful birth encourages going forward with it, though the cost is often dear.

For artists and storytellers, there is a measure of comfort in knowing it all comes to an end of sorts at least, when the book is finally taken off our hands by the goddess of deadlines – for it’s not quite ready, it’s never, never quite ready – and given to you, the readers, to engage with and judge and struggle over, to grapple, understand, misunderstand, cheer or rail against.

But just as the end of our labors is the start of yours, so too for Leander, poised forever at the plain of Marathon, for Athens, still going on in the face of new adversity, and for democracy, whether abolished or upheld, evolved or twisted beyond recognition, it never really ends. Democracy, its story and its state, is always in the making.

“DEMOCRACY” by Alecos Papadatos, Abraham Kawa and Annie Di Donna is published by Bloomsbury.

Illustrator Maria Pagkalou draws enchanting portraits...