The Secrets of Amalias Avenue

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

"The death of Markos Botsaris" by Marsigli Filippo (1790-1863)

© Google Art Project.jpg

Every Greek schoolchild knows the names of the heroes of the Revolution – larger-than-life characters like Kolokotronis, Papaflessas, and Bouboulina – whose exploits have been indelibly written into the Greek national consciousness.

But what about the experiences of the nameless and unfeted people of Greece during the decade-long struggle for independence? What do the history books say about their hopes and aspirations of the Elleniki epanastasi (“Greek revolution”)? And what did they think they were fighting for?

In his forthcoming book, “The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe”, Mark Mazower, the Ira D. Wallach Professor of History at Columbia University, tackles these hitherto overlooked questions by exploring how rural communities in the many diverse regions of Greece learned the common “language of revolution” and embraced the ideals of nationalism and self-determination, inspiring them to rise up against Ottoman rule.

There is no doubt that the Greek Revolution was a cardinal event, not only in Greek history, but also in the emergence of modern European nation-states over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The question of what happened in 1821 has been vigorously debated in countless books, articles, and other forms of media over the years, and remains a lively subject for discussion today. For many, it is an event that continues to define Greek religious, cultural, and ethnic identity.

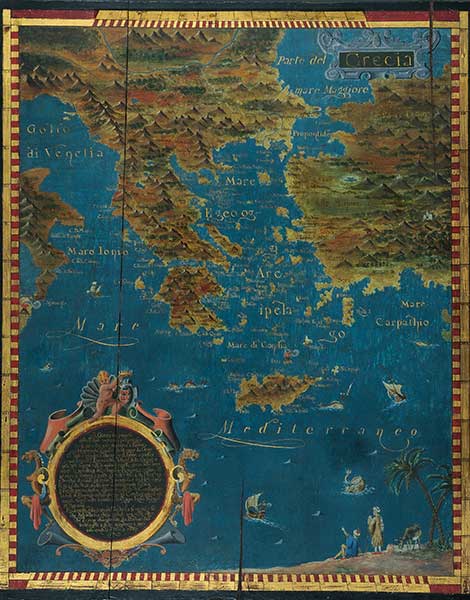

Map of Greece with notes in Italian. Late 17th–early 18th c., egg tempera on wood, 110x88.5 cm. Benaki Museum 33115, donated by Helen Keckeis-Tobler. The work will be among those included in the exhibition “1821, Before and After”, that will open at the Benaki Museum in March of 2021.

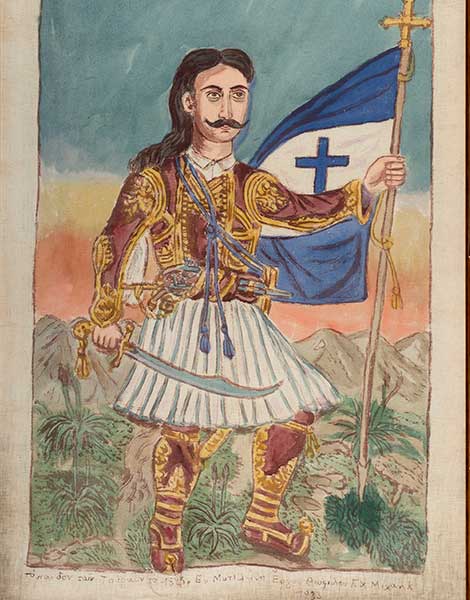

Theophilos Hadjimichael (1871–1934), The Hero Markos Botsaris, 1933, diluted oil on cloth, 119x81 cm. Alpha Bank Collection AA 4726. The work will be among those included in the exhibition “1821, Before and After”, that will open at the Benaki Museum in March of 2021.

Previous analyses have focussed on the roles of the individual leaders of the Greek revolution, the power and influence of the secretive Filiki Etaireia (“Society of Friends”), and the importance of the Philhellenes in stirring up public and political support abroad. Much has also been written about the role of European diplomacy and the intervention of the three great maritime powers, Great Britain, France, and Russia.

But the key element in its ultimately successful outcome was the endurance of the ordinary Greek people; the villagers whose day-to-day survival depended on the largely agrarian, subsistence economy, and who stood to lose everything if the uprising failed.

In a recent online talk commemorating the bicentenary of the Greek Revolution this month, Professor Mazower reflected on the events of 1821 and how the lofty aims of the epanastasi gained traction with the Greek peasantry. He discussed how emerging concepts of “nationhood” and Ellenikotita (“Greekness”) developed and spread among the rural communities, inspiring them to remain steadfast against overwhelming odds to eventually win the sympathy and support from abroad.

“In 1821, at the international level, there was no sympathy for the Greek cause. But the remarkable thing is that the Greeks held out long enough for that to change … It was the first time that the Great Powers were forced to recognise the power of nationalism,” Mazower argued.

