“Architecture shows us how people lived on Earth until they died. Anyone who knows how to live, knows architecture and what we seek from life is expressed in the way that we do architecture. Let us learn to be simple, to live and build sparsely, without superfluous ornamentation, without palaver and without all the extra weight that we don’t need at all. Let us strive for a life that is simple, clean and bright, just like the architecture we build for its sake.”

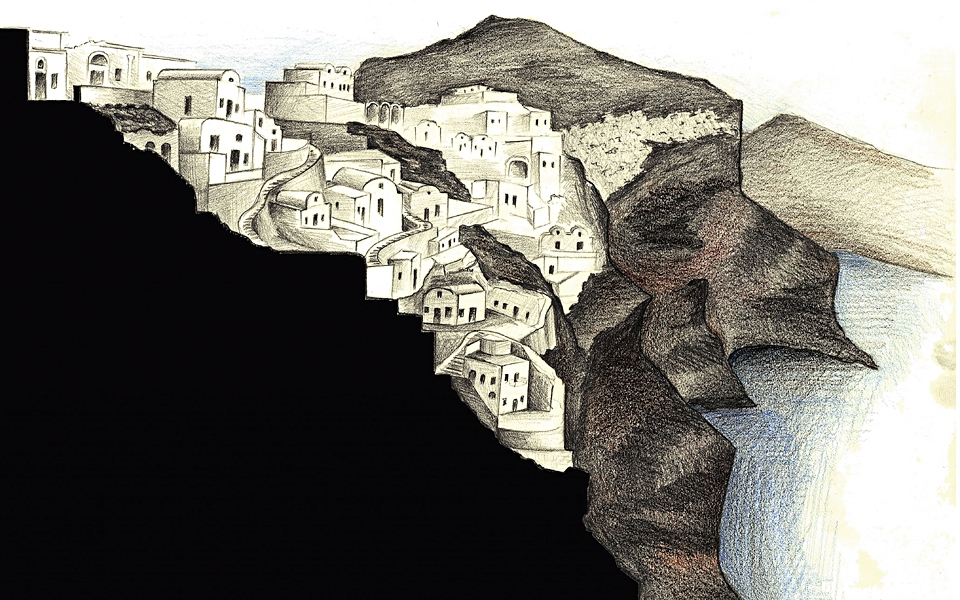

These are the guiding principles of the celebrated Greek architect Aris Konstantinidis (1913-1993) as outlined his book The Architecture of Architecture, and it is impressive how this description appears to apply so perfectly to Santorini. From prehistoric Akrotiri (built on the coast and protected from the strong northerly winds but also stretching inland, thus benefiting both agriculture and fishing) to the amazing yposkafos (‘dug into the rock’) homes we see in Oia today, the architecture has been fully adapted to the particular conditions on the island and has catered to the needs of its people throughout the ages.

It is believed, for example, that the first residences to be hewn out of the caldera’s rock face appeared in the 7th century to protect locals from the Arab raids that were ravaging the Mediterranean. Safety continued to be a key concern throughout the Middle Ages and up to the 18th century. Residents had to find ways to protect themselves from pirates, and the architecture of that time is largely of a defensive nature. The construction of fortified castle-towns, known as kastelia, began in the 14th century at Skaros (present-day Imerovigli) and Aghios Nikolaos (Oia), followed later by Pyrgos, Emborio, Akrotiri and Panaghia (Fira).

“Let us strive for a life that is simple, clean and bright, just like the architecture we build for its sake.”

On the cone-shaped rock of Skaros you can still see some traces of the fortified tower of Goulas and a castle that survived Turk and pirate raids throughout the Venetian occupation, but was severely damaged by the eruption of the volcano off the beach of Koloumbo in 1650. All the castle-towns were abandoned by the mid-18th century, as the threat of pirates waned and the people began feeling constrained behind their thick walls. They struck out to parts of the island that had been off-limits until then and started laying the foundations of the residential developments we see today. We have an excellent idea of how the island was at that time thanks to a map made in 1801 by French entomologist and traveler Guillaume Antoine Olivier, held today by the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Library.

