For a long time now, whenever we’ve found ourselves walking down Vasilissis Sofias Avenue past the Hilton Hotel and then stopping at the traffic light where the road becomes Vasileos Konstantinou, our eyes have automatically traveled upwards to the crane towering above the worksite of the National Gallery, and we’ve wondered: “When will it be done?”

Today, after so many years, we can say that we’re almost there. The renovation and expansion of the Greek National Gallery is in its final stages and, if all goes to plan, the new building will be unveiled on March 24, 2021; the day before the 200th anniversary of the start of the Greek War of Independence.

© Vangelis Zavos

© amna.gr/Ministry of Culture and Sports

In its new incarnation, the National Art Gallery joins the ranks of the other great cultural institutions the Greek capital has welcomed in the past 12 years.

The Acropolis Museum, the Onassis Cultural Center, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (home to the Greek National Opera and the National Library of Greece), the B&E Goulandris Foundation Museum of Modern Art, the National Contemporary Art Museum, and now the National Gallery make up the sextet of Athens’ new cultural stars.

Let’s start at the beginning: The National Art Gallery was founded in 1900. Today, it boasts a collection of more than 20,000 paintings, sculptures and engraving dating from post-Byzantine times to the present.

Its official name is the National Art Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum, reflecting the 1954 endowment of works from the lawyer and art lover. In the 1960s, the architects Pavlos Mylonas and Dimitris Fatouros designed a new National Art Gallery building that opened officially on Vasileos Konstantinou Avenue in 1976.

© Vangelis Zavos

© Vangelis Zavos

The work to modernize and expand the building designed by Mylonas and Fatouros began in 2013. Now, eight years later, the gallery is ready to reopen its doors to the capital’s art enthusiasts.

What was once a 9,270 square-meter building now offers 20,760 square meters, (with 2,230 square meters of that representing new exhibition areas where up to 1,000 pieces from its permanent collection can be displayed – compared to just the 400 pre-renovation). An amphitheater will accommodate up to 450 people, and there will be two bar-restaurants as well, one with a stunning views stretching from Lycabettus Hill and the Acropolis all the way down to the Saronic Gulf.

These are just numbers, of course, and tell us little about whether this renovation will be deemed a success or not. Apart from comments such as “impressive,” “iconic” and “modern,” we’ve also heard the usual complaints about “maximalist” ambitions and some disapproval of the choice of the large glass panes that will go on its façade, with critics saying they will turn the building into an enormous mirror during the day.

But there’s nothing unusual about such negative comments; they accompany every major project in every part of the world and are, in fact, an intrinsic part of the public debate that accompanies such interventions. Whether the new National Art Gallery has hit the mark, whether it has brought about a successful marriage of Greece’s art heritage with modern museological approaches and technology, and whether it will become a landmark embraced by the city and its visitors is something that only time will tell.

For now, we look forward to the exhibition on the Greek Revolution that will be unveiled at the March opening and, of course, cannot wait to see the work of all the great artists represented in the institution’s permanent collection, from Dominikos Theotokopoulos (better known as El Greco), Nikolaos Gyzis, George Iakovidis and Theophilos Hatzimihail to Konstantinos Parthenis, Nikos Engonopoulos, Yannis Tsarouchis and Panagiotis Tetsis.

Apart from the great Greeks, the National Gallery also has a sizeable collection of works by great western European painters, such as Goya, Rembrandt and Durer.

Here is a selection of 15 representative works of Greek painters that we will have the opportunity to admire up close in the new exhibition spaces of the National Art Gallery:

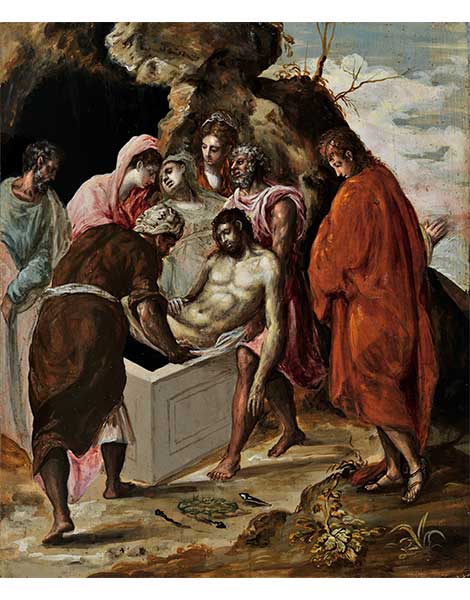

“The Entombment of Christ,” ca. 1568-1570, 51.5×42.9cm, oil and tempera on wood.

Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco) (1541-1614) was born in Venetian-occupied Iraklio on Crete where he worked as a hagiographer before moving to Venice and later to Spain. Although well received as an artist during his lifetime, he was considered by all to be different from his peers. The great pioneers of the 20th century, including artists such as Cézanne, Picasso and Jackson Pollock, found in him an inspiration for their own subversive approaches to painting.

“The Army-Camp of Karaiskakis,” 1855, Oil on canvas, 145x178cm.

Theodoros Vryzakis (1814-1878) son of a revolutionary fighter who was hanged during the Greek War of Independence, attended the Greek School in Munich and won admittance to that city’s Academy of Fine Arts. He followed the classical romantic spirit and remained faithful to the tenets of academic realism associated with the Academy, all while working with subjects that included the revolutionary struggle and the founding of the Greek state.

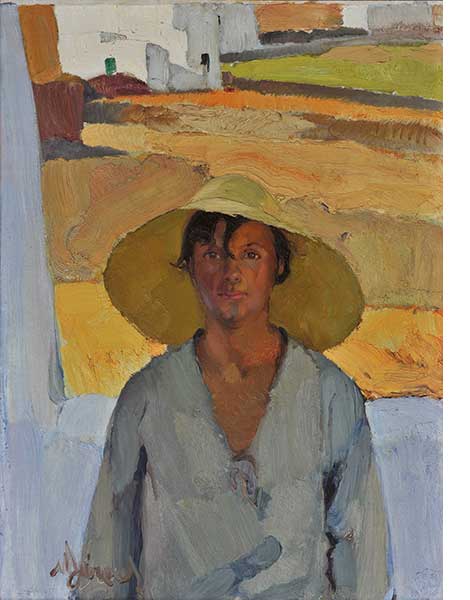

“The Straw Hat,” 1925, Oil on canvas, 86x66cm.

Nikiforos Lytras (1832-1904) was the main representative of what became known in Greece as the School of Munich, a school of painting adopted by those 19th-century Greek artists who had studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. A number of those Greek artists settled in Germany, taught and worked there, but Lytras returned to his homeland and taught at the Athens School of Fine Arts. He is considered the father of modern Greek painting and, although his choice of subjects was wide-ranging, the most important of his works were in all probability those involving folk traditions, scenes of everyday urban and rural life, depictions of the Greek family and works with distinct Orientalist elements.

“On the Jetty,” 1869-1875, Oil on canvas, 70x45cm.

Konstantinos Volanakis (1837-1907) was perhaps the most important Greek marine artist. He spent much of his life in ports, including Ermoupoli on the island of Syros, where he went to school; Trieste, where he worked as a young accountant; and Piraeus, where he died, penniless. The sea was the focus of his work: ships, boats, naval battles and scenes from everyday life in the ports.

“Wishbone,” 1878, Oil on canvas, 46x37cm.

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901) was one of the great figures in Greek painting; he spent most of his long, successful career in Munich. His later work is marked by the questioning approach that characterizes the pioneering Jugendstil movement.

“Cold Shower,” 1898, Oil on canvas, 89x100cm.

George Iakovidis (1853-1932) was the first director of the National Gallery and one of the foremost representatives of academic painting in Greece. In his works, we find mythological and ethnographic scenes, portraits, still lifes and landscapes. His most interesting compositions, however, are scenes of childhood, which he depicted both playfully and with great sensitivity.

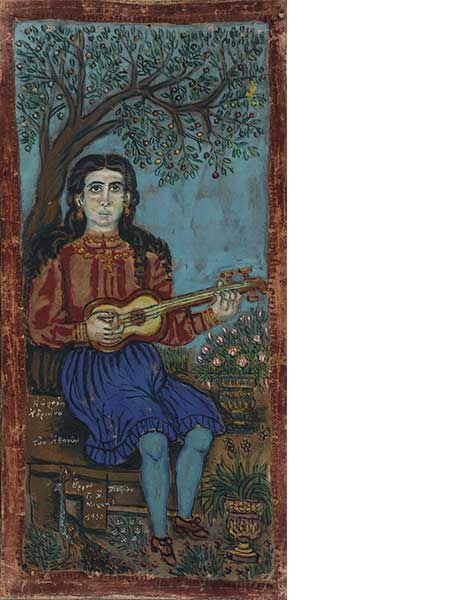

“The Beautiful Adriana of Athens,” 1930, oil on canvas, 92×43.5cm

Theophilos Hatzimihail (1873-1934), better known simply as Theophilos, was perhaps the most idiosyncratic self-taught artist in the history of Greek painting. Largely unheralded during his lifetime, he earned his living painting murals and signs for inns and coffee houses. His work displays all the innocence and exuberance of folk art.

