The Greek myths are chock-full of creatures that excite and terrify the imagination. As Halloween draws near, we explore some of antiquity’s most spooktacular beasts!

In ancient Greek mythology, strange and terrifying creatures played a significant role as both antagonists and symbols of humanity’s deepest fears and desires. These fearsome beasts were often regarded as the embodiments of chaos, representing the consequences of human folly. In the same way, they served as cautionary tales, highlighting the importance of virtue, heroism, tenacity, and cleverness. Heroes like Heracles, Theseus, and Perseus faced some of these creatures as part of their quests. By overcoming them, they showcased their strength, bravery, and divine favor with the gods, contributing to their legendary status.

In some stories, scary monsters symbolized primordial forces or natural phenomena, such as the regenerative power of water or the destructive force of storms, while other times, they delved into the darkest depths of the human psyche, serving as allegorical representations of human struggles. Most importantly of all, they became cultural touchstones, appearing in ancient Greek literature and art, influencing later cultural traditions.

As we approach the festival of Halloween (October 31, “All Hallow’s Eve”), with its roots in Samhain, the ancient Celtic festival that marked the onset of winter, we thought it would be fun to put together a list of the most spine-chilling creatures from Greek mythology, to get you in the mood for the “darker half” of the year. In no particular order, we’ve picked out some of the more famous beasts from the most iconic tales, as well as a couple of shadowy creatures from lesser-known myths.

Which ones would you be terrified to encounter on a cold, moonless night? Read on … if you dare!

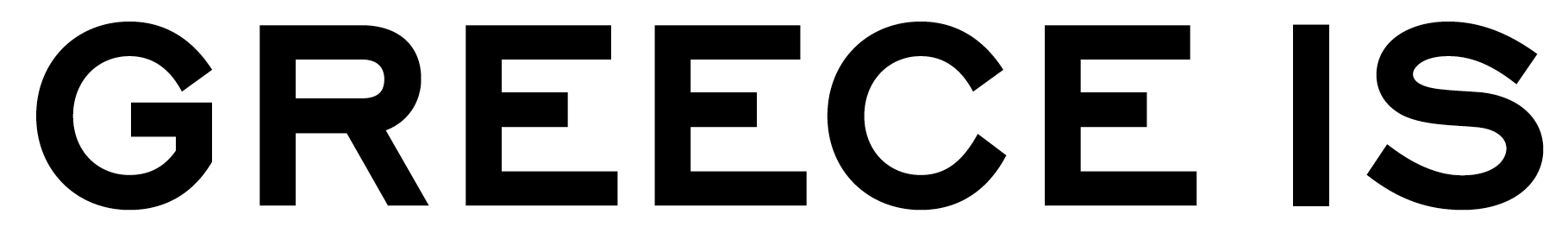

Guarding the gates of the Underworld. "Cerberus," by William Blake (1757-1827).

© Public domain

Cerberus, the Hound of Hades

One of the most ferocious creatures from Greek mythology is Cerberus, known to the ancients as the dreaded “hound of Hades.” This monstrous three-headed (sometimes “multi-headed”) dog was said to have guarded the entrance to the Underworld, the realm of the Dead, preventing the living from entering and the deceased from escaping. With a serpent’s tail and a mane of snakes, Cerberus is the embodiment of terror and the finality of death.

His role in the mythological narrative is primarily as a guardian, standing at the threshold of the afterlife, under the rule of Hades, god of the Underworld. As a symbol of the boundary between life and death, Cerberus emphasized the inexorable nature of mortality in ancient Greek religion.

In one of the most famous stories, the divine hero Heracles, as the last (and undoubtedly the riskiest) of his Twelve Labors, was tasked with subduing Cerberus without the use of weapons and bringing him to the surface. The battle-scarred hero journeyed to the Underworld and sought permission from Hades himself. By grappling with the fearsome creature with his bare hands, Heracles demonstrated his immense strength and bravery. He later presented the dog to Eurystheus, king of Tiryns, the man who assigned Heracles his labors.

