Disability in Ancient Greece: Myths, Facts, and Accessibility...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

The National Archaeological Museum, the largest museum in Greece, is a “must-see” destination for any visitor arriving in Athens.

© Perikles Merakos

Founded in 1866, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens (NAMA) stands as Greece’s premier institution dedicated to preserving and showcasing the country’s rich cultural heritage. Housed in an elegant neoclassical building, a short walk from Omonia Square, the Museum’s holdings span a vast chronological range, presenting a unique panorama of Greek civilization from earliest prehistory to late antiquity.

It would be remiss of any visitor to the Greek capital to pass on the opportunity of spending at least a couple of hours wandering the halls and galleries of this venerable museum. Besides its permanent collection of 11,000 exhibits, there is a revolving door of temporary exhibitions, showcasing priceless artifacts from other Greek and international institutions. There is always something on display to suit all tastes and ages, and levels of interest.

Nevertheless, a visit to such a big museum can be daunting. With so many things to see, it’s tricky to know where to start. To whet your appetite, we’ve cobbled together a list of 16 must-see exhibits in the NAMA’s permanent collection, plus a cheeky (spoiler alert: non-Greek) bonus object at the end. As ever, this list is by no means exhaustive, but it will certainly get you started, and provide you with a general overview of the artistic development of Aegean/Greek culture through the ages.

If you are visiting with young children, you could use the following list as a “treasure hunt,” exploring the Museum’s galleries like mini Indiana Jones’, in search of each exhibit.

An engaging marble figurine known as the "Harpist" (Early Cycladic II period), from the island of Keros, southeast of Naxos.

© Public domain

On display in the prehistoric galleries, located on the Ground Floor, is a quirky little statuette, commonly referred to as the “Harpist” or “Lyre Player.” This idiosyncratic marble object hails from the island of Keros, and belongs to the so-called Keros-Syros Culture. Crafted during the Early Cycladic II period (c. 2800–2300 BC), it portrays a seated male figure playing a harp (or lyre?) with schematic simplicity. The figure is rendered in the distinctive Cycladic style, characterized by smooth, elongated, almost otherworldly-like features, highlighting the culture’s obsession with geometric abstraction. Wrap your head around this: it was carved from one single block of marble!

The mysterious "frying pan" from Syros, NAMA 4974.

Staying in the prehistoric galleries, amid artifacts from the mysterious Early Cycladic culture, see if you can find this enigmatic object: the so-called “frying-pan” NAMA 4974 from Chalandriani on Syros. This strange-looking artifact, made of coarse-grained clay and crafted around 2800–2300 BC, is best described as a flat circular disk, 20.1 cm across, with two grips acting as footed handles. The pan’s significance lies in its intricate incised decoration, depicting a highly stylized representation of an oared ship with an upward pointing prow, surmounted by a fish symbol and two banners, set in a field of swirling spirals (waves?). This finely detailed scene doubtless reflects the maritime culture and economic importance of the sea for the Early Cycladic culture, but archaeologists are puzzled as to the original purpose of the object. Any ideas?

For more on the Cycladic frying pan, click here.

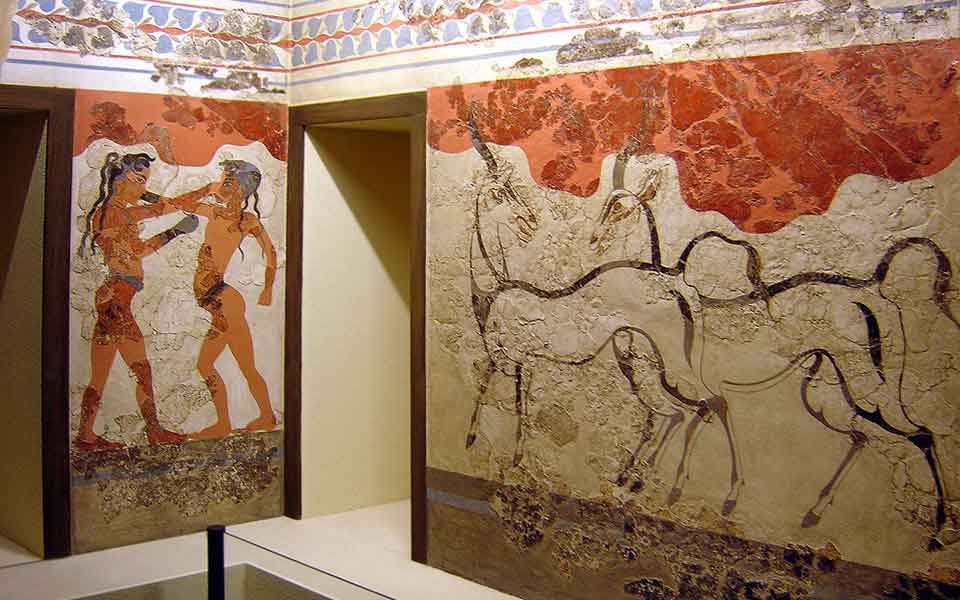

The Akrotiri Boxer Fresco, seen on the left.

