Ιn Crete, it’ s not only the magnificent artifacts and layers of archaeological remains that illuminate the island’s successive waves of human inhabitation and eons-old culture; it’s also a collection of divine or heroic characters and richly-narrated, locally-born legends, whose origins appear to be rooted, in many cases, back in the darkest depths of Minoan prehistory.

More than 2,000 years ago, Crete’s colorful mythology had already spread far beyond its own shores. Today, people around the world continue to find the stories of ancient Cretan gods, goddesses and heroes intriguing and meaningful – a timeless treasure trove to be cherished for all the delightful details and insights they provide about life, religion and the natural world in ancient Crete.

© Vangelis Zavos, Ministry of Culture and Sports/Heraklion Archaeological Museum

POWERFUL FEMALE DEITIES

Women in ancient Crete clearly played a central role in religion and society. Modern archaeological museums are filled with extraordinary Cretan art works, produced by master artists in various media, which portray females as figures of particular power and respect. Foremost among these figures is the “Mountain Mother” or “Mistress of Animals,” a Minoan nature goddess, who frequently shows up on small, finely-cut seal stones, gold jewelry and ivory-carved cosmetic cases, often flanked by two lions, griffons or wild goats. A more urban or domestic figure – either a specific goddess (perhaps of the household) or a prominent priestess – is the Snake Goddess (ca. 1600 BC), first discovered by Sir Arthur Evans at the Palace of Knossos. At Gazi, Knossos and numerous other sites, the “Poppy Goddess” and similar figurines with upraised arms and open palms were typical of Mycenaean-dominated (post-1450 BC) Crete and may have represented a deity who induced sleep and death.

The powers of female fertility and procreation are celebrated in Cretan art from earliest times, with Neolithic figurines of the 5th millennium BC depicting curvaceous, fecund women. Similar female strengths are embodied in the being known as “Eleuthia,” named in a Linear B text discovered at Knossos, who centuries later appears as Eileithyia, the daughter of Zeus and Hera and Homer’s goddess of childbirth. Eileithyia was worshiped in a sacred cave near Amnissos, a port of Knossos, as well as at the Cretan sites of Lato, Eleutherna and Itanos. At Delphi, a stone altar in the small sanctuary of Athena Pronaia is inscribed with her name, while in Delos she was said to have aided Leto during the birth of Apollo and Artemis.

With the rise of the Geometric and Archaic Greeks’ now-well-familiar pantheon of gods and goddesses by at least the 8th or 7th centuries BC, the identity of prehistoric Crete’s main female deity came to be equated with various figures – including Homer’s Artemis Agrotera (“Potnia Theron”), also a goddess of animals and the wild; Rhea/Cybele, daughter of Gaia and Uranus, originally an Anatolian mother goddess recognized on Crete as the mother of Zeus, who many believed was born on the island; and Britomartis, whose name (“Sweet Maiden”) may have been an intentional, apotropaic misrepresentation of her otherwise wild, sometimes daemonic nature.

Britomartis, also known as Diktynna, was viewed as a distinctly Cretan form of Artemis, a huntress, bestowed with powers of fertility, life, death and resurrection. Her temples, reputedly guarded by fierce dogs, were found both in Crete and abroad – in Athens, Sparta, near Delphi and on the island of Aegina (perhaps here, as elsewhere, through the influence of Cretan traders or immigrants), where she was worshiped as Aphaia. In Crete, Britomartis/Diktynna was especially prominent at Olous (modern Elounda), where Pausanias reports there was a wooden cult statue (xoanon), as well as in and around Kydonia (present-day Hania), according to the geographer Strabo.

TALES OF MINOS

Supreme among the mythical figures of Iron Age Crete was King Minos of Knossos, who appears in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Following Evans’ early-20th c. investigations of the Palace of Minos, “Minoan” became a standard archaeological term referring to Crete’s tripartite Bronze Age civilization (ca. 3000-1100 BC). Although females continued to feature prominently in art and literature, the male figure of Minos emerged as a central personality linked to many vivid characters and secondary myths. Minos, the son of Zeus and the Phoenician princess Europa (another Cretan connection to the East), married Pasiphae (“All-Shining”), daughter of Helios (Sun). Their offspring included a daughter, Ariadne.