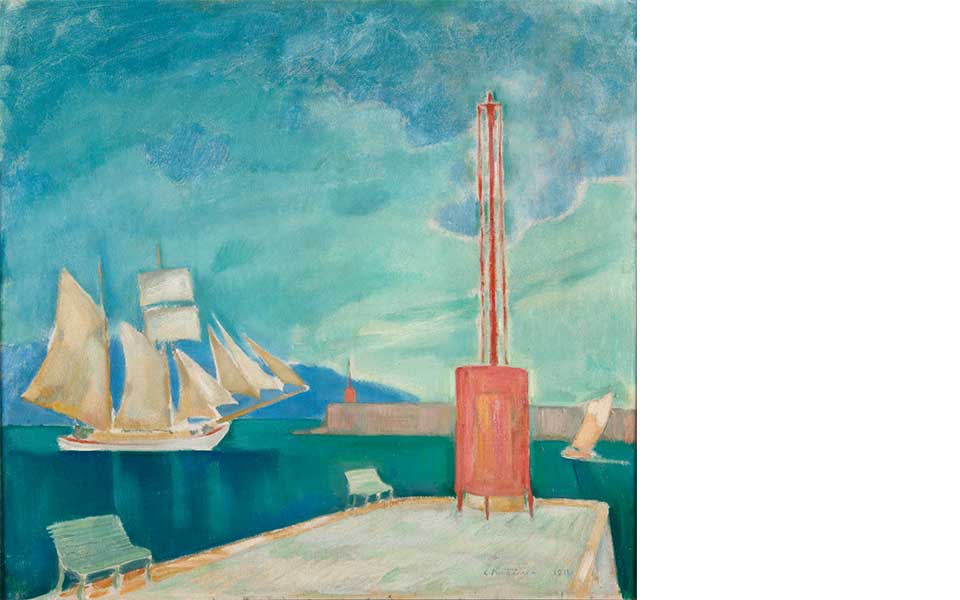

“The Harbor of Kalamata,” 1911, Oil on canvas, 70x75cm.

Konstantinos Parthenis (1878-1967) represents a rupture with the academic realism of the Munich School. A cosmopolitan and a modernist, he was influenced by Domenikos Theotokopoulos, the Viennese Secession, early Cubism and the French post-impressionists. In his mature works, he combined all these influences into a strongly personal style, depicting an idealized Greece where light and harmony prevail.

“Dancers,” 1936, Oil on canvas, 140x119cm.

George Bouzianis (1885-1959) is the most important Greek representative of expressionism. During the years of his stay in Germany, he experimented with all the permutations of the expressionist movement to create his own authentic personal style. In his work, he uses color as a basic structural element to express deep emotional conflicts in a way that foreshadows principles of abstract art.