© Public domain

Still on the Ground Floor, amid the Collection of Antiquities of Thera, is a vivid, brightly colored mural depicting two young boys engaged in a boxing match. The so-called “Boxer Fresco” hails from the famous Cycladic Bronze Age settlement of Akrotiri on Thera (Santorini), and is dated to the Late Minoan period (c. 1600 BC). Its excellent state of preservation is thanks the volcanic eruption in the 16th century BC, which buried Akrotiri in thick layers of ash. In the fresco, the young athletes both wear loin cloths and their heads are shaved but for two long locks at the back and two shorter ones above the forehead. Intriguingly, the boy on the left wears a necklace and two bracelets, one on his arm, the other around his ankle. Scholars believe this may indicate higher status. The scene provides key insight into the significance of sports in Bronze Age Minoan/Cycladic culture, portraying the physical prowess and competitive spirit embedded in their society.

Gold death mask, famously known as the “Mask of Agamemnon,” found in Grave Circle A at Mycenae. Discovered in 1876 by amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, the mask is on display in Room 4 of the National Archaeological Museum.

© Shutterstock

The hauntingly beautiful “Mask of Agamemnon” is perhaps one of the most iconic artifacts on display at the NAMA. Made entirely of gold, it was discovered by pioneering archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in Grave Circle A at the Late Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae, in 1876. Associated with the legendary king Agamemnon, commander of the Achaean forces at Troy, later researchers have nevertheless dated the mask to the second half of the 16th century BC, predating the period of the Trojan War by some 400 years. Whatever its origin, the funeral mask would have covered the face of a deceased member of the Mycenaean ruling elite, and is one of the best-known examples of art from the Late Bronze Age (1600-1100 BC). Its demure facial features, described as the “Mona Lisa of prehistory,” intricate repoussé work, and symbolic link to Greek mythology contribute to its allure.

For more on the Mask of Agamemnon, click here.

Boar’s tusk helmet with cheek-guards and a double bone hook on top. Mycenae, chamber Tomb 515.

© Public domain

The Dipylon Vase

© Public domain

Also in the Collection of Mycenaean Antiquities is a remarkable piece of Late Bronze Age military equipment, a Boar’s Tusk Helmet. If you’ve read Homer’s “Iliad,” you may remember the description of just such a helmet in Book Ten, as Odysseus prepares to go on a nighttime raid against the Trojans. Discovered in Tomb 515 at Mycenae, and dated to the 14th–13th centuries BC, this helmet is made up of dozens of individually shaped boar tusks, arranged in a radiating pattern around a bronze frame. It’s distinctive for a double bone hook on top (to affix a crest?) and long cheek-guards, offering extra protection to the sides of the face. Reflecting the ingenuity of Mycenaean craftsmanship, it combines both decorative and functional elements, and illustrates the martial prowess of Mycenaean Greek society. Aside from hunting huge numbers of wild boars and extracting the necessary number of tusks, this helmet would have taken hundreds of working hours to make and would have certainly been worn by a member of the elite warrior class.

Moving on to the collection of exhibits from the Geometric Period (1050-700 BC), displayed on the 1st Floor, the “Dipylon Vase,” also known as “Athens 804,” is a richly detailed funerary vessel dated to the mid-8th century BC. Discovered in the Kerameikos cemetery (ancient potters’ quarter) of Athens, and standing over one and a half meters tall, this Late Geometric-style vase features intricate scenes of a “prothesis” (funeral preparation) and a somber funeral procession, made up of schematic human figures (mourners) with triangular torsos and narrow waists, animal motifs, and an array of ornamental geometric patterns. Its impressive size and detailed narrative showcase the cultural significance of funerary rituals in early Greek society, providing a glimpse into the beliefs and practices surrounding death in the shadowy Geometric period. The impressive-looking vessel also highlights the early evolution of Greek ceramic art and storytelling techniques.