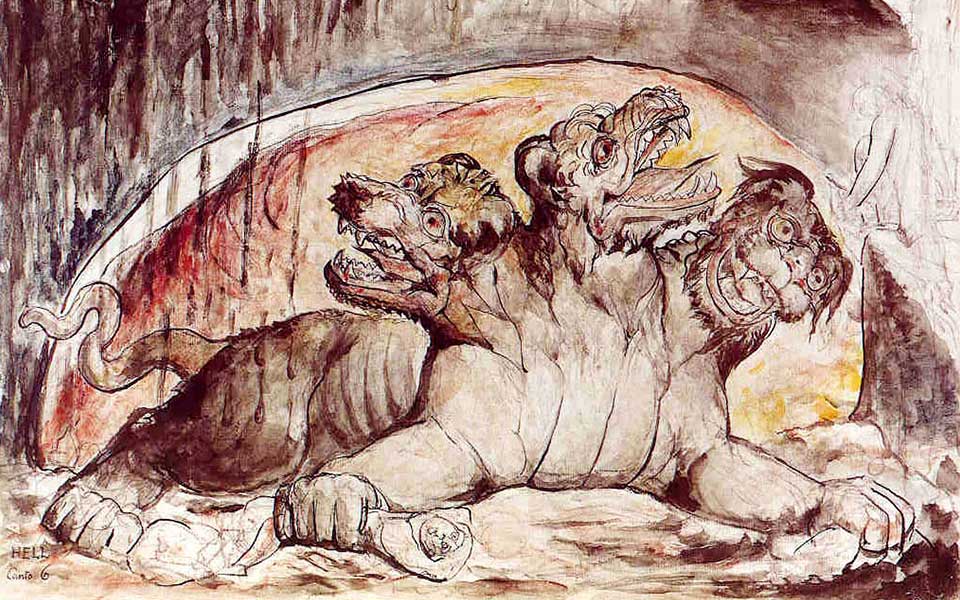

The blinded Polyphemus seeks vengeance on Odysseus, by Guido Reni (1575-1642). Painting in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

© Public domain

A 1st century AD head of a Cyclops, discovered in the Roman Colosseum.

© Public domain

The Cyclopes

The Cyclopes were a race of one-eyed giants with incredible strength and crafting skills. They were known for their distinctive feature, a single eye in the center of their foreheads. Among the most famous were the three sons of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth) – Brontes, Steropes, and Arges – as mentioned in the famous “Theogony” (Origin of the Gods), composed by the epic poet Hesiod (c. late 8th-early 7th century BC).

The Cyclopes played a significant role in several important myths. They were initially imprisoned in the depths of Tartarus (the ancient Greek equivalent of Hell) by Uranus but were later freed by their grandchild Zeus during the Titanomachy, the war between the Titans and the Olympian gods. In gratitude, they provided Zeus with his mighty thunderbolts.

The most well-known encounter with a Cyclops is described in Homer’s “Odyssey,” composed sometime in the 8th century BC. In their voyage home to Ithaca (Ithaki) from the Trojan War, Odysseus and his crew find themselves trapped in the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus, who begins to devour them, one by one. Through clever tactics, Odysseus and his men manage to blind the cyclops and escape, provoking the wrath of Poseidon, Polyphemus’ father. In his fury, the sea god prevents and frustrates Odysseus’ attempts to sail home for ten, long years.

