On Kefalonia, Winemakers Adapt to Rising Temperatures

Climate change brings water scarcity and...

Stavroula Kourakou-Dragona continues to write, sharing her wisdom on wine.

© Dimitris Michalakis

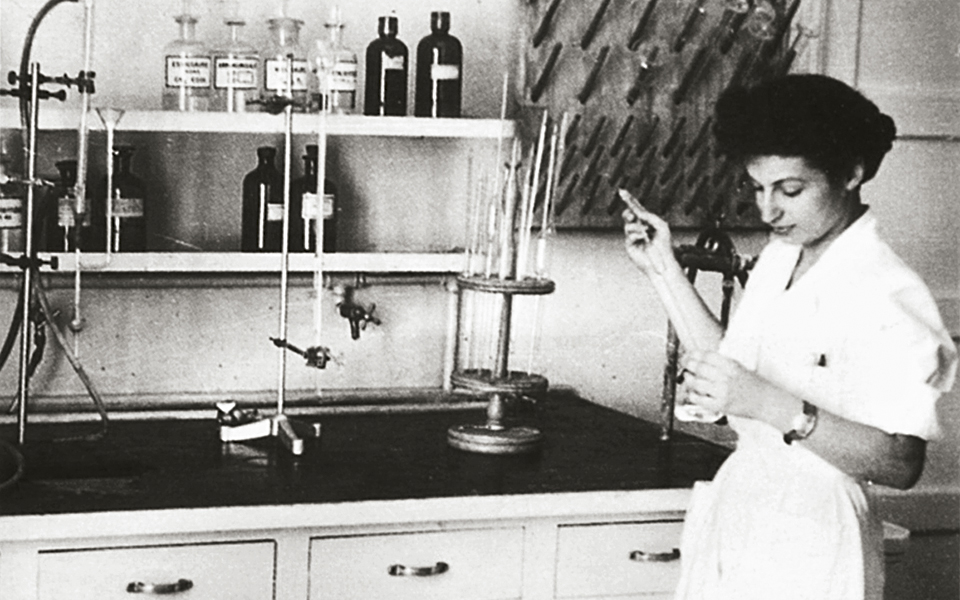

A few hours in her company is the ultimate crash course in the revival of the Greek vineyard, that has been her life’s work. More than 60 years have elapsed since she found herself – doctor’s degree in chemistry in hand – working at the Ministry of Agriculture’s Wine Institute: “I was a city child who knew nothing about the countryside nor had ever seen a vine or tasted wine.”

And what was there to taste? Devastated by phylloxera and war, the Greek vineyard was scorched earth; its product discredited, producers left to the mercy of God and bulk merchants, the legislation outdated. Stavroula Kourakou-Dragona threw herself into the battle with all guns blazing. With her scientific background, vision and determination, she took on the narrow-minded establishment and defended Greek interests at European agencies. During her extensive study of the country’s wine regions, she traveled by jeep and mule, spoke to growers in the field or later at the kafenio. She tasted wines from indigenous varieties and recorded the primitive production methods. She mapped the entire winegrape-growing landscape both before and after World War II. This city kid came to love the rural world. She had experienced its troubles up close and broken bread at its humble table. The chemist realized that the secret to good Greek wine was not to be found only in the wineries and the technology they applied, but at the source, the vineyards. It is to Kourakou-Dragona that Greece owes the system for classifying its vineyards, its updated legislation and the classification of most of its 33 appellations of origin, the most recent being Vinsanto and Greek Malvasias. Without her, it is unlikely we would be speaking of a new era in Greek wine today, and her contribution has been internationally recognized. She was unanimously elected president of the intergovernmental International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), has been decorated by France, Spain and Italy, was recently awarded by the Academy of Athens and has written dozens of articles and 15 books that have been translated into several languages. The most recent, are Vine and Wine in the Ancient Greek World (2014), which was awarded by the OIV, and Santorini: An Historical Wineland (2015, both Foinikas Publications).

“The product of our small and scattered vineyards will never flood the markets. It is intended, instead, to break the boredom of the monotony of aromas and flavors from the immoderate prevalence of globalized cultivars.”

Where it all began: As a young chemist at the Wine Institute’s laboratory, in 1953.

