Although continuously inhabited for at least 28 centuries, Kastellorizo has a fitful archaeological record: some periods are well represented, while others have left little or no trace.

The island’s past offers us something larger, however, as archaeologist Fotini Zervaki of the 22nd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities observes: “It reflects the important geographical position and the economic and strategic significance of the entire region.”

In the millennia-long, pre-modern age of the sailing ship, the island found itself in the midst of an all-important sea route along the southern Anatolian shore which connected the East with the West. It also lay at an interface between Greek civilization and the distinct cultures of Asia Minor. As a result, it was consistently exploited as a military and commercial base, a key maritime port-of-call.

Its history of fluctuating fortunes is a direct result of its attractiveness to outside powers. Kastellorizo flourished, comments Zervaki, especially “when some central authority needed organized control over the sea passages.”

© Nikolas Leventakis/Archaeological Museum of Kastellorizo/MInistry of Culture & Sports, Prefecture of Dodecanese

By Any Other Name…

The name “Kastellorizo” inspires visions of an island fortress. Indeed, its distinctive, time-worn defenses on the northeast coast gave rise to its current appellation – a Greek corruption of the medieval Italian “Castello Rosso” (“Red Castle”).

From the 12th century, Castello Rosso became a familiar place for early travelers, traders and adventurers. Prior to the arrival of Venetian and other Italian merchants, Kastellorizo had been known as Megiste (or Megisti) in ancient Greek – as we know both from historical sources and an inscription, first discovered by Charles Cockerell during his 1812 visit, carved into the rock below the castle.

Megisti first appears in ancient literature around 330 BC, when the island, along with various Lycian coastal cities and ports of call, is mentioned in a navigational guide by Pseudo-Skylax: “Telmissos…Xanthos…Patera…Phellos…; off these places is an island of the Rhodians, Megiste.”

The Roman historian Livy describes the naval importance of Megisti’s port during Rome’s struggle against Antiochus III, Macedonian king of the Seleucid Empire, in the Fourth Syrian War (190 BC). Although the Rhodians supported the Romans, one of their admirals, Polyxenidas, had gone over to the Macedonians. Faced with Ephesus’ eventual surrender, Livy recounts, Polyxenidas set sail for Syria, but was so wary of the Rhodian fleet stationed at Megiste that he landed west of the island at Patara and continued his eastward journey by land.

© Nikos Pilos

Propitious Geography

The ancient name refers to Megisti being “the largest” island of the surrounding archipelago of 30 smaller islets and reefs.

Located about 130km east of Rhodes and about 2km from Anatolia, Megisti offered ships protection in several natural bays: a double harbor on its northeast side – today the main (Kavos) and smaller (Mandraki) ports – separated by Cape Kavos; and a third, western inlet, Limenari, useful when the winds shift. Inland, the mountainous terrain features three main peaks, Vigla (273m), Paliokastro (244m) and Mounta (230m), which likely were well-known landmarks for approaching sailors.

Lying outside the Aegean, Megisti/Kastellorizo represents the easternmost and smallest of the main Dodecanese Islands. Its proximity to the Lycian coastline, flanked by key maritime centers including Patara, Antiphellos (now Kaş), Aperlae and Myra, made the island a useful offshore base, a launching-off point for the mainland and an East-West gatekeeper.

© Nikos Pilos

Wanderers, Merchants and Naval Strategists

Prior to the dawn of the Neolithic era in the 7th millennium BC, Mesolithic people were already migrating between Asia Minor and the Aegean region, where the Dodecanese islands became stepping stones for both westbound and eastbound travelers. During Neolithic times, these wanderers became Kastellorizo’s first hunters, farmers and settlers, judging from sparse traces of chipped and ground stone tools.

By the Late Bronze Age, cultures and commerce had greatly advanced all around the eastern Mediterranean. Local and international traders were already plying the sea routes along the southern Anatolian shore – as indicated by two sunken sailing vessels of the late 14th and 12th centuries BC, discovered not far from Kastellorizo at Ulu Burun and Cape Gelidonya.

Prehistoric pottery fragments unearthed in Kastellorizo’s modern cemetery, on the small cape east of Mandraki, point to the possible existence there of a harborside settlement. During Geometric and Archaic times, the island’s residents occupied high Paliokastro, where representative pottery fragments are found.

Megisti’s fate during the Persian Wars remains uncertain, but Anatolian influence was clearly felt on the island, as shown by the Lycian tomb with its Ionic façade (late 4th c. BC) carved into the cliff below the later medieval castle. Greek war ships of the Delian and Athenian Leagues sailing to/from Persian-dominated Cyprus in 478 and 451 BC may have stopped over in Megisti for supplies.

The second half of the 4th century BC witnessed great development in Megisti. Its first fortress may have been built on Kavos, where a preexisting tower underlying the medieval castle can be distinguished by its distinct pyramidal base, datable to Late Classical/Early Hellenistic times. A multi-towered fortress was also erected on Paliokastro.