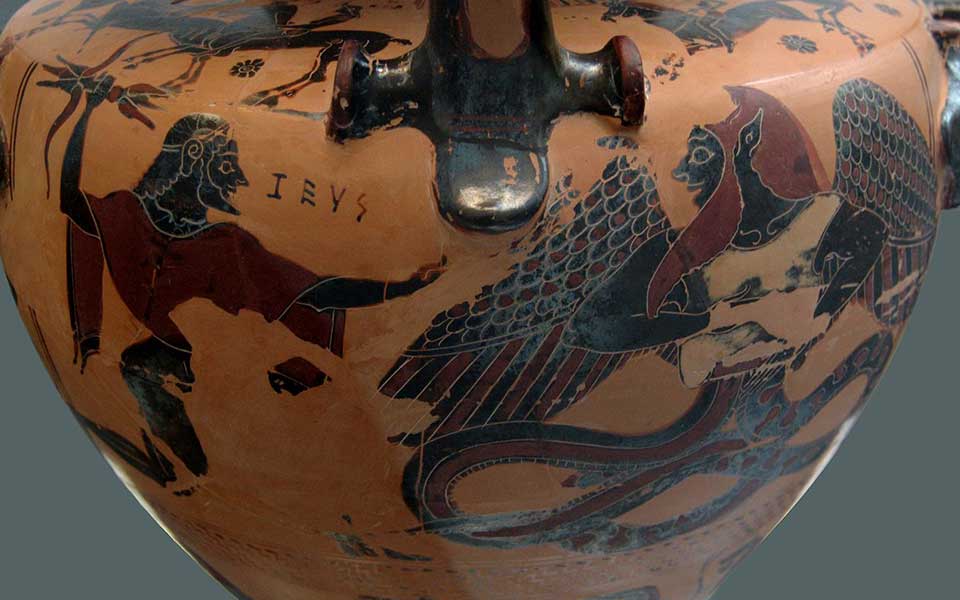

Zeus aiming his thunderbolt at a winged and snake-footed Typhon. Chalcidian black-figured hydria (c. 540–530 BC), Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich.

© Public domain

Typhon

One of the lesser-known creatures to make this list is the fearsome Typhon, regarded by the ancients as one of the deadliest and most formidable adversaries of the gods. The poet Hesiod described him as a giant, fire-breathing creature with a hundred snake heads, flashing eyes and flickering tongues, and a loud, thunderous voice. Typhon’s lower body was made up of coils of snakes, and his size was so immense that, according to the “Bibliotheca” of Pseudo-Apollodorus, a compendium of Greek myths and heroic legends composed in 1st or 2nd century AD, his head “reached the stars.”

Typhon is best known for his battle against Zeus, the king of the gods. In this epic conflict, Typhon challenged the Olympians and unleashed a reign of terror, threatening to overthrow their dominion of the Cosmos. Zeus ultimately defeated Typhon with his thunderbolts, trapping the monster beneath Mount Etna in Sicily, where his fiery breath causes volcanic eruptions.

Typhon’s mythology represents the uncontrollable forces of nature, specifically volcanic eruptions, and the eternal struggle between order and chaos in the Cosmos. His defeat by Zeus exemplifies the triumph of the divine order over primal forces.

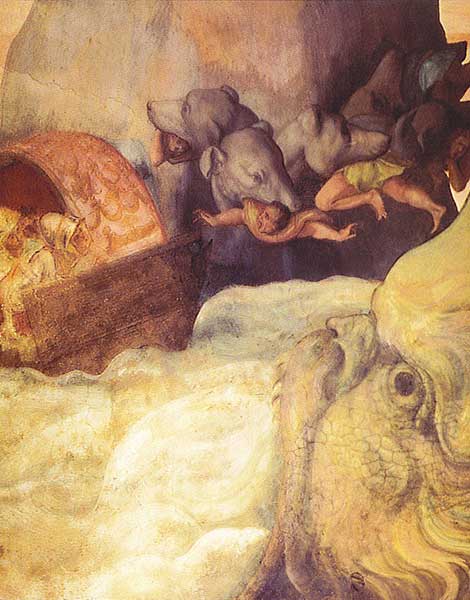

Henry Fuseli's painting of Odysseus facing the choice between Scylla and Charybdis, 1794–1796.

© Public domain

Top, each of Scylla's heads plucks a mariner from the deck; bottom right, Charybdis tries to swallow the whole vessel. Italian fresco.

© Public domain

Scylla and Charybdis

Scylla and Charybdis are legendary sea monsters associated with the treacherous Strait of Messina, the narrow passage between Italy and Sicily. Positioned on either side the strait, they represented a perilous maritime obstacle faced by sailors in antiquity.

Described as a multi-headed sea monster, Scylla was once a beautiful sea nymph, transformed out of jealously through witchcraft. She first appears in Homer’s “Odyssey,” and is usually depicted with twelve legs and six heads, each with sharp teeth. Lurking in the shade of a fig tree on a rocky outcrop, she would snatch sailors from the decks the decks of passing ships. Her counterpart, Charybdis, is described as a treacherous whirlpool that swallows vast quantities of water three times a day, creating a vortex that could engulf entire ships and their crews.

In the “Odyssey,” the hero Odysseus encountered Scylla and Charybdis during his epic voyage home to Ithaca. He had to navigate between the two perils, choosing the lesser of two evils by steering his ship closer to “Scylla’s crag” and sailing past at top speed: “Better by far to lose six men and keep your ship than lose your entire crew” (Odyssey XII, 119 ff). This myth has become a symbol for the difficult choices we face in life, emphasizing the need to strike a balance between opposing dangers or challenges.

