The 30 Greatest Holidays in Greece for 2025

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...

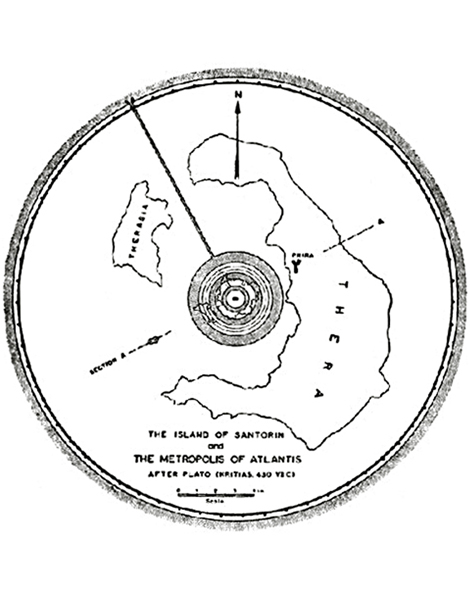

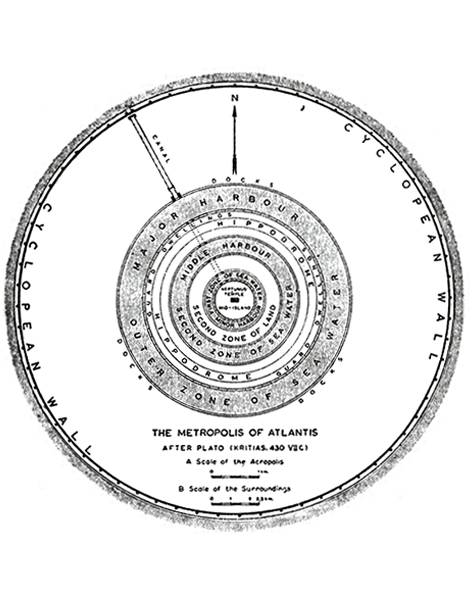

The island of Atlantis, named by Poseidon's first born son, was surrounded by concentric rings, two of land and three of sea, so perfectly round they appeared as if shaped by a lathe

© Illustration Katerina Alivizatou

The gods, it is said, once divvied up the different parts of Earth among themselves by lot so as to establish who owned what and put all acrimony to rest. The island of Atlantis came to Poseidon, who settled it with the children he had sired with a mortal, Cleito. He fortified the small hill that was his home near the center of the island, making it impregnable. Around it, he built concentric rings, two of land and three of sea, so perfectly round they appeared as if shaped by a lathe.

This description is from Plato’s dialogues Timaeus and Critias, penned some 2,400 years ago. In these works, the great Greek philosopher discusses the notion of an ideal state, a Utopia everyone would like to call home. Here we find some 20 pages in which he describes Atlantis. I wonder what the philosopher would have thought if he knew that in those few pages he had created the greatest legend of all time?

No other myth has so excited the imagination as Atlantis, judging from the thousands of monographs, articles, novels and science-fiction works inspired by it. The location of the sunken continent has even come to constitute the object of research for serious scientists, some of whom have launched major search operations across the globe.

A case in point is the 2011 endeavor presented by National Geographic and conducted by a team of US, Canadian and Spanish archaeologists and geologists, headed by Professor Richard Freund of the University of Hartford in Connecticut, USA. Using satellite imagery, deep-ground radar and digital mapping, the scientists located traces of a 4,000-year-old sunken city in a national park north of Cadiz in Spain, near the Gibraltar Straits. They believe this city could be Atlantis and that it was wiped out by a huge tsunami.

Such theories find a fervent audience among Atlantologists, those who believe the mythical city really existed. Among their list of possible locations, we also find the Greek island of Santorini a prime candidate, because of the massive volcanic explosion in 1613 BC that erased a brilliant civilization from the map.

The truth is that there are several similarities between Plato’s Atlantis and Santorini to back the belief. The volume of the volcanic material that was ejected from the bowels of Earth created a massive subterranean crater that swallowed up most of the island, forming the stunning caldera we see today and forever changing the island’s shape, even as a resulting tsunami swept over every island at a distance of 50 to 60 kilometers from the epicenter of the eruption.

While the volcano is believed to have destroyed Akrotiri, the blanket of ash it deposited preserved segments of the prehistoric city, including imposing two-story and three-story homes and world-renowned frescoes that attest to an advanced civilization with a high standard of living. Its residents had a sophisticated grasp of technology that allowed them to build ships and to evolve as a significant maritime trade force in the Aegean. Is this evidence enough to support the theory linking Atlantis to Santorini? Before going into that, let us look at what else Plato wrote about the lost continent.