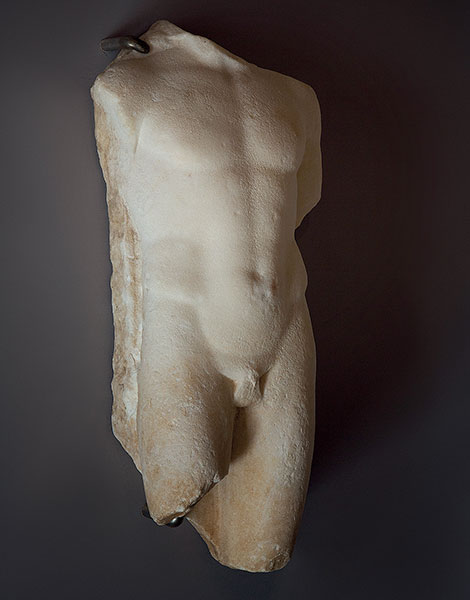

© Nikolas Leventakis, Archaeological Museum of Kastellorizo

Serving Mighty Rhodes

Megisti’s destiny became intertwined with that of powerful Rhodes during the Classical and especially Hellenistic periods. After founding Phaselis on the Anatolian coast in 690 BC, the Rhodians would naturally have exploited the island as a convenient way station en route to their new colony.

Pseudo-Skylax’s Late Classical reference to “Rhodian Megiste” confirms that Megisti had become an important naval base within the Rhodian Peraia. This Rhodian “empire” overcame external pressures from the Persians, the Hekatomnids of Halicarnassus, and Alexander the Great’s successors, eventually being acknowledged by Rome as a regional authority in the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC).

With Rhodes emerging as a major military and commercial sea power during the 3rd and 2nd c. BC, Megisti was designated the seat of an “epistates”: a resident Rhodian military commander of a garrison. Six epistates inscriptions have been found on the island, all reputedly of the 2nd c. BC.

Rome soon realized that Rhodes was an economic rival needing to be tamed. In 166 BC, the new free port of Delos began to eclipse Rhodes as a maritime trade center. Two years later, recognizing its fate under Rome, Rhodes signed a treaty accepting its new status as a “free and allied city.” With Megisti, it carried on as a key commercial base and naval station in the Roman East.

© Nikolas Leventakis, Archaeological Museum of Kastellorizo

© Nikolas Leventakis, Archaeological Museum of Kastellorizo

Megisti’s Archaeological Heritage

Although sparse, Megisti’s ancient archaeological remains, ranging from mountaintop towers to low reservoirs and sunken breakwaters, tell a tale of defense, industry and adaptation.

The epicenter of life was Megisti’s northeastern double harbor – now overlooked by the remains of the 14th c. Castle of the Knights of St. John – which seems to have functioned primarily for the sheltering, provisioning and repair of passing ships. No walled town existed on the island. Instead, a Late Classical/Early Hellenistic tower rose above the Kavos port, perhaps on the site of an earlier tower.

The main quarters for the island’s military garrisons may have been the large Paliokastro fortress (about 6,000 sq m). This strategic citadel had four bastions along its southeastern wall. An internal tower still stands about 4m in height. Ceramic evidence shows Paliokastro was probably also a pre-Classical acropolis.

On adjacent Mt Vigla, a 60m-long polygonal-masonry wall, previously characterized as “Cyclopean” and “Mycenaean,” may actually have formed part of the Rhodian garrison’s inland defenses, Zervaki contends, as “this type of masonry was quite common in Caria from the Classical until the Roman period.”

The Paliokastro fortress allowed a commanding view over Megisti’s northeastern ports, the western Limenari anchorage and the vital shipping lanes below. It represented the center of a network of smaller beacon towers located on the island, the islets of Ro and Strongyli and the Lycian coast opposite. Today, a modern lighthouse (1870) still marks the island of Strongyli; it has the distinction of being Greece’s easternmost building.

© Perikles Merakos

Ancient daily life is attested all around Kastellorizo by small, rural, fortified Hellenistic and Roman or Byzantine farmsteads. Wine-pressing and olive-crushing installations (pressing surfaces, collection basins) are found at these sites and in isolated spots. Amphorae and pithos (large storage jar) fragments date these production sites from Archaic through Roman times.

Many rock-cut cisterns, including nine large circular basins at Acheres west of the port, indicate rainwater was precious, while ancient wells exist only beside the main harbor near Aghios Georgios tou Pigadiou. Rock-cut graves are also common throughout the island, with particular concentrations at Kavos and near the Monastery of Aghios Georgios tou Vounou.

Goods traded through Megisti’s Hellenistic port included wine, oil, grain and Lycian timber. The island’s military and commercial facilities continued to be valued, with Roman authorities overseeing repairs to Paliokastro’s walls and installing breakwaters at Kavos and the islet of Psoradia opposite.