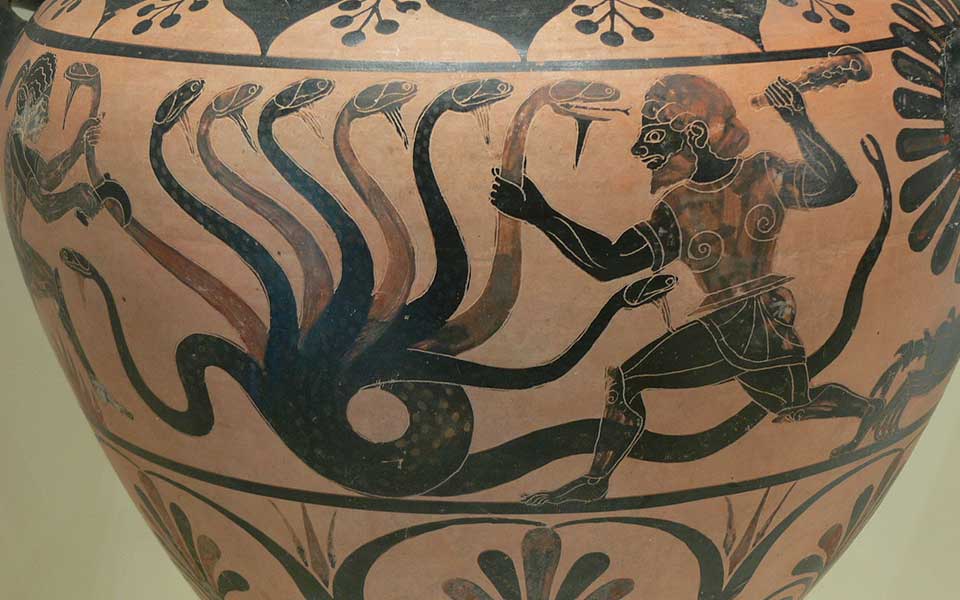

A Caeretan black-figure hydria (c. 346 BC), depicting Heracles and his nephew Iolaus slaying the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra.

© Public domain

The Lernaean Hydra

The Lernaean Hydra is a fearsome, multi-headed serpent-like monster that dwelled in the swamp near Lake Lerna in the northeast Peloponnese. Its most distinctive feature was its terrifying regenerative ability – for every head that was severed, two more would grow in its place.

The Hydra was one of the many offspring of Typhon and Echidna (see below), and the objective of the second of Heracles’ Twelve Labors. Accompanied by his loyal nephew Iolaus, the hero engaged in a relentless battle with the monster at the edge of the dark swamp. Realizing the challenge, he used a burning club to cauterize each neck stump after decapitating each head, thus preventing regeneration. Heracles eventually overcame the Hydra by decapitating all the heads and burying the last, immortal head under a massive rock – the creature was invulnerable as long as it retained one head. After the battle, Heracles dipped his arrows in the its poisonous blood, which he later used to kill other beasts during his remaining labors.

The Lernaean Hydra is often interpreted as a symbol of the seemingly insurmountable obstacles in life and the need for creative problem-solving to overcome them. Heracles’ victory over the Hydra exemplifies his resourcefulness and strength, making it one of the most iconic tales in Greek mythology.

"Odysseus and the Sirens," eponymous vase of the Siren Painter, c. 475 BC.

© Public domain

"The Siren" (1900), by John William Waterhouse (1847-1917).

© Public domain

The Sirens

Enchanting, seductive, deadly, the Sirens are often portrayed in Greek mythology as beautiful nymphs with the upper bodies of women and the lower bodies of birds. They are known for their mesmerizing songs, which they would use to lure sailors to their doom. The Sirens reside on rocky cliffs along perilous coastlines, where their songs are said to be so irresistible that passing sailors become entranced, steering their ships towards the treacherous rocks.

The most famous encounter with the Sirens is found in Homer’s “Odyssey,” when the hero Odysseus orders his crew to plug their ears with beeswax to resist the allure of their singing. Curious to hear their songs himself, Odysseus has himself tied to the ship’s mast, ensuring that he cannot act on the Sirens’ beautiful yet deadly call.