The locals had limited funds with which to build, however, and most constructed their homes themselves – occasionally employing unskilled labor to help – looking only to create adequate shelter without much concern for architectural or aesthetic style. Even so, the prevailing social, financial and geomorphological factors contributed to the creation of a charming style of architecture that is still very alluring.

Architecture started becoming more sophisticated in the early 20th century as the island’s population became richer, thanks to agriculture, shipping and commerce. The nobles and sea captains were in a position to build homes that would reflect their economic and social status, drawing inspiration from Europe’s Renaissance and neoclassical architecture and using skilled workmen and expensive materials. This newfound wealth is also reflected in the public buildings and churches of the time. However, even these “foreign” buildings blended harmoniously with the landscape and the island’s unique urban fabric, never striking a discordant note.

THE MATERIALS

How do you build anything, from the humblest home to the most opulent mansion?

You start with the materials available at hand, and Santorini has a wealth of such gifts, thanks to the volcano.

The black igneous rock is hard and extremely tough to temper, so it has been used mainly for walls.

The island’s red rock is seen mainly in domes and arches, while chunks of pumice proved ideal for smaller rooms built above archways.

The ground pumice, however, is by far the most important material. It holds together well and, when mixed with lime, makes a very durable mortar. For decades, this was a major export and has been used in such major projects as the Suez Canal and the ports of Alexandria and Istanbul. Rising demand led to quarries being opened in Oia, Fira, Akrotiri and Thirasia, though these closed in the 1980s.

Found in abundance in the soil, this pumice allowed locals to dig deep into the landscape without fear of rock falls.

THE BUILDINGS

YPOSKAFOS

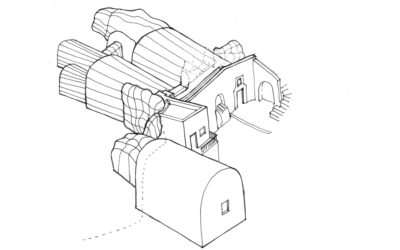

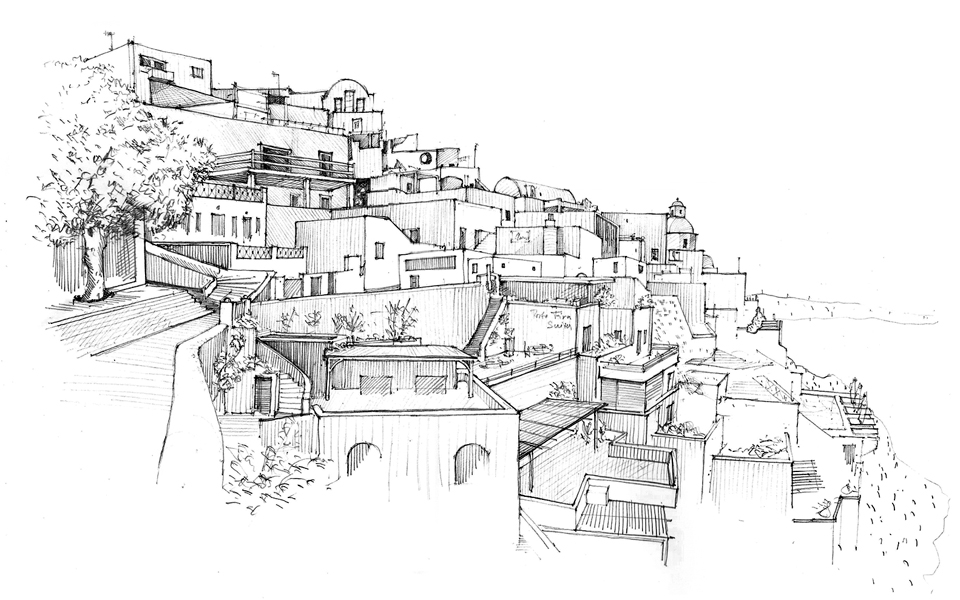

The Santorinians built their houses into the volcanic rock, creating entire villages nestled into the island’s cliffs. Most of the yposkafos are along the brow of the caldera in Fira, Oia and Imerovigli, but there are also examples in once-fortified settlements like Pyrgos, Emborio and Akrotiri. In Vothonas, Finikia and Karterado, construction followed the streambeds, and homes were build into their steep banks. An yposkafo can be a dwelling that is dug entirely into the rock or one with exterior additions that are usually covered by a dome.