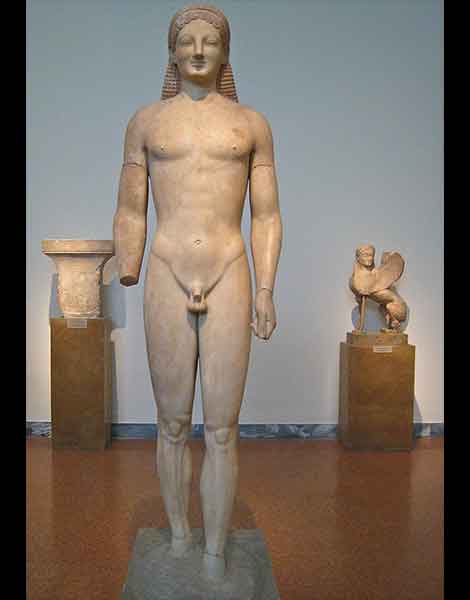

The Merenda Kouros

© Public domain

Grave Stele of Aristion

© Public domain

The Ground Floor of the Museum boasts an impressive sculpture collection, featuring some of the best examples of Archaic Greek (c. 800-480 BC) statuary in the world. Of note are the distinctive marble statues of youthful males and females, known as kouroi and korai. These enigmatic statues, featuring the famous “Archaic smile,” showcase the evolving aesthetic principles of balance and anatomical precision in ancient Greek art. The best examples in the collection are a pair of statues made of smooth Parian marble, one naked youth (kouros) and one maiden (kore), from Merenda in Attica, dated to the mid-6th century BC. Both are slightly larger than life-size (1.89m and 1.79m respectively) and represent the transition from the rigid Archaic to the more naturalistic Classical style. The naked kouros projects a sense of youthful athleticism, while the kore embodies grace and elegance.

The Stele of Aristion, exhibited amid other sculptures from the Archaic period, is a poignant grave marker, dated to around 510 BC. Carved in Pentelic marble, this funerary stele commemorates Aristion, a young Athenian hoplite (armored infantryman), who may have died in battle. Standing more than two meters high, its gentle relief depicts the deceased in a dignified stance, wearing a cuirass (breastplate), helmet and greaves (shin guards), and holding a long spear in his left hand, as if standing guard. At the top of the base is an inscription, giving the name of the deceased in the genitive: Ἀριστίονος “Aristion’s.” This stele stands as a testament to ancient Greek notions of honor and valor in death, providing a tangible link to the cultural and military history of Athens during a pivotal period in the early development of democracy.

A Classical bronze statue of Poseidon/Zeus (c. 460 BC) recovered in 1926-1928 from a shipwreck off the north Evian coast.

Another iconic exhibit in the NAMA’s statue collection, featured on the front of countless books and posters, is the famous “Artemision Bronze,” discovered in the sea near Cape Artemision, northern Evia. This well-preserved masterpiece of early Classical sculpture, dated to around 460 BC, showcases sublime craftsmanship. Standing at 2.09m, the dynamic, athletic figure is believed to represent either the sea god Poseidon or the thunder god Zeus. Opinions differ as to whether the right hand was originally wielding a trident or a thunderbolt. The statue’s “contrapposto” stance with outstretched left arm, powerful musculature, and meticulous detail emphasize the divine strength and aesthetic ideals of Classical Greek art.

Upstairs, amid artifacts unearthed during the 1891 excavations in the ancient cemetery of Kerameikos, lie two well preserved skeletons. Both were found in sarcophagi buried in a thick layer of mud, and surrounded by an assortment of grave goods. Dated to 460 BC, these inhumations provide important clues about burial customs in Classical Athens. Not for the squeamish or faint hearted, the forensic study of human remains offer unparalleled insight into the daily lives of ancient people, including their nutrition, and any information about disease or other pathological conditions or traumatic injuries.

Marble Grave stele of Mnesagora and Nikochares, c. 420-410 BC.

© Lefteris Papaulakis - Shutterstock

A close up of Nikochares

© Lefteris Papaulakis - Shutterstock

Another poignant grave marker – a reminder that people in the ancient past shared deep emotions like us – is the marble Stele of Mnesagora and Nikochares, discovered in the vicinity of Vari, Attica. It was widely regarded one of the finest examples of Classical Greek Greek funerary art. Crafted sometime around 420-410 BC, the 1.19m-tall stele commemorates a young girl, Mnesagora, and her infant brother, Nikochares, who perished together. The relief depicts the deceased pair in a touching scene, showcasing intricate details and facial expressions. Mnesagora is seen standing, her wavy hair in a bun, and wearing a sleeved chiton (long tunic) and himation (heavier wrap). In her left hand she holds a bird by its wings. Nikochares is depicted nude and on one knee, reaching out to grasp the bird. This intimate portrayal reflects the High Classical ideals of love and familial bonds, and stands as a timeless symbol of remembrance and human connection.

