Ancient Greek art is renowned for its significant contributions to the world of aesthetics and artistic expression. While it is challenging to narrow down the influence to just five artifacts, here are five important objects that had a profound impact on the early development of Greek art, from the mid-8th century BC to the mid-5th century BC.

The Hirschfeld Krater (c. mid-8th century BC)

Discovered in the Dipylon cemetery in Athens, in the Kerameikos – literally, “the city of clay” (the old potters quarter) – the Hirschfeld krater, derived from a type of mixing bowl, dates back to the Late Geometric period, ca. 750 BC. The ancient Greeks used many types of kraters, mainly to mix wine and water and as libation receptacles, but this particular example was used as a grave marker, likely commissioned for the burial of wealthy, high-status individual.

Thanks to its enormous size, standing over one meter in height, and its distinctive artistic features, the Hirschfeld krater is widely regarded as the high point of Geometric art (900-700 BC), a time when Greek culture was undergoing a major revival following the collapse of Bronze Age civilization, c. 1200 BC. Nearly 50 examples of similar vases have been found in the Kerameikos, attributed to the workshop of the so-called “Dipylon Master,” known to have been active in Athens in the mid-8th century BC. All of them follow more-or-less the same design, including intricate geometric patterns, such as meanders, zigzags, concentric circles, and triangles, but their main innovation is the use of narrative elements that depict elaborate funerary and mourning rituals, providing key insight into the funerary customs of the time. These scenes, which feature highly stylized human and animal figures, include the “prothesis” (the washing and laying out of the dead), the “ekphora” (funeral procession), horse-drawn chariots, and rows of mourners tearing their hair.

In terms of technical advancements, the Dipylon kraters were made using the pottery wheel, which was first introduced at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, and allowed for more precise shaping and larger vessels sizes. But their standout achievement was their inclusion of intricate narrative elements, representing an early example of storytelling through visual art, a feature that would dominate ancient Greek art in later periods.

© Public domain

© Public domain

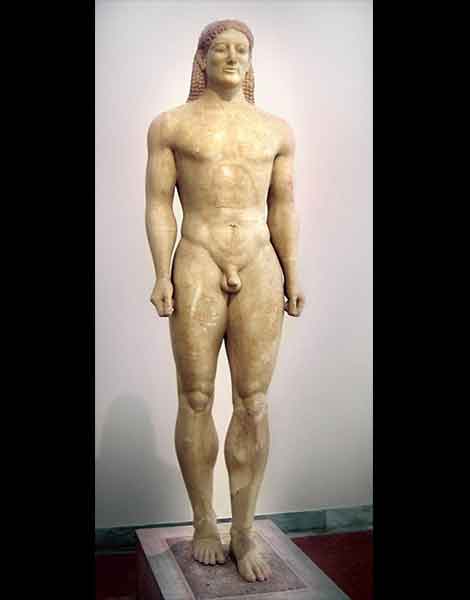

The Kouros of Kroisos (c. 530 BC)

During the Archaic period (700-480 BC), the creation of increasingly life-like human statues became a prominent feature of ancient Greek art. The famous “kouroi” (singular: kouros) and korai (singular: kore) sculptures, depicting male and female figures respectively, exhibited a key transition from the more rigid, Egyptian-inspired style to a more naturalistic representation of the human form.

One of the most iconic kouroi from this period is the “Kouros of Kroisos,” illegally unearthed from a burial mound in the countryside around the coastal town of Anavyssos, southeast Attica. The free-standing marble statue depicts a nude male youth, nearly two meters tall (6.4 feet), with broad shoulders and a strong, athletic physique. In characteristic pose, he stands with one foot forward (his left), arms fully extended along the sides of the body, and his face depicts the enigmatic “archaic smile.” On the base is inscribed the verse: “Stop and grieve at the tomb of the dead Kroisos, slain by the wild Ares in the front rank of battle.”

The Kouros of Kroisos exemplifies the artistic advancements of the Archaic period, as sculptors strived to achieve more life-like anatomical details, with an emphasis on body proportions and musculature. This was accomplished through the use of fine toothed chisels and abrasives, enabling the craftsman to achieve a smooth finish on the marble. Like many other kouroi, it served as a burial monument, honoring Kroisos, who fell in battle; representing the deceased in idealized form and in the flower of youth.

The influence of the Kouros of Kroisos can be seen in the works of renowned sculptors such as Polykleitos, one of the most important sculptors of the 5th century BC, who was able to achieve more life-like poses.

© Public domain

The frieze of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi (c. 525 BC)

The Siphnian Treasury was a small building located in the sacred sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, erected by the islanders of Siphnos around 525 BC. The treasury housed lavish votive offerings to Apollo, reflecting their wealth and power, and was described by the 5th century BC historian Herodotus as among the richest at Delphi.

The building is best known for its ornate marble frieze, a relief decoration that encircled the building above the epistyle (chief beam). Depicting scenes from Greek mythology, including the Assembly of the Gods at Troy on the east face, and the Battle of the Giants (“Gigantomacy”) on the north, the shallow bas-relief is the earliest known example of a continuous narrative in Greek sculpture – a forerunner of the famous Parthenon frieze, completed nearly a hundred years later.

While only fragments of the Siphnian Treasury frieze have survived, their artistic style are characteristically Archaic, showing individual figures in fontal or semi-frontal positions, rendered in rigid, formulaic poses. Nevertheless, the scenes capture moments of intense action and movement, demonstrating a clear ability to convey expressive figures and increasingly complex compositions. The frieze also showcases intricate details not seen before in relief sculpture, including delicate folds in clothing and, like the Kouros of Kroisos, greater anatomical accuracy of the human form.