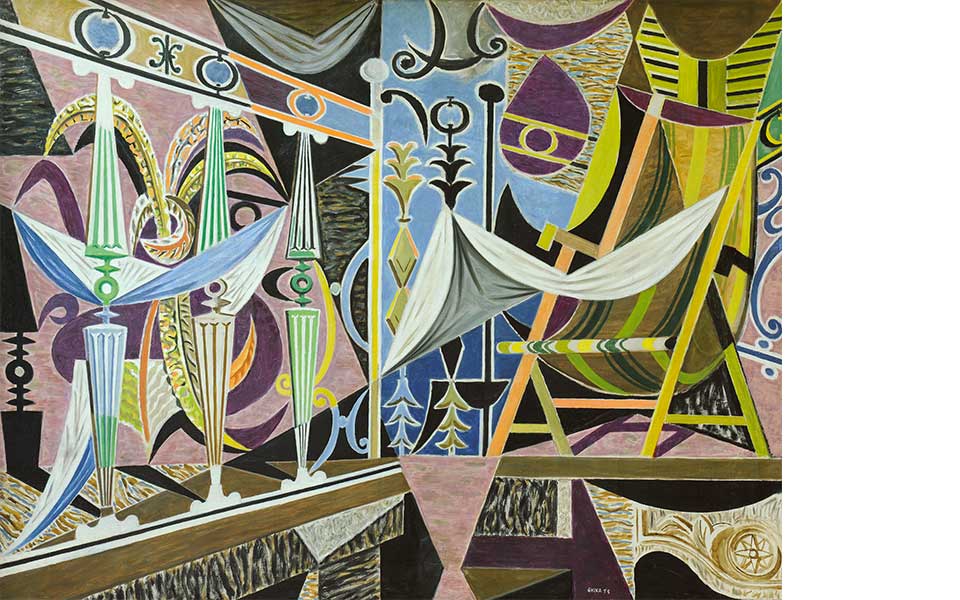

“Athenian Balcony,” 1955, Oil on canvas, 115x146cm.

Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas (1906-1994), also known as Niko Ghika, was a worldly and intellectual artist who managed to combine elements of European Cubism and traditional Greek art to create his own personal idiom.

“Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletos,” 1970, Oil on canvas, 55×44.5cm.

Nikos Engonopoulos (1907-1985), painter, set designer and poet is the main representative of a peculiar version of surrealism in Greece. Unconventional and subversive, it combines elements of traditional Greek art with the irony, humor and eroticism of the European avant-garde.

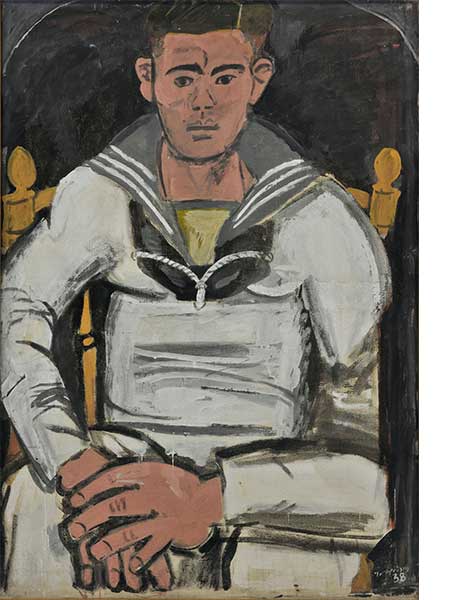

“Sailor,” 1938, Oil on canvas, 100x70cm.

Yannis Tsarouchis (1910-1989), one of the most important figures in the art movement known as the Generation of the ’30s, combined elements of ancient Greek painting, Byzantine iconography and folk art to produce work that is regarded today as ideally Greek.

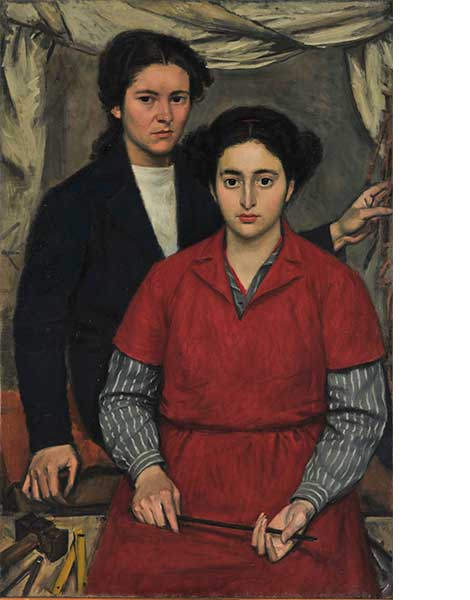

“Two Girl Friends,” 1946, Oil on canvas, 100x67cm.

Yannis Moralis (1916-2009) was a major influence on the post-war art scene in Greece, not only in his artistic work and his long-term teaching career at the School of Fine Arts but also in his important collaborations in fields such as set design, architecture and ceramics. He exhibited an ability to marry the classical with the modern and imbue the result with radiant Mediterranean humanism.