© Dimitris Michalakis

Now aged 88, Kourakou-Dragona is still standing on the ramparts, watching Greek wines earn international distinctions and her vision being vindicated. Of all the titles and honors bestowed on her, she still holds dearest that of “Lady of the Vines”, inspired by the poem of the same title by Yiannis Ritsos, which was how she was presented to the readers of Kathimerini newspaper by editor-in-chief Kyriakos Korovilas at a time when she was representing Greece and addressing its wine economics at decision-making centers in Paris, Brussels and Strasbourg. “I simply feel like a person who deserves to live, who hasn’t led a wasted life,” she once said. “I was fortunate and happy to see the birth in this country, from scratch, of an entire field of research, application, science, industry, commerce and international relations. If I could be born again, I would wish to live the same life all over again – even its difficult times. This full life, which was dedicated to the service of the wine sector.”

How would you introduce winemaking Greece to a foreign visitor?

In 1978, Greece hosted the OIV general assembly. It was our duty as host to present samples of our production, but back then we had few Greek wines to showcase that were on the market and of some notable quality, with the exception of the internationally renowned sweet wines of Samos. So, I organized a huge tasting for 200 experts with 40 samples that had been produced at the Wine Institute’s experimental winery. As the waiters filled glasses, I projected images on a big screen of the grapes of every variety and its name, as well as vineyard landscapes from the areas where they were cultivated. Our foreign guests got to know about the terrain of the country and cultivation in terraced vineyards that in some parts start at sea level and reach altitudes of 800 meters; they saw small balcony vineyards overlooking the Aegean and learned about the islands’ volcanic soils – and it is a well-known fact that winegrapes love volcanic earth. They were impressed by how the vines in Santorini are shaped into baskets to protect the grapes from strong winds. Moreover, they were amazed at the wealth of the varieties being grown in this small country and at the differences in organoleptic characteristics in different wines from the same variety when grown at different altitudes and/or in different terroirs. As time passed, I repeated this process of “initiation” with various groups of foreign visitors until a number of splendid wine-growing holdings were established and bottled wines from native grape varieties appeared on the market. It was no longer necessary to resort to experimental samples. I would use this same method today to introduce people to the world of Greek wines.

“Of all the titles and honors bestowed on her, she still holds dearest that of “Lady of the Vines”, inspired by the poem of the same title by Yiannis Ritsos.”

On Santorini, the subject of Kourakou-Dragona’s latest book, entire hillsides have been arranged in stepped terraces to protect the soil from wind erosion (courtesy of Foinikas Publications).

Some argue that Greece’s native varieties are difficult to pronounce and that this harms their commercial appeal. What’s your view?

Consumers don’t have a problem pronouncing the German cultivar Gewurztraminer. Is that easier to say than Xinomavro? Or are Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon easily or correctly pronounced by non-French speakers? I find that our varieties – Robola, Vilana, Assyrtiko, Debina, Mavrodafni, Limnio, etc – are much more manageable for foreigners. I accept the comment only for Agiorgitiko. But this variety is cultivated in the Nemea zone – a short toponym, which, written in capitals, is easy to read in all the Romance and Anglo-Saxon languages. So why shouldn’t Nemea be written on labels as the main indicator and Agiorgitiko as the secondary one? Foreign consumers would soon be familiarized with the notion of toponym first, variety second. This could also be the case for other Greek areas, for example: Santorini/Assyrtiko, Naoussa/Xinomavro, Crete/Kotsifali, Rhodes/Athiri, etc. All of these places are also known as tourism destinations. This is how to promote wine tourism. After all, the names of the grape varieties are not protected. In the future, a bar in Santorini may sell a cheap Assyrtiko wine from, say, China or Chile. Greek winemakers need to understand this: all they own is geographical designation; only the name of the wine’s geographical origin is protected. It’s a big mistake to display the variety on labels without linking it to the location where it is cultivated, particularly when the area is known for its archaeological sites, like Nemea, Santorini, Crete, Rhodes etc.

In what state was the Greek wine sector when you started your career?