They tend to be quite narrow and deep, with the living room at the front, bedrooms in the back, a tiny kitchen tucked away off the main living area and a bathroom placed outside the house proper, usually on a corner of the balcony or courtyard. Following the natural lines of the caldera, the houses face south and west, while their horizontal arrangement means that one home’s balcony is another’s rooftop. The most interesting element of this architecture is the use of domes, which come in all shapes and sizes, and lend a certain sculptural quality to the island’s settlements. Because yposkafos made use of what nature provided, they tended to be built by poorer residents such as laborers, farmers and sailors (Oia has an entire neighborhood built by crewmen).

Kapetanospita

Prosperity came to the island in the late 19th century and so did more impressive homes. Oia was especially popular among the island’s high-ranking maritime officers: in 1890, it had a population of 2,500, a fleet of 130 sailing ships, 13 parishes, a bank, a customs office and a number of small manufacturing firms. Vineyards were planted across its plateaus and Santorini’s famous wine was exported in large quantities, even to France. The shipowners and captains, of course, were not about to start scrabbling through the rock to make their homes, known as kapetanospita or captain’s houses.

They built them in the loftier quarters of Oia and Fira, inspired by Renaissance and neoclassical architecture. Their homes were big and often multistoried; they had spacious courtyards and incorporated many elements of the vernacular architecture, including domes. As an added luxury, they had large tanks to collect rainwater, because drought was and is an ever-present threat on this arid island.

Agrotospita & Canavas

The eastern end of Oia was reserved for farmers; today this quarter is now part of the rest of the village. The main characteristic of these farmers’ homes (agrotospita), usually built on the fringes of the town or even in the fields, was their large courtyards.

Their canavas, the grape-pressing and storage areas that were built underground or into the rock, were also impressive with their arched doorways, large enough to roll big wine barrels through. Santorini used to have canavas all over. In Finikia, in fact, there were as many canavas as there were houses.

The Churches

Santorini’s churches are defined by anonymous vernacular architecture. The island has over 600 churches and chapels, only one-fifth of which are dug into the rock. These are simple, square edifices, mostly done in a sparse white, without any particular ornamentation. There are also a number of larger churches that were built in the late 19th century (like Panaghia Bellonia in Fira and Aghios Georgios in Oia) and designed in the Byzantine and classic Greek styles.

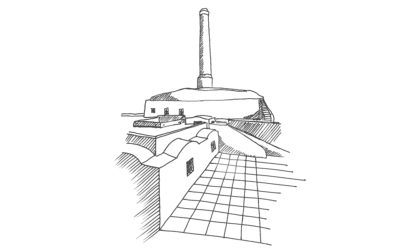

The Industrial Buildings

The Santorini cherry tomato that has become one of the island’s signature products started being cultivated more intensively in the late 19th century. From 1925 until the early 70s, concentrated tomato, along with wine, was a mainstay of the island’s economy. Production began in small cottage units and was later increased, thanks to the development of larger plants that today constitute very interesting examples of small-scale industrial architecture. There were 14 processing plants on the island during the tomato’s heyday. Today, the former Dimitris Nomikos factory in Vlychada has been transformed into a modern Industrial Museum that offers visitors a fascinating glimpse into the island’s modern past. You should not miss a visit to the Gaia Winery on the road between Kamari and Monolithos either, as it, too, is a very interesting example of industrial architecture.