Amphorae fragments and other pottery on the seabed – probably broken refuse tossed overboard from anchored ships rather than shipwreck evidence – clearly signal Megisti’s ongoing maritime importance.

Saints, Saracens and Byzantine Defenders

Little is known of Megisti during Roman and Byzantine rule, prior to the arrival in the region of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in 1306. The population consisted mostly of farmers, maritime merchants and their families. Local products were mainly wine and olive oil, although various domestic and foreign goods would have passed through the port.

Ancient inscriptions reveal the islanders worshiped Zeus, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Demeter and the Dioscuri. Christianity probably came early to Megisti, spread by seaborne travelers. Foremost among these may have been St Paul himself, whose voyage from the Aegean to Jerusalem in AD 58 took him directly past Megisti.

Early Christian worship in Megisti is indicated archaeologically by the remains of a small chapel near the island’s double port, on the same site as the later Church of Aghios Georgios Malaxos or Psiphios (1637) and the current Church of Aghios Georgios Santrape (1904-1907).

Also early is the partly preserved mosaic floor of a chapel, later reused in the Katholikon for the Monastery of Aghios Georgios tou Vounou (18th c.). An inscription carved on an ancient pulpit now in the tiny Church of Aghios Georgios o Phtochoulis (unknown date) near Paliokastro suggests the pulpit once belonged to a (now-destroyed) chapel of Aghios Vasileios, perhaps built on the same site in Early Christian times. Local legend holds a small chapel was also established in the 4th century AD by the Empress Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, on the spot where the Church of Aghios Konstantinos and Aghia Eleni (1835), Kastellorizo’s revered patron saints, now stands.

With the onset of Arab raids in the 7th century, life on Megisti became less tranquil. Byzantine authorities used the island’s late-4th c. BC fortifications to defend the island against these Eastern marauders. In one incident, Rhodian records show that Byzantine ships set sail from there in 718 to repel an approaching Saracen fleet. In 807, an armada of the Caliph Harun-al-Rashin similarly threatened Rhodes, likely also troubling Megisti on its way.

© Nikolas Leventakis, Archaeological Museum of Kastellorizo

Merchants of Venice

Italian, particularly Venetian traders were a dominant force in the medieval eastern Mediterranean economy, already receiving permission in 1082 from Byzantium’s emperor to conduct their maritime business through Rhodes. Sea trade could be extremely profitable, but also risky, as fortunes might be made or lost depending on the successful completion of a commercial fleet’s voyage.

Following the Crusaders’ sack of Constantinople (1204), Rhodes enjoyed a certain independence and control over neighboring islands, probably including Megisti. Eventually pressed to resubmit to Byzantium, the local Rhodian ruler, Vignolo de Vignoli, instead sold the island to the Knights of St John. First attempting to take possession of Rhodes in 1306, the Knights remained unsuccessful until 1309; during this interval they may have used Kastellorizo as a forward base of operations.

The portside castle partly preserved today was first constructed around 1380, as revealed on the tower by a coat of arms belonging to the Aragon knight, Juan Fernández de Heredia (then Grand Master of the Knights of St. John). It was largely destroyed in 1440, and rebuilt in 1450. Castello Rosso’s fortifications and other infrastructure are described by early travelers, who mention towers, bastions, turrets, a cistern, a courtyard and a drawbridge.

Kastellorizo now found itself at the edge of a highly sophisticated cultural sphere during the Middle Ages, especially by the end of the 15th century, as European Renaissance tastes filtered through from the West. Kastellorizo was again influenced by Rhodes, a renewed center of art, architecture, literature and learning. The earliest wall paintings in the Church of Aghios Nikolaos in Kastellorizo, outside the castle, depicting full-length saints and the Prophet David, date to this era.

Also flourishing economically, Rhodes engaged in lucrative trade with Anatolian ports. Western goods shipped to Asia Minor included woolen textiles and hides; among Anatolian exports were carpets, silk textiles, wheat and ceramics. Serving as a useful gateway to Asia Minor, Kastellorizo, like Rhodes, probably handled a rich variety of trade items that also included perfumes, saffron, wax, pepper, caviar, oil, wine and sugar. To protect its sea lanes and trade, Rhodes dispatched a squadron of three cannon-bearing galleys.

Fending Off Muslim Invaders

With Rhodes’ rising prosperity came increasing pressure from envious competitors, particularly Egyptian Mamluks and Ottoman Turks.

Kastellorizo lay on the front lines, suffering severe destruction and hardship following Mamluk raids in 1440 and 1444. Maltese archives reveal that Rhodians from Lindos assisted the Knights in defending Kastellorizo, called up by the Grand Master Jean de Lastic, who later described the Kastellorizians’ determined resistance as a “heroic achievement.”

Afterward, the island was taken over by King Alfonso V of Aragon, who ordered the port’s damaged castle to be rebuilt (1450) and the island used as a naval base for suppressing Ottoman aggression.