The Sirens symbolize the dangers of temptation, the allure of the unknown, and the consequences of succumbing to one’s desires. Their myth is a timeless representation of the struggle between reason and desire, and the perils of unchecked curiosity.

The "Chimera of Arezzo," an Etruscan bronze, c. 400 BC. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence. The Chimera represents the embodiment of chaos and the relentless destructive forces of nature.

© Public domain

The Chimera

The Chimera has to be one of the most bizarre looking creatures in Greek mythology, depicted as a monstrous hybrid with the body, head and mane of a lion, the head of a fire-breathing goat arising from its back, and a serpent’s tail. Its name is derived from the Greek word “khimaira,” meaning “she-goat,” and it was a symbol of pure, unfettered chaos.

The Chimera dwelled in Lycia, Asia Minor, terrorizing its inhabitants and causing destruction wherever it roamed. It was considered a fearsome and nearly invincible adversary. The hero Bellerophon, aided by the winged horse Pegasus, was tasked with defeating the Chimera. With help from the goddess Athena and a lead-tipped spear, Bellerophon managed to fly close to the creature on the back of Pegasus and drive the spear into its goat-head, ultimately defeating it.

This myth highlights the virtue of heroism and the triumph of order and reason over seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Echidna sculpture (1555) by Pirro Ligorio (1512-1583). Parco dei Mostri, Lazio, Italy

© Public domain

Echidna, the “Mother of All Monsters”

Another lesser-known creature is Echidna, an enigmatic beast often referred to by the ancients as the “Mother of All Monsters.” She is described as half-woman, half-serpent, combining the upper body of a beautiful nymph with the lower body of a coiling snake. Echidna’s origins are varied in different myths, but she is commonly associated with the sea monster Ceto and her husband Phorcys.

According to the epic poet Hesiod, Echidna was notorious for giving birth to a myriad of monstrous offspring, making her a central figure in Greek mythology’s pantheon of fearsome creatures. Her brood included the Chimera, the Sphinx, the Nemean Lion (of Heracles fame), the Lernaean Hydra, and at least half a dozen other creatures that terrorized ancient Greece.

Despite her offspring, Echidna herself isn’t typically portrayed as malevolent or actively harmful. Rather, she serves as the primordial source of many of the other mythological monsters. Her role underscores the Greeks’ fascination with the duality of beauty and horror, as well as their penchant for exploring the boundaries between humanity and monstrosity.

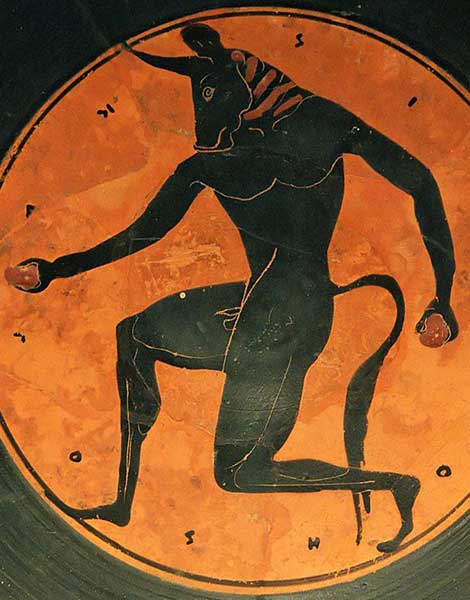

The Minotaur myth represents the theme of sacrifice and heroism in the face of adversity.

© Public domain

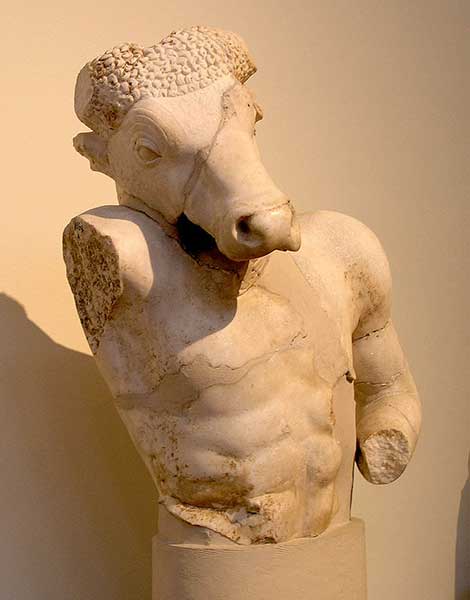

Marble statue of the Minotaur, found in Athens. Roman copy of an early Classical statue.