“The location of the sunken continent has even come to constitute the object of research for serious scientists, some of whom have launched major search operations across the globe.”

Illustrations suggesting that Santorini was in fact Atlantis, from the seminal book Atlantis: The Truth Behind the Legend by eminent seismologist Angelos G. Galanopoulos (1910-2001) and British archaeologist Edward Bacon (1906-1981).

Having sired five sets of twins, Poseidon parceled out Atlantis in 10 parts. He gave the best part to his first-born son, Atlantis, after whom the continent and the ocean were named, and appointed him king over his brother kings. Their joint dynasty survived for several generations and acquired more wealth than any other before or afte0r it.

The island was much richer than necessary for its residents to live well. It had fertile lands (that yielded two harvests a year), lakes, rivers and natural thermal springs that were of particular benefit to the residents, as well as rich vegetation that fed a host of wild beasts, including large, voracious elephants. Its mines yielded ores in such quantities that the walls of the acropolis were dressed in orichalcum (or copper) that shone like fire, while the wall around the Temple of Poseidon and Cleito was made of gold.

This abundance of raw materials led to the construction of palaces that were and are considered unrivalled in elegance and splendor. The people built bridges over the circular seas and a canal connecting the outer to the inner ring, that was so big it could accommodate even the biggest ships. They also built underground dockyards and had two more ports that bustled with ships and merchants coming from every corner of the world.

What went wrong? For many generations, the people of Atlantis revered their divine heritage and remained pure of heart and mind, dedicating their lives to good works. The spirit of the divine, however, began to wane, as the human element prevailed and the people became intoxicated with wealth and passion, avarice and arrogance. Fuelled by a sense of their own omnipotence, they set out to conquer the entirety of Europe and Asia. In the war that ensued, they were defeated by prehistoric Athens, which saved the world from the threat of Atlantis. The coup de grace came from Zeus himself, who could no longer watch his chosen people continue on the road to perdition. Atlantis was surrendered to the ocean and swallowed whole.

Let us return to the scenario that places Atlantis in Santorini. According to Plato, Atlantis was bigger than Libya and Asia Minor combined. It was located at the Pillars of Heracles (present-day Gibraltar) and was destroyed in the 10th century BC.

These “facts” contradict our winsome Atlantologists, who, in order to give credence to their claim, have gone so far as to correct Plato. They argue, for example, that Plato was mistaken when he used the word “bigger” and meant, instead, “between.” By placing Atlantis “between” Libya and Asia Minor, however, they fail to explain how such a large expanse could fit in the Mediterranean basin.

Some Atlantologists also believe that the Pillars of Heracles represent two capes, one in Crete and the other in the Peloponnese, so far apart that travelers could not discern them when moving between the two. Can we really believe that Plato was so ignorant of geography that he confused these capes with the rocks of Gibraltar, which form the narrow straits between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean?

A third discrepancy concerns the date of the sinking of Atlantis. Plato attributes his information on Atlantis to three Egyptian priests who imparted it to Solon, one of the seven wise men of antiquity. Atlantologists argue that the priests were mistaken in believing that the continent disappeared 9,000 years before Solon’s time, indeed placing the date 1,100 years before. This is, indeed, convenient as it puts the date at around 1500 BC and associates the destruction with Minoan Crete and the Santorini volcano.

In the Platonic narrative, Atlantis was made up of concentric rings of land and sea. Atlantologists say that Santorini, together with the two small islets in its caldera, Thirasia and Aspronisi, are what remains of the central circle, while Crete formed part of the outer ring. This means that they designate Santorini the capital of Atlantis and, by extension, of Minoan civilization, something that cannot be the case, as Santorini was part of the Cycladic civilization.

What can we infer from all this? It is true that Atlantis has all the attributes to feed the imagination. It was the victim of divine destruction, like Sodom and Gomorrah, because its arrogant and bellicose residents provoked the wrath of the gods. That an entire continent was swallowed by the sea also reminds us of the scale of change that major natural disasters can bring to the world map, as was the case with Santorini. Mainly, though, the legend of Atlantis speaks to every human’s dream of an ideal state. Like the rest of us, the Atlantologists wish that such a state had really existed; the difference is that they want it to have done so at any cost.

“That an entire continent was swallowed by the sea also reminds us of the scale of change that major natural disasters can bring to the world map, as was the case with Santorini.”

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...

Discover hidden beaches, authentic tavernas, ancient...

From temples and festivals to front...

From Samos to Crete, we've selected...