Despite ongoing tensions, regional commerce remained largely unhindered. Following a trade agreement between the Knights and Mehmet II the Conqueror (1451), the Aragonese fleet stationed in Kastellorizo was directed not to deter Turkish shipping from moving freely in Rhodian waters.

Territorial disputes and seaborne dangers never long subsided, as Kastellorizo was soon seized by the Catalans (1461) and the kingdom of Naples (1470). By 1480, the island was largely deserted, due to Turkish and Egyptian attacks. It then came again under the control of Naples (1498), and later the Spanish (1512), before finally being seized in 1523, with the rest of the Dodecanese, by the Ottomans’ Suleiman the Magnificent.

Atrocities On All Sides

Although medieval Christian chroniclers often emphasize the ruthlessness of invading Turks, it seems Westerners, too, mistreated the inhabitants of the Greek islands.

Kastellorizo provided some refuge for Christians during the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War (1570-73), but the later Cretan War (1645-69) proved disastrous. Although a combined French-Venetian naval force succeeded in taking over Kastellorizo in 1659, they could not retain their prize. Departing, they demolished the port’s fortifications and left the island in misery.

The Cretan poet/historian Marinos Tzanes Bunialis (ca. 1620-1685) wrote of the Venetians’ behavior in abandoning Patmos and Kastellorizo: “They took the Greeks captive, behaving as Turks do, throwing them in chains and stealing all their possessions; any men who survived were enslaved and sent straightaway to the rowing benches. They tore down the walls and seized the people, tying up girls and dragging everyone away; even small Christian children and respected women; dragging them all away like deposed politicians and condemned prisoners.”

Return to Prosperity

The 18th century proved a period of gradual recovery, far-reaching commerce and eventual decline. With the Ottomans having consolidated their hold on Kastellorizo, a lasting stability allowed the island’s residents to reestablish their customs, regain prosperity and build anew.

Wood for merchant ships was readily available on the opposite Anatolian mainland, and the port of Mandraki again became a center of shipbuilding and repair. Kastellorizian captains sailed throughout the Aegean, as well as to Constantinople and the ports of Alexandria, Cyprus, Antalya and Tunis. They traded in timber, charcoal, sponges, carpets and a host of other items. Men worked in all aspects of maritime commerce, while women, who often saw their husbands only during winter months, remained on the island managing family properties, running households and raising and educating their children.

Richard Pococke visited Kastellorizo in 1739, noting that the island’s slopes were covered with vineyards and its shores were a haven for Christian corsairs from Malta. Kastellorizians also established small communities on the Anatolian coast (e.g., Kalamaki, Antiphellos, Tristomi, Kakava, Myra, Livisi and Finikas), where they operated second farmsteads producing wine, wheat and other agricultural goods to supplement their incomes.

Greek culture, language and religion also flourished. New churches and monasteries were founded, including the Monastery of Aghios Georgios tou Vounou and the Monastery of Profitis Ilias (1763).

Beside Mandraki harbor, an Ottoman mosque was also built, apparently above an earlier Christian chapel dedicated to Aghia Paraskevi. Its presence attests to a small Muslim community, whose members seem to have peacefully coexisted with their Greek neighbors. The mosque was converted into Kastellorizo’s archaeological museum in 1966, later becoming its ethnographic museum in 1995.

Economic decline toward the end of the 18th century resulted in dire conditions on the island. The Knights’ castle suffered further destruction in 1788, when the infamous Greek pirate Lambros Katsonis and his corsair fleet bombarded the island’s Turkish garrison with cannon fire, then landed and besieged their stronghold. Facing defeat, the Turks surrendered in exchange for safe passage to the mainland. Katsonis hauled away the Ottoman cannons and other loot, but sailed away leaving the Kastellorizians to carry on under Turkish rule.

The Egyptologist Claude Étienne Savary describes the island in 1797 as a “rock,” where the inhabitants “can neither sow nor reap. There are no cabbages, no fruit, no cereals. Just a few olives. From animals, only a few goats climbing the cliffs to find some food … [while] the best house is rented twelve francs a year and the girl who gets a goat and an olive tree for a dowry is considered rich.”

Nevertheless, prior to the 1821 outbreak of the Greek Revolution, Kastellorizo was also credited with having a diverse fleet of large and small sailing ships, the sixth-largest collection of privately owned vessels in the Aegean area, many of which carried cannons. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), Kastellorizian captains ventured far from home to secure large profits, running Britain’s maritime blockade of France to supply food and materiel to England’s enemies.

If the crews of these “outlaw” vessels were caught by the Royal Navy, they were sent to prison in Australia – thus establishing an unintended cultural foothold on that continent which, in later, more troubled times, attracted subsequent generations of Kastellorizians seeking better lives.

© Ecole Biblique et Archaeologique Francaise de Jerusalen

Struggle for Nationhood

Being something of a minor sea power, Kastellorizo was ideally positioned to contribute to the Greeks’ revolutionary war effort against the Ottoman Empire. First sending their families off to Karpathos, Kasos and Amorgos for greater safety, Kastellorizo’s ship owners and other fighting-age men threw themselves straight into the fray, often using their own craft as fire ships to destroy opposing Turkish vessels and chasing the enemy across the sea.