© Public domain

The Minotaur

The Minotaur is perhaps one of the best known figures from Greek mythology, a fearsome creature with the head of a bull and the body of a man. It was born from a union between Queen Pasiphae of Crete and a majestic bull sent by the sea god Poseidon, a result of a divine punishment. King Minos, Pasiphae’s husband, ordered the construction of a labyrinth to house the Minotaur, located beneath his palace at Knossos.

The Minotaur’s insatiable appetite for human flesh led to the annual sacrifice of 14 young noble Athenians (seven young men and seven maidens), who were sent into the labyrinth as offerings. Theseus, a young would-be hero, volunteered to be part of the group and, with a ball of thread, given to him by the king’s daughter, Ariadne, navigated the labyrinth and ultimately defeated the Minotaur, liberating Athens from this terrible tribute.

Marble sphinx statue from Spata, Attica, c. 570 BC.

© Shutterstock

The Sphinx

In the Greek tradition, the enigmatic Sphinx is often portrayed with the body of a lion, the wings of a bird, and the head of a woman (in contrast to ancient Egyptian mythology, where it was typically depicted as a man). A guardian figure, the Sphinx was renowned for posing mind-bending riddles and devouring those who failed to answer correctly.

In the most famous myth featuring the Sphinx, she terrorized the city of Thebes, perched near its gates, posing a riddle to passersby: “What creature has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?” Those who failed to solve the riddle were devoured. It was the tragic hero, Oedipus (unwittingly killed his father and married his mother…), who finally unraveled her enigma by answering, “Man, who crawls on all fours as a baby, walks on two legs as an adult, and uses a cane in old age.” Stumped, the Sphinx met her demise.

The story of the Sphinx symbolizes the unpredictable nature of fate and the significance of wisdom and cleverness. Her myth is a compelling testament to the power of human intellect in overcoming challenges and uncovering truth.

"Medusa," by Caravaggio (c. 1597)

© Public domain

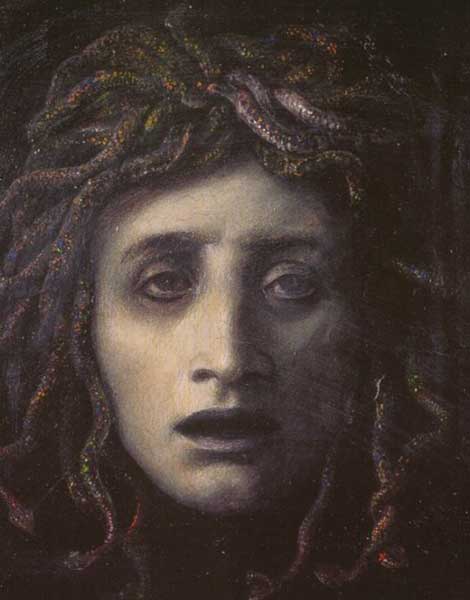

"Medusa," by Arnold Böcklin (c. 1878)

© Public domain

The Gorgon Medusa

Medusa, one of the three Gorgon sisters (Stheno and Euryale being the other two), is perhaps the most famous mythical creature of them all. She was once a beautiful mortal woman with long, flowing hair, “most wonderful of all her charms,” according to the Roman poet Ovid. However, she caught the eye of the sea god Poseidon and incurred the wrath of the goddess Athena. As punishment, Athena transformed her into a hideous creature with snakes for hair, a petrifying gaze, and great boar-like tusks.

Medusa became a symbol of terror and grotesque monstrosity, her gaze turning anyone who looked upon her into stone. Her severed head, which retained its petrifying power even after her death, became a potent weapon used by the hero Perseus.

Perseus, guided by Athena, managed to decapitate Medusa while she slept and later used her head to defeat foes, including the sea monster Cetus (not the Kraken!). This myth illustrates the ideal of heroism in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges and the transformative power of the gods. To this day, Medusa’s image remains an enduring symbol of both horror and fascination.