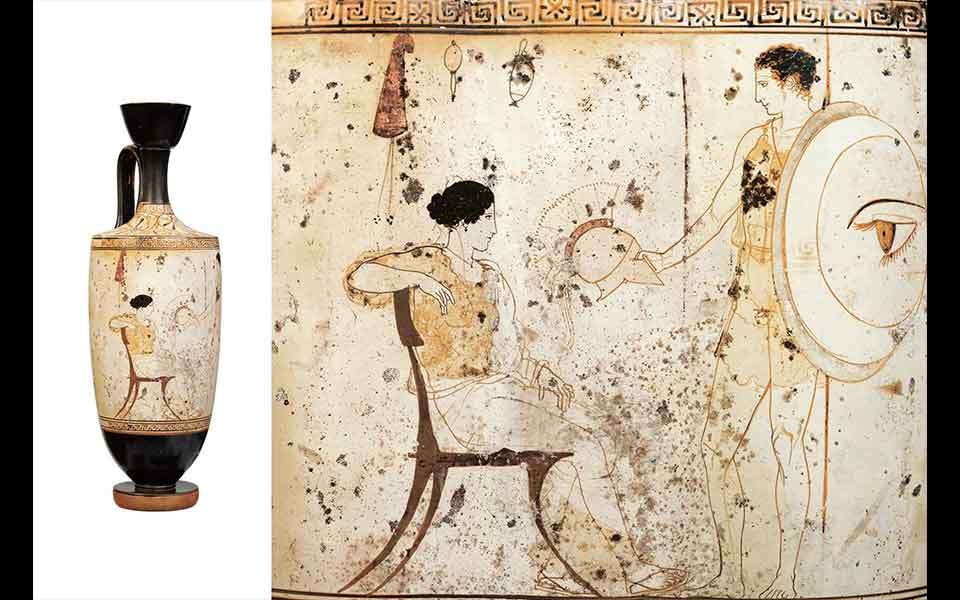

The "Farewell Scene." Painted on a White Ground Lekythos by the Achilles Painter, c. mid-5th century BC.

© Public domain

Found amid the vases and minor arts, this dainty little lekythos, used for storing oil, depicting another touching scene, that of a departing warrior. Dated to the mid-5th century BC, this Attic White Ground vessel, so called because the figures appear on a white background, was likely made for ritual and funerary use. A young woman is seen sitting, bidding farewell to a young hoplite, his right arm outstretched and holding a crested Corinthian helmet. The “Farewell Scene,” which scholars have attributed to the Achilles Painter, is rendered with exceptional grace and delicacy on the white background. The attention to detail in the figures’ gestures and expressions imparts a timeless quality, immortalizing the sorrow and human emotions associated with parting and loss.

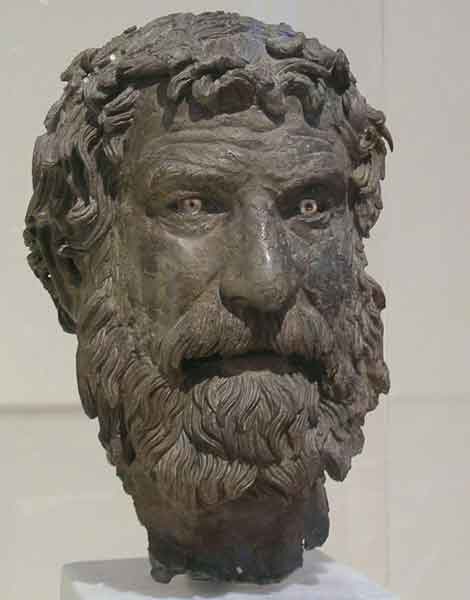

Bronze head of a philosopher from the Antikythera shipwreck, possibly of Bion of Borysthenes (c. 325-250 BC).

© Public domain

Scattered fragments of the famous Antikythera Mechanism were also found on the seafloor.