In one celebrated incident, recalled by historian Athena Tarsouli (1950), two Kastellorizian ships captained by Giannis Diamantaras and Hatzi-Stathis Zimpillas, along with a third local vessel, waylaid two large Ottoman ships in the Gulf of Antalya in June of 1821. One of the enemy vessels belonged to the Pasha Muhammad Ali, Ottoman ruler of Egypt; the other carried Muslim pilgrims returning from the Hadj.

During a fierce battle – in which the Greeks’ gunpowder ran out and fighting was reduced to ferocious hand-to-hand combat using swords, lengths of wood and other makeshift weapons – the Pasha’s captain, sensing defeat, tried to blow up his own ship by igniting a powder keg. He succeeded only in destroying the vessel’s superstructure and blowing everyone on deck into the sea, including himself; he was subsequently caught and killed. The Turks suffered many casualties.

In the aftermath, the Pasha’s ship was discovered to hold a wealth of wheat, weapons, gunpowder, luxurious Eastern fabrics and chests of gold and silver coins. All these riches were carried back to Kastellorizo, where great arguments erupted among the populace over the proper division of the spoils.

© Shutterstock

From Greatest Heights…

The people of Kastellorizo, following the Greek Revolution, woke to a cold reality. Although the national struggle had produced a modern Greek State, the Dodecanese islands remained under Ottoman control. Post-war calm and stability nevertheless energized the Kastellorizians, who again rebuilt, pursued new maritime enterprises and revitalized their society.

British archaeologist Charles Fellows expressed awe in 1841 over the island’s newfound sophistication, teeming cafés and waterfronts, bustling shipyards and endless construction projects. “Our impression was that we were visiting another country…. We were told only five Turks live on the island. Small ships and large sailboats filled the harbor…. Everyone in Kastellorizo is very active and seems full of commercial spirit.”

The trade in ancient antiquities was also booming, as the islanders dealt in coins and other archaeological “treasures” they had either unearthed themselves or purchased from other clandestine diggers on the shores of Asia Minor. Some passing captains in the 18th and 19th centuries were said to cash in on Kastellorizo’s rich heritage by directing their crews to seek out ancient tombs whose contents could be plundered and sold.

In 1835, the Kastellorizians welcomed new privileges granted by the Sultan Mahmud II, including self-government, a limited tax burden, exemption from military recruitment and freedom of movement. Ship owners were the leading citizens, while their fellow Kastellorizians comprised sailors, fishermen, sponge divers, shipbuilders, carpenters, shopkeepers, small traders and manual laborers. Women managed domestic life and education was taken very seriously.

By the early 20th century, the island boasted three public schools for boys and girls, with six teachers; three private schools; and a seminary. People lived well, many in luxurious, multi-level neoclassical houses in the packed Kavos district. The Horafia neighborhood beside Mandraki also thrived.

The island’s population reached some 12,000 people and another surge in church-building occurred, including chapels of the Panaghia and Aghios Stefanos at Paliokastro; Aghia Triada on the hill of Profitis Ilias; Aghios Dimitrios tou Kastrou, Aghios Georgios Pigadis and Aghios Merkourios near the port; and those of the Panaghia, of Aghios Spyridon and of Aghios Konstantinos and Aghia Eleni in Horafia. Ten ancient granite columns supporting this last church’s interior were brought over for its construction in 1835 from the Temple of Apollo at Patara on the Lycian coast.

Maritime trade constituted the life blood of Kastellorizo’s flowering economy in the 19th century. To promote local shipbuilding, the famous shipwright Nicoletto Karalis was invited to transfer his operations from Chios to Kastellorizo. Subsequently, the Mandraki shipyards, from 1834 to 1887, produced dozens of small coasting craft and fifty or more merchantmen of 100-300 tons, serving ship owners not only in Kastellorizo but also Hydra, Syros, Mykonos, Milos, Chios, Lesvos, Samos and Santorini.

By mid-century, more than 40 Kastellorizian families owned large cargo ships, while the island’s entire fleet of 165 large and small vessels boasted a total cargo capacity of 24,000 tons. Most Kastellorizian men were sailors.

In 1909, a detailed vessel inventory records: 15 large three-masted schooners (barkobestia) of 35-45 metric tons each; about 45 brigs (brikia), equipped with two square-rigged masts, of 4-21 tons; about 35 luggers (bratseres) of 1-3.5 tons; and about 60 small sailing craft (varkes), of “lateen, Hydriote and fishing” type.

© The late Katina Speros

…To the Depths of War

By the early 20th century, Kastellorizo had reached its peak as a maritime metropolis. The age of the sail was drawing to an end, however. The advent of steam ships began to impact the island’s commercial network and age-old role as a convenient port-of-call.