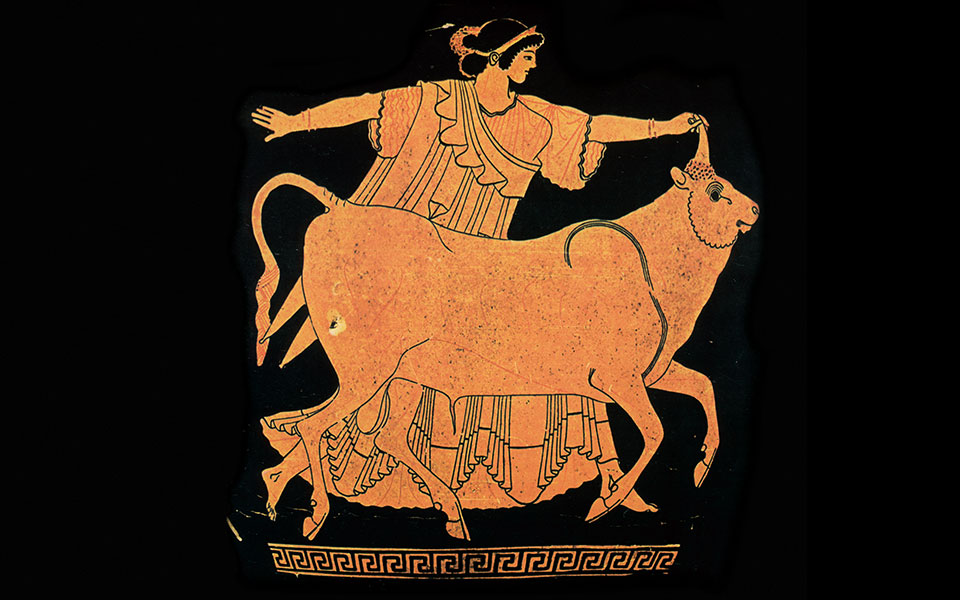

Certain details of Minos’ tales seem almost to be shadowy reminders of traditions and beliefs from prehistoric times. Bulls and the double-headed axe (labrys) were distinctive features of Minoan Cretan religion or ritual, but they also appear in Minos’ mythical world. Europa was borne from Tyre to Gortyn by Zeus disguised as a bull, while Pasiphae (Europa’s daughter-in-law) was induced by Poseidon to fall in love with an impressive sacrificial bull he had provided to Minos. The strange fruit of the latter pair’s passions was the monstrous Minotaur (a man with a bull’s head), whom the king caged within the central courtyard of his labyrinth-like palace. In considering the inspiration behind Minos’ labyrinth, classicist H. J. Rose comments that, in post-Bronze-Age years, some of Knossos’ architectural remains “were probably above ground long enough to bewilder and puzzle the early Greeks, themselves accustomed to much simpler dwellings…” Pasiphae’s bull, also called the Cretan Bull, became the subject of Heracles’ seventh labor, after the animal, destructively raging around the island, was judged to be a menace. Heracles subdued the bull with his bare hands, then sent it back to King Eurystheus of Tiryns.

Cretan relations with Athens may find representation in the figures of Daedalus and Theseus. Daedalus, an Athenian and the “most cunning of all craftsmen,” had fled to Crete to avoid a murder charge. There, he was employed by Minos and later by Pasiphae, who sought his assistance in attracting her bovine paramour. He ingeniously disguised her inside a faux-cow. Minos, too, had a wandering eye; another myth relates that, to elude his advances, Britomartis jumped off a cliff into the sea (Callimachus, Ode 3). She landed in a fisherman’s nets (diktya), thus earning the Kydonian title “Diktynna” (Lady of the Nets), before fleeing to Aigina.

Daedalus was sometimes identified as the designer of Minos’ labyrinth/palace, but he, like the Minotaur, was made a prisoner inside it, along with his son Icarus, either to prevent him from sharing its secrets or as punishment for aiding the queen in her infidelity. To escape, Daedalus invented feather-and-wax wings. Together, he and Icarus flew away, but the son recklessly ignored his father’s warnings and flew too near the fiery sun, only to have his wings melt. He plunged to his death in what henceforth would forever be known as the Icarian Sea.

Theseus, the archetypal Athenian hero, also appears in Crete, after Minos’ son Androgeos, a talented athlete, was enviously murdered by his defeated Athenian competitors. Minos, outraged, demanded a compensatory tribute of fourteen male and female Athenian youths be paid to Knossos periodically; these unfortunate youths were devoured by the Minotaur. One year, Theseus, son of King Aegeus of Athens, joined their ranks and journeyed to Crete with the intent of killing the Minotaur. At Knossos, he recruited the aid of Princess Ariadne, who had fallen in love with him. She showed him how, using a ball of thread, he could retrace his steps through the maze-like palace. After successfully slaying the monster, Theseus added insult to injury by escaping from Knossos and stealing Ariadne away, only to later abandon her on a beach on the island of Naxos.