The online event, co-hosted by the Consulate General of Greece in Boston and College Year in Athens, under the auspices of the Embassy of Greece in Washington, was live-streamed on Wednesday 3rd March 2021, and a video has since been uploaded to YouTube:

Mazower reflected on the term “Elleniki epanastasi” (“Greek revolution”), arguing that it was used at the time by metropolitan Greeks of a certain education in and around the Filiki Etaireia, but would have meant very little to the common Greek of the early 1820s. It was part of the European political discourse that had no purchase with them.

To help stir up enthusiasm and support for the revolution at the ground level, the circulation of the earliest handwritten and printed newspapers among the rural population played a key role in disseminating news of the insurgency.

In the first instance, these refrained from using the word “revolution”, instead declaring that the “Kings of Francia” (i.e. western Europe) had decided to “remake the Romeiko” – to restore Greece to its rightful condition, inspired by the glories of its classical past, and resurrect the Greek Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantine Empire.

“All through the mountains and islands, Greek communities were immersed in the language of popular millenarian Orthodoxy, in which the long-awaited triumph of Christ, thanks to the Virgin, was about to become true, and the Turkish sultan was to be chased out of Istanbul.”

While many Greeks continued to think of patrida (“home country”) in terms of their immediate locality or region, Mazower argues the principals of “Greekness” and “Orthodox Christianity” were used to mobilise the population in a way that had not been possible in the preceding 400 years of Ottoman rule.

“Nevertheless, the Greek Revolution went on far longer than anyone expected – longer than the Ottoman sultan expected, longer than the European diplomats expected, and, certainly longer than many of the leaders and heroes of the revolution expected.”

Greek society has known great suffering and trauma in its history, and Mazower identifies this as the real clue to understanding the significance of 1821: that the common people endured.

Konstantinos Volanakis (1837–1907), The Landing of Karaiskakis at Faliro, 1895, oil on canvas, 150x273 cm. Bank of Greece collection no. 527. The work will be among those included in the exhibition “1821, Before and After”, that will open at the Benaki Museum in March of 2021.

The seeds of Mazower’s forthcoming book were planted during the Great Recession of 2008, when severe austerity hit the global economy and it seemed as though Greece was losing its sense of sovereignty under the new regime of the troika.

The experience, too, of living through successive lockdowns during the current Covid-19 pandemic sharpened his focus, looking at how societies cope with prolonged episodes of suffering and trauma. These formative events, and how they impacted on Greek and other societies around the world, set him on the path of wanting to go back to the events of 1821 when people were fighting for their sovereignty.

At the beginning of the revolution, Mazower argues that many Greeks fought for Orthodox Christianity, but, as time wore on, much broader concepts of independence, nationhood, and sovereignty gained traction. As separate uprisings gathered momentum in different parts of the country, in the Peloponnese, Central Greece, and Crete, Ellenikotita developed as a major unifying theme over the course of the war, and nationalism and Orthodoxy became strongly intertwined.

The nations of the Balkans and eastern Europe took very different pathways to nationhood following the retreat of the Ottoman Empire. The events of 1821 and the endurance of the Greek people inspired other societies in Europe to seek their own sovereignty.

As Mazower argues, the Greek struggle for independence was “the first triumph of nationalism in Europe and the first creation of an independent nation state in the world.”

Ludovico Lipparini (1802–1856), The Oath of Lord Byron in Missolonghi, circa 1850, oil on wood, 16x19 cm. Benaki Museum 9009. The work will be among those included in the exhibition “1821, Before and After”, that will open at the Benaki Museum in March of 2021.

Western nations have always had a love affair with the history, literature, and art of ancient Greece, and ancient Greek symbolism and mythology played a key role in galvanising support among the classically educated European elites, most famously Lord Byron, who, among others, took up arms to fight alongside the revolutionaries.

There was also a feeling of sympathy among the ordinary citizens of Europe and further afield – an extension of the values that were developed during the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries. Mazower argues that this was also the beginning of the “Age of Sympathy” – the age we are still in – sympathy for oppressed populations and vulnerable minorities, which further encouraged the support from abroad.

The Greek population remained resolute in the face of great suffering and, in a bid to put an end to the conflict, the Great Powers finally intervened, sending a naval task force into the Aegean in the spring of 1827.

The resulting Battle of Navarino in October of that year destroyed the combined Ottoman and Egyptian fleets and assured the ultimate success of the revolution, but the crowning achievement of the Greek people had been their steadfast endurance; an achievement that had a fundamental impact on both Greek and European identity.

Burning and beached hulks of Ottoman warships under the cliffs of Navarino by Auguste Mayer.

The Bicentenary of the start of the Greek Revolution in 1821 is an opportunity to reflect on where Greece came from as a nation, and where it is going in the future.

As we grapple with the experience of living through a pandemic, and overcoming the challenges of restricted movement and an uncertain future, the events of 1821 and the endurance of the ordinary people of Greece still resonate today, serving as an inspiration for us all.

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

A major restoration project is bringing...

From historic landmarks to edgy street...

The Kerameikos archaeological site provides a...