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 brought additional hardship, as Kastellorizians lost many former privileges. Conscription returned; tax exemptions were abolished; religious freedoms were revoked; and trade with the Anatolian mainland was restricted. Consequently, after 1910, many residents departed – bound for Australia, Egypt, Rhodes, Athens and elsewhere – during the first of several waves of emigration.

Kastellorizo also soon became embroiled in the numerous international conflicts. The Italo-Turkish War broke out in 1911, when Italian forces seized the Dodecanese islands and Ottoman territory in Libya. Kastellorizo, however, was again left to the Turks. Italy ultimately agreed to hand back the Dodecanese, per the Treaty of Ouchy (1912), but the almost simultaneous eruption of the First Balkan War gave it an excuse to renege.

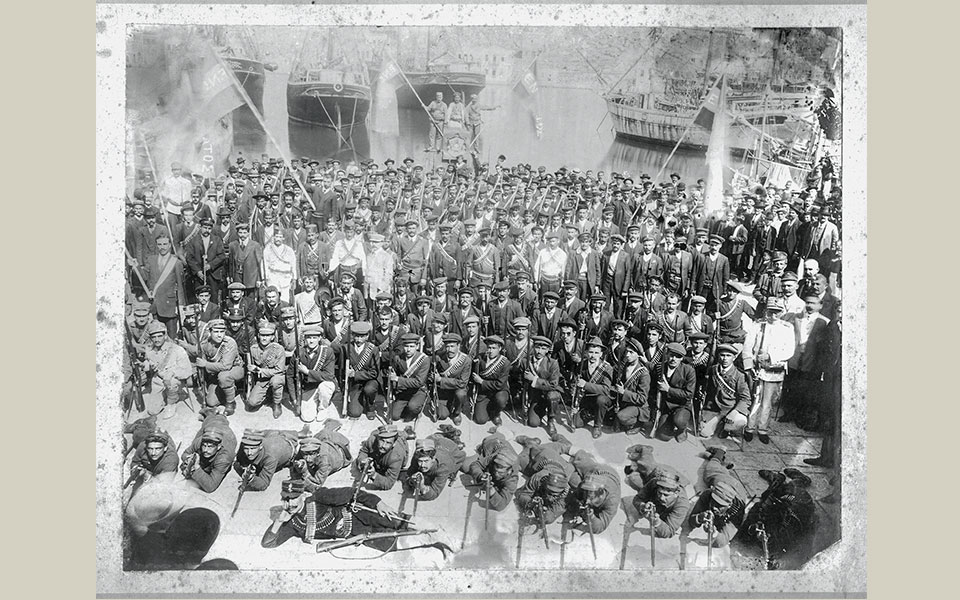

The Turks’ responding naval blockade of the southeast Aegean dealt a severe blow to Kastellorizo, as all commercial activity ceased and more of the island’s economically stricken residents resorted to emigration. The remaining Kastellorizians called for unification with Greece, then openly revolted against the Turks in 1913. They were supported by the Greek diplomat and philosopher Ion Dragoumis, who orchestrated an invasion of thirty Cretan guerrilla fighters and twenty officers from the Samos Gendarmerie.

Together, they took over the island and expelled the Turkish garrison. The Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, however, disagreed with their actions and had to take political and military steps to protect Kastellorizo from a resulting Turkish backlash, which included bloody raids and looting launched from the nearby mainland.

In early 1914, on the eve of WWI, Europe’s Great Powers directed that Kastellorizo again be returned to the Ottomans.

© Nicholas Pappas

New Masters

The inexorable destruction of the Kastellorizians’ once highly developed island and dynamic seafaring society during WWI, the Italian occupation (1921-43) and WWII was, for the islanders, part of a tragic, too-often-repeated pattern. Throughout their history, Kastellorizians found they could not easily be freed from the web of international interests and outside aggression that ensnared them.

In December of 1915, France landed 500 soldiers on the island, aiming to establish a strategic sea base, monitor Germany’s naval movements and ultimately gain a post-war “France du Levant” that would include Kastellorizo, the “pearl of the East.” In response, a Turkish artillery unit commanded by Mustafa Ertuğrul secretly installed on the opposite shore a battery of sixteen guns capable of shelling Kastellorizo.