THE INFANT ZEUS

A divine child was another age-old figure of worship for Cretans. Whether direct continuity existed between the “Minoan Young God” or other Bronze Age deities and the gods of subsequent eras remains, however, a much debated subject among specialists. Increasingly, it has been suggested that post-Bronze Age beliefs in Crete developed separately, with only minimal inspiration or influence from previous traditions.

Zeus, in the eyes of Iron Age mythographers epitomized by Hesiod (8th c. BC), was born and/or secretly cared for in a cave either on Mt Ida, according to the Theogony, or on Mt Dikti (respectively, SW and SE of Irakleio). Rhea hid baby Zeus from his Titan father Cronus, who, for fear of being usurped as king of the gods, had already swallowed all of Zeus’ siblings. Present-day archaeologists exploring the Idaean and Dictaian/Psychro Caves have discovered shrines and dedicatory offerings at both sites which date back to the Minoan period.

Sequestered in his lofty cave, Zeus was watched over by nymphs, led by the nurturing Amaltheia (some myths depicted her as a wild she-goat instead) who fed him draughts of goat milk from an inexhaustible horn – a purported antecedent for the symbolic Cornucopia (Horn of Plenty). He was also raised on mountain honey, either dripped directly into his mouth by bees or administered by another nymph, Melissa (“bee” in Greek), who was credited in Crete with having first learned and disseminated the art of bee-keeping and honey production.

To further protect Zeus, Amaltheia recruited a band of nine spear-bearing warriors, the Kouretes (or Korybantes), followers of Rhea/Cybele who danced around, rattling their armor and beating on their shields as loudly as possible at the cave’s mouth in order to cover the sound of the infant god’s cries. The Kouretes, like the Mountain Mother, the Mistress of Animals, Rhea/Cybele and the mysterious Idaean Daktyloi, are all mythical reminders of Crete’s ties with the East – evident archaeologically since prehistoric times. The Daktyloi were six giant blacksmiths and magicians, also associated with Rhea, who inhabited Mt Ida and were sometimes said to have sprung from dust thrown by one of Zeus’ attendant nymphs. On reaching manhood, Zeus challenged his father, making him regurgitate his brothers and sisters – Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades/Pluto and Poseidon – and then installed himself as ruler of the Heavens and king, or greatest among equals, on Mt Olympus.

RITES OF PASSAGE AT PALAIKASTRO

Zeus was worshiped in Crete in various forms, one of which is revealed by a fragmentary inscription discovered at the eastern site of Palaikastro. The text – a Roman copy (2nd-3rd c. AD) of an earlier text dating back, based on its language, to at least the late Classical or early Hellenistic eras (4th-3rd c. BC) – was the “Hymn of the Great Kouros.” Scholars have concluded it was part of a ritual coming-of-age or initiation ceremony that involved adolescent Cretan males who, through performances involving dancing and clashing of weapons, celebrated the maturing Dictaian Zeus by evoking his mythical guardians, the Kouretes.

CRETAN “IRONMAN”

With all the robot-like characters described in ancient Greek literature, one might wonder if the “aliens-in-antiquity” theorists are right in thinking a race of extraterrestrial robots once visited Greece, passing on their engineering skills and leaving a lasting impression on local legends. Even Homer (Iliad 18.371-379) refers to golden-wheeled tripods crafted by Hephaestus that could “enter the gathering of the gods at his wish and again return to his house…” Plato, too, has Socrates repeat an old legend that Daedalus created automatons (Meno 97d), which, if not fastened up, played truant and ran away, but, if fastened, would stay where they were.

One of the stranger mythological characters of Crete is the island’s gigantic bronze guardian Talos. Apollonius of Rhodes (Argonautica, 3rd c. BC) writes: “A descendant of the brazen race that sprang from ash-trees, he had survived into the days of the demigods, and Zeus had given him to Europa to keep watch over Crete by running round the island on his bronze feet three times a day.” This automaton, whose creator was either Hephaestus or Daedalus, was known from at least Classical times, when vase paintings (ca. 400 BC) depict his death. Talos’ one weak point (like that of Achilles) was his ankle, where a nail closed his single vein. When Jason sailed toward Crete, having obtained the Golden Fleece, Talos hurled rocks at the Argo, but was killed by the sorceress Medea. Through either magic or mendacity, Medea caused the nail to be pulled out, according to Pseudo-Apollodorus (Bibliotheke, 1st/2nd c. AD), and Talos lost all his essential “ichor” (immortal blood). From the perspective of present-day robotics, he suffered a terminal oil leak.