© Public domain

This chillingly lifelike bronze head of a philosopher, recovered from the Antikythera shipwreck south of the Peloponnese, is notable for his piercing stare, thanks to the inlaid white irises in his eyes. Dated to around 240 BC, the head was found on the seabed alongside the scattered arms, legs and clothed torso of the same statue. Despite his dishevelled demeanour, with unkempt hair and shaggy beard, the philosopher’s serene expression and extraordinary attention to detail (note the frown lines across his forehead) showcase the Hellenistic mastery of bronze portraiture. Scholars have argued that the head likely represents a Cynic philosopher, probably Bion of Borysthenes (c. 325-250 BC), who was famous for his scathing attacks on organized religion.

The “Jockey of Artemision” (c. 140 BC)

© Perikles Merakos

The Horse and Jockey bronze, also known as the “Jockey of Artemision,” is a masterpiece of ancient Greek art. Recovered in pieces from the seafloor off Cape Artemision, north Evia, and dated to around 140 BC, this exquisite sculpture captures the dynamic energy of horse racing. The young jockey, a boy, appears to be holding reins in his left hand a riding crop (whip) in his right, urging the galloping horse forward. With an overall length of 2.9m and 2.1m in height, the sculpture is approximately life-size, and boasts extraordinary anatomical precision and lifelike detail, The dynamic composition and fine craftsmanship showcase the Hellenistic era’s mastery of bronze sculpture.

The Antikythera mechanism is one of the prize objects at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

© Shutterstock

One of the most famous artifacts from the ancient world – not to mention featuring as the main plot device in the recent Indiana Jones film – the Museum is home to the iconic Antikythera Mechanism, a marvel of ancient engineering and astronomical knowledge. Recovered from a shipwreck near Antikythera, this complex mechanical device from around 100 BC was likely used a celestial calculator and calendar. Comprising intricate gears and dials, it tracked planetary movements and predicted celestial events, showcasing an advanced understanding of astronomy. This artifact challenges preconceptions about ancient technological capabilities, highlighting a sophisticated level of scientific inquiry, and merging artistry and scientific innovation in a single extraordinary device.

For more on the Antikythera Mechanism, click here.

This group statue of Aphrodite, Pan and Eros (c. 100 BC) exhibits all the whimsical humor, elegance, sexual playfulness and mythological fascination that we so often associate with the ancient Greek world.

Made of Parian marble, this remarkable statue, depicting the goddess of love Aphrodite, the rustic, goat-legged Pan, and a mischievous winged Eros, was found in the “House of the Poseidoniastai of Beryttos” (Beirut), on the sacred island of Delos. Standing at 1.55m and dated to around 100 BC, the composition is a testament to the artistic brilliance of Hellenistic sculptors, capturing the divine grace of Aphrodite, the wild energy of Pan, and the playful charm of Eros. The intertwining figures showcase a dynamic balance between sensuality and rusticity, with the nude Aphrodite fending off Pan’s sexual advances with her sandal, as Eros comes to her aid. Originally, the statue would have been brightly painted.

Visitors to the Museum are often surprised to discover a small but rich collection of Egyptian antiquities, on the Ground Floor. The core of the collection was donated by two Greek expatriates from Egypt, Ioannis Dimitriou and Alexandros Rostovich, in 1880 and 1904 respectively, and further enriched by donations from the Greek Archaeological Society and the government of Egypt, among others.

Among the many gems in this collection is a small wooden funerary model of a ship with its crew, dated to the 12th Dynasty, 1994-1782 BC. Boat models were common grave goods in ancient Egypt, symbolizing the sacred journey of Osiris in the afterlife. In a museum full of bronze and marble statues, and ceramic vessels, it’s astonishing to see such an old, delicately made, yet beautifully preserved wooden object on display.

NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM OF ATHENS 44 Patission • Tel. (+30) 213.214.4800

Opening hours:

November 1st – March 31st Tuesday: 13:00-20:00 From Wednesday until Monday: 08:30-15:30

April 1st – October 31st Tuesday: 13:00-20:00 From Wednesday to Monday: 08:00-20:00 The National Archaeological Museum is closed on 25-26 December, 1 January, 25 March, Orthodox Easter Sunday and May 1st. *Οn Good Friday and Holy Saturday, the Museum’s opening hours are as follows: Good Friday: 12:00-17:00 Holy Saturday: 08:30-15:30 On Easter Sunday the Museum is closed. Admission: 12€ (From April 1st until October 31st) 6€ (From November 1st until March 31st) Three day Special ticket package: 15€ Valid for National Archaeological Museum, Epigraphic Museum, Numismatic Museum and Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens. For more information on the Permanent Collections and temporary exhibitions, check out the Museum website.

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

Archaeologists at the site of Aghios...

Discover five of Athens’ latest openings,...

Souvlaki joints started appearing in earnest...