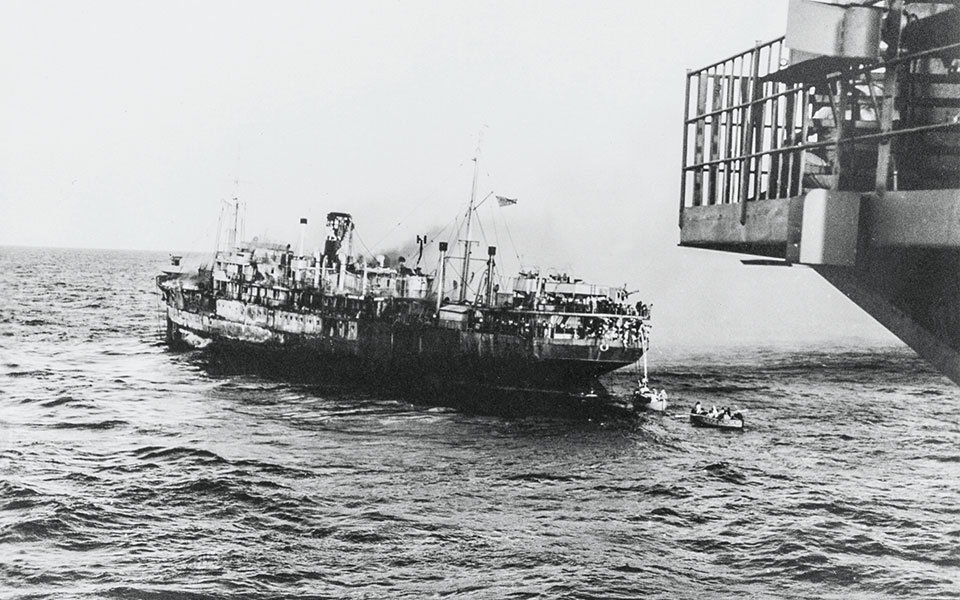

On January 11, 1917, the Turkish guns opened fire on the island after a large British seaplane carrier, the HMS Ben-my-Chree, was spotted entering the port. The French fought back, bravely assisted by Kastellorizo’s citizens, but the surprise Turkish bombardment successfully sank the British ship and destroyed about 1,000 homes. The Ben-my-Chree remained half-submerged in Kastellorizo’s port until 1920, when it was refloated and towed to Piraeus.

Life on the island under French rule was marked by internal tensions between families, continued Turkish attacks, economic suffering and a further exodus of its natives.

Following the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), Italy acquired Kastellorizo from France in early 1921 and created a base for military sea planes. Life for the locals was difficult, as their newly fascist overlords imposed high taxes, restricted basic freedoms and interfered with public education and religious practices. The Kastellorizians felt increasingly isolated, as cross-channel trade relations and access to their mainland properties were also largely severed.

Further calamity struck on March 18, 1926, when a severe earthquake damaged or destroyed 361 houses and devastated the port area, killing two adults and two children. Although Italian authorities mobilized aid from Rhodes and Rome, and the Kastellorizians pulled together in a massive communal effort, recovery was slow. Eventually, new public squares and elegant edifices were constructed, some designed by Italy’s great colonial architect Florestano Di Fausto.

The “Mouzahres”

Kastellorizian resistance to Italian authority, fueled by discontent over stagnating economic conditions and the recent ceding of many of Kastellorizo’s islets to the Turks, came to a violent head in the early 1930s. Tensions among the island’s citizens and leading clans also arose over the shady governance of Ioannis Lakerdis, mayor since 1920, and his followers.

Public frustration was already boiling when a new tax hike was announced on January 12, 1934 – doubling import tariffs on petrol, coffee, sugar and flour. A series of protests, the “Mouzahres,” flared up over the next two months, initially involving all citizens but later predominantly women and girls.

On January 22, Lakerdis was nearly lynched by demonstrators. Three days later, historian Nicholas Pappas writes, “a noisy group of middle-aged and elderly women, many in traditional Kastellorizian dress, gathered outside the council chambers and called for the resignation of Lakerdis.” The next day, twenty carabinieri arrived from Rhodes, and “the women and some youths clamored to the vessel as it docked.” Disembarking, the carabinieri panicked; shoving ensued; warning shots were fired; protestors were struck with rifle butts; some were pushed or fell into the harbor; and twenty women were later reported injured.

A similar disturbance occurred on the first of March, with female demonstrators suffering further injuries and impromptu “baptisms,” while Lakerdis shouted at the crowd, “I will set fire to you all. I will not leave this island without reducing it to ashes!” Finally, on March 25, 1934, after a particularly violent clash, Lakerdis was removed from office, the tariffs were lifted and early elections were announced.

The Mouzahres of Kastellorizo was widely proclaimed a victory for Hellenism, according to Pappas. “Articles appeared in nearly all Greek newspapers heralding Lakerdis’ fall as a moment of triumph for the Greeks of the Dodecanese ‘after centuries of enslavement.’”

With economic hardship unrelenting, however, Kastellorizo’s population continued to decline and, by 1940, emigration had left the island with only about 1,500 residents.

© Imperial War Museum

© Imperial War Museum

Wartime Ravages

World War II brought enormous adversity and loss to Kastellorizo. Already difficult living conditions were compounded by both Axis and Allied military exploitation and maltreatment. A failed British invasion of the island in 1941 was a particularly bitter pill, as the inhabitants were subsequently left to the fury of Mussolini’s brutal fascists.