The frieze had a lasting impact on ancient Greek art, influencing not only the development of relief sculpture by demonstrating new possibilities in composition, but the whole concept of narrative storytelling. Its integration of mythological and historical subject matter became a common theme in subsequent Greek art.

© Public domain

© Public domain

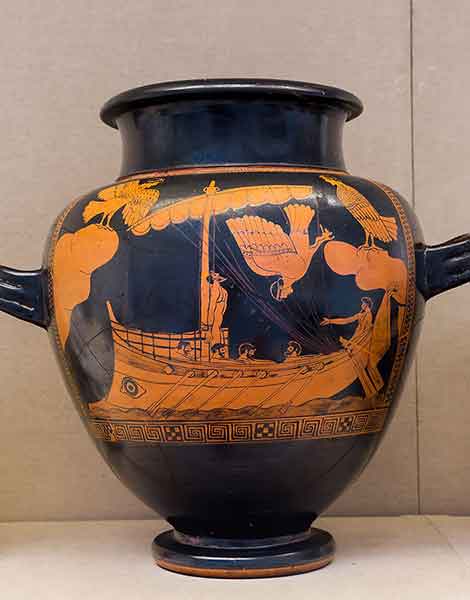

The Siren Vase (c. 480-470 BC)

A large painted stamnos, a type of vase that was typically used to store liquids, the “Siren Vase” stands nearly 80cm tall and is decorated with an elaborate mythological scene in the red-figure technique.

The main panel portrays the Homeric hero Odysseus and his encounter with the Sirens, mythical creatures who lured sailors to their deaths with their enchanting songs. In the scene, Odysseus is tied to the mast of his ship, while his companions, having plugged their ears with beeswax, continue to row. The Sirens, depicted as birds with female heads, swoop around them.

The artistic style and narrative representation of the Siren Vase are significant for several reasons. Firstly, the red-figure technique, where the figures are depicted in red on a black background, allowed for greater detail, depth, and expressiveness. Developed in Athens in the late 6th century BC, it replaced the previously dominant black-figure style by the first decades of the 5th century BC, and remained in use until the late 3rd century BC. Attributed to the so-called “Siren painter,” the vase is one of the most outstanding examples of this technique, showcasing the use of fine lines and intricate brushwork.

Secondly, the depiction of the Sirens reflects the importance of mythology in ancient Greek culture and its integration into the visual arts. The Sirens were popular mythical figures associated with the dangers of temptation and the allure of forbidden desires. The inclusion of such mythological themes on the Siren Vase helped to reinforce cultural narratives and moral messages for the viewers. Indeed, stamnoi vases were often used at “symposia,” notorious all-male drinking parties that celebrated special occasions. The inclusion of these mythical creatures on the vase may have reminded the participants of the symposium not to go overboard!

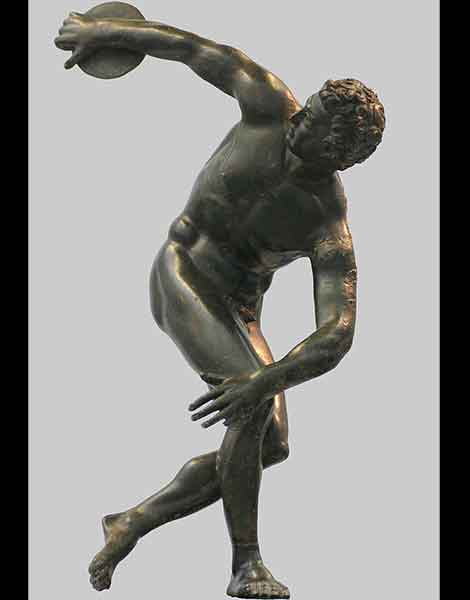

The Diskobolos (c.460-450 BC)

The Diskobolos (“discus thrower”) is widely regarded as one of the most iconic examples of ancient Greek art. The original bronze sculpture, attributed to the Athenian sculptor Myron and dated to the mid-5th century BC, is lost, but the work is known through numerous full-scale copies from the Roman period, in both bronze and marble. Depicting a young male athlete in the act of throwing a discuss, the Diskobolos is celebrated for its representation of athletic beauty and dynamic movement.

The statue represents a major leap forward in terms of its portrayal of human anatomy, movement and expression; a departure from the rigid and stylized conventions of the earlier Archaic period. The figure is captured at the moment of preparation, with his body twisted and his weight shifted onto one leg. The athlete’s muscles are taut and his body displays a sense of balance and controlled energy, conveying a harmonious combination of grace, strength, and athleticism. This depiction of kinetic energy and athletic prowess was groundbreaking for ancient Greek art.

Renowned for its naturalist portrayal of the human form, the Diskobolos had a significant impact on subsequent generations of artists and sculptors, influencing the representation of movement, anatomy, and idealized beauty. It became widely admired and replicated in various forms, including copies, adaptations, and variations. These replicas spread throughout the ancient Greek world and even beyond, as the statue’s fame extended to Roman and later Renaissance art.

The statue also represents the importance placed on physical education, athletics, and the pursuit of excellence in ancient Greek society. It captures the spirit of competition, the idealized human form, and the celebration of the human body that were central themes in Greek culture during the Classical period.