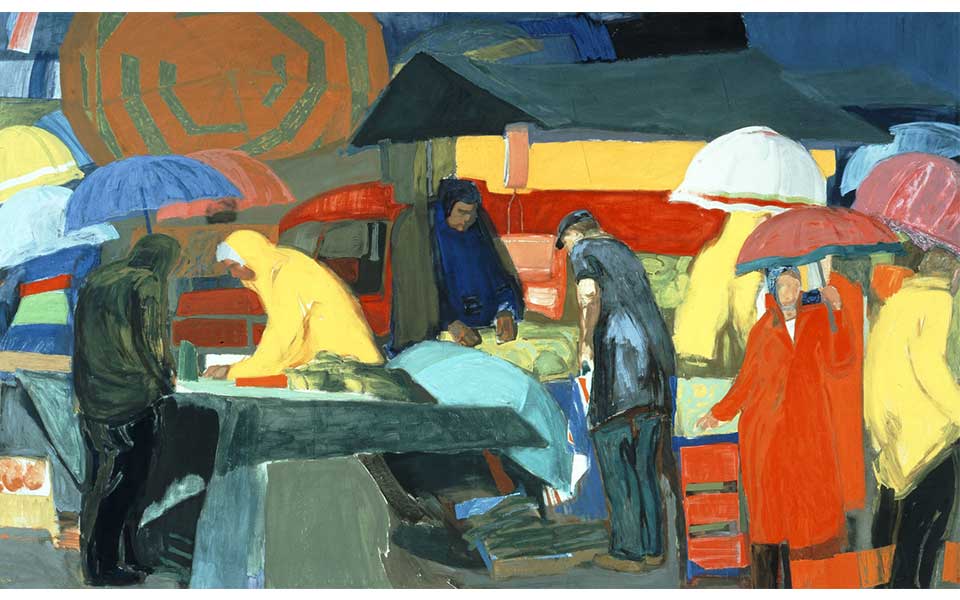

“Street Market,” 1979 – 1982, Tempera on canvas, 249x405cm.

Panayiotis Tetsis (1925-2016) was an artist beloved by the Greek public, a painter who stayed faithful for most of his working life to representational art and to expressionism. In his work can be found a passion for Greek landscapes and for the special light of Greece, as well as a childlike curiosity he held for the world around him.

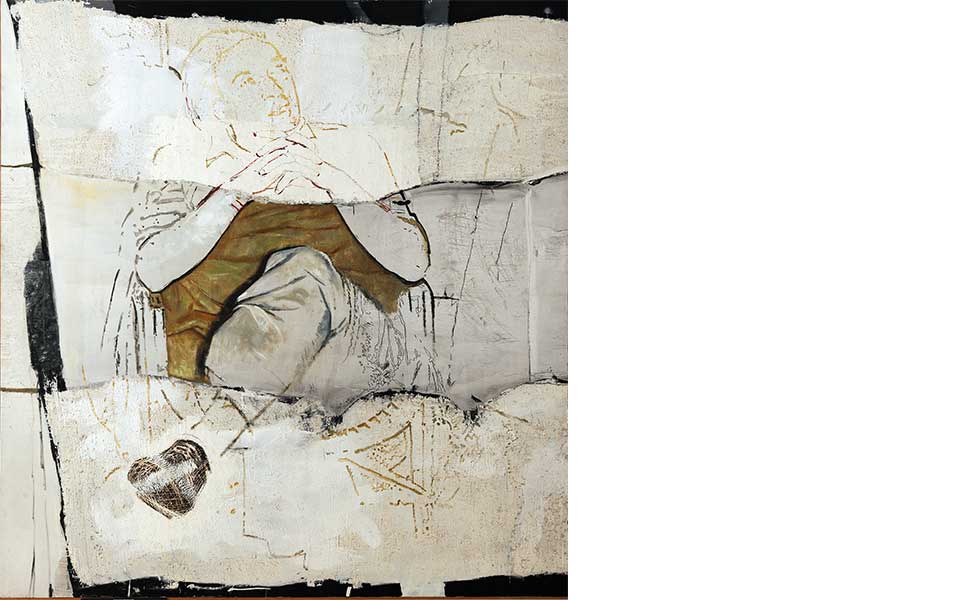

“Portrait of Dinos Georgoudis,” 1976, Mixed media on canvas, 200x199cm.

Nikos Kessanlis (1930-2004), a representative of a post-war generation that questioned everything, matured artistically in the Europe of the 1960s. Working in Rome and Paris, he joined the art critic Pierre Restany and the Mec-art movement. Kessanlis managed to stay at the forefront of the European avant-garde for over thirty years. Creatively restless and iconoclastic, he never stopped experimenting, passionately exploring his means of expression.