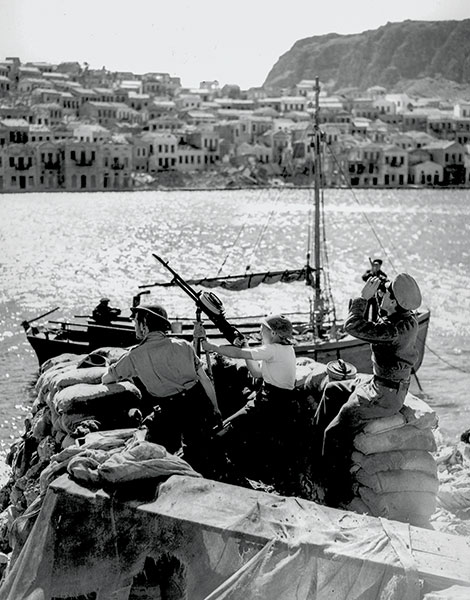

Wishing to quell Italian raids on Aegean sea traffic and to prevent possible future German occupation of the Dodecanese islands, the British decided to establish a base for fast torpedo boats at Kastellorizo. Landing before dawn on February 25, 1941, southeast of the port, more than 200 British commandos quickly overwhelmed the Italian garrison in the castle and the Paliokastro fortress. The Kastellorizians believed liberation was at hand. Celebrations broke out, Greek flags were hoisted and people flooded the streets singing and denouncing fascism.

Sadly, despite naval support, the British had no air support. Italian radio operators sent a plea for help to Rhodes and Italian bombers quickly responded, wreaking havoc on the Royal Navy, Kastellorizo’s port area and the surrounding hills. Over the next two days, Italian troops successfully landed, counter-attacked and forced the British to evacuate on February 28th.

Afterward, already having suffered death, injury and the destruction of their homes, the Kastellorizians were subjected to beatings, executions and imprisonment by Italian authorities for embracing the enemy. To avenge these injustices, a Kastellorizian guerrilla, Nikos Savvas, joined an Allied commando raid that blew up Italian warplanes and damaged two airfields in Rhodes on September 13, 1942.

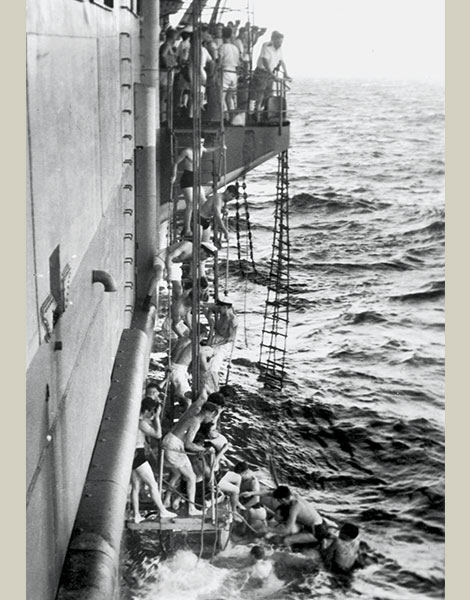

Further misfortune came to Kastellorizo in 1943 when Italy capitulated on September 8th. The British reoccupied the island; it again became a naval base; and the Germans responded with a merciless aerial bombardment lasting from October 17th to November 19th. All remaining Kastellorizians now fled their island.

Some eventually reached Australia, but many others became refugees – traveling through Cyprus or Syria before being settled in large camps in Palestine and Egypt. Firsthand accounts of Kastellorizo’s final exodus in 1943 are eerily reminiscent of similar hardships endured by immigrants entering Greece today, many of them also refugees displaced by war.

Yet more devastation occurred in Kastellorizo in July of 1944, when a British fuel depot exploded. A massive fire engulfed the town, destroying another 1,400 houses. In a final insult, the residents’ abandoned homes were looted of all their valuable possessions. Despite hearing of these calamities, the people of Kastellorizo yearned for their island home.

© Imperial War Museum

An Island Reborn

The Kastellorizians’ return in 1945 was also marked by tragedy, but proved a further testament to their courage and determination to retain their beleaguered culture and restore their homeland to better times.

Under UN auspices, about 1,500 Kastellorizians – mostly women, children and elderly citizens – departed from the Levant in three ships. The first two arrived safely, but the third, SS Empire Patrol, caught fire after leaving Port Said. Thirty-three adults and young children perished. The accident and its victims are still commemorated annually in Kastellorizo, where an inscribed monument also preserves their memory.

In a 2016 BBC interview, Maria Chroni, a lifelong Kastellorizian, described being rescued when she was only eight years old: “I found myself at sea, holding on to a wooden plank…. How it happened, I can’t remember. I only know I that I stayed in this position for ten hours. Then my father rescued me and lifted me into the charred boat.”

After WWII, Kastellorizo remained under Allied control until at last it officially joined Greece on March 7, 1948.

Since then, the island’s fortunes have been steadily improving. Recent international tensions swirling around Kastellorizo highlight its enduring economic and geopolitical significance.

The efforts of Kastellorizians both on the island and around the world are bringing ever greater respect for its unique turbulent history and the resilience of its people.