Wines from all parts of the Mediterranean, not just Greece, had been considered inferior since the start of the 20th century. They were regarded as a cheap raw material for northern European distillers and vinegar-makers, at best suitable for blends in wines from unripe grapes in order to raise their alcohol content and/or enhance their red color. Naturally, the bulk export market used grapes from low-lying vineyards that cultivated just two or three varieties yielding high-alcohol wines, which is what importers were looking for. And then World War II happened and Greek vineyards continued to decline as the countryside was depopulated. High-altitude, mid-altitude and island vineyards, those that had the greatest potential, were abandoned. Prime winegrapes were lost. When I was appointed to the Wine Institute in 1953, the sector was still in the preindustrial age and Greece, devastated by war, was struggling to heal its wounds.

“Greek winemakers need to understand that all they own is geographical designation; it’s a big mistake to display the variety on labels without linking it to the location where it is cultivated.”

Stavroula Kourakou-Dragona, president of the OIV, at a reception in Vienna City Hall during the 1980 assembly.

Sitting on a VIP throne in the Theater of Dionysus in Athens, 1964.

Mexico City, 1981. Presiding over the OIV assembly.

When did the fortunes of Greek wine begin to change?

I would say 1970, when the Ministry of Agriculture classified by law the grape varieties by area according to their quality score, as this emerged from the research of the Wine Institute. Economic incentives were also introduced for the expansion of prime winegrapes in areas with the appropriate soil and climatic conditions, and so vineyards were resurrected when and where the demographic factor allowed their revival. It was then that modern technology was applied in wineries. Marketing also made its first appearance in the Greek wine sector and European regulations dictated a common policy for wine labeling. Appellations of Origin of High Quality (AOHQ) were first granted to Greek labels in 1971.

Was this also the time when the old guard of the winemaking world passed on the baton to the younger generation?

Yes. And most of these young people had studied viticulture and viniculture abroad. Meanwhile, the sector’s representation at EEC conferences and committees helped advance the right policies on issues pertaining to production, evaluation and the commercial promotion of Greek wines. Additionally, the significant investments in human resources and technical capabilities sensationally improved the quality of the wines, at least on the processing level. This impressive improvement of Greek bottled wines is obviously due to a number of factors, which came together by serendipity and augmented one another, just as co-linear forces are added to give a resultant force far greater than its components. The fact that a recovery was achieved in such a short period of time is proof of the dynamism of the winemaking sector.

Old vertical hand-operated grape press. From her book Santorini: An Historical Wineland (Foinikas Publications).

The best way to enjoy Αgiorgitiko. From her book Nemea: An Historical Wineland (Foinikas Publications).

What are Greece’s advantages on the global wine map?

The wealth of its native winegrapes, in combination with the particular characteristics of its ecosystem, to which each variety adapted centuries ago. Quality and uniqueness, not quantity, are our biggest strengths. The product of our small and scattered vineyards will never flood the markets. It is intended, instead, to break the boredom of the monotony of aromas and flavors from the immoderate prevalence of some, few globalized cultivars.

Greece also cultivates foreign varieties…

That began in the 1970s. Still, the area they cover represents only 10 percent of our vineyards.

Does the Greek vineyard have more “hidden treasures” to reveal?

Today we have 90 winegrapes being vinified that are unique in the world, but we still have a lot of areas that have not been developed (on mountains and islands), which were renowned in centuries past for their wines. It is thought that these areas may still have grape rootstocks, with a lot of surprises in store. The explosion in quality, however, is expected to come from the already cultivated varieties, once the cloning selection programs are completed, as well as the cultivation of plants that are immune to viruses.

Where would a pioneer such as yourself begin today?

We have accomplished so much in such a short space of time, yet we all feel that the quality of native varieties is not high enough to establish Greece firmly on the international map as a wine-producing country. We need collective initiatives. One swallow does not make a spring. And this, thankfully, is something our producers are well aware of.

APPELATIONS OF ORIGIN OF HIGH QUALITY (AOHQ)

Some wines in international commerce are known by the geographical names that state their origins. They all come from viticultural zones that are delineated by law, within the specific geographical boundaries of the named areas, and have come to be known as “Apellations of Origin.” They are produced according to specific terms defined for each individual apellation by that country’s laws. Therefore, the legal term AOHQ is in fact a geographical name: Samos, Nemea, Naoussa, Santorini, etc.

PROTECTED DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN (PDO)

This indication replaced AOHQ as an outcome of bringing greek wine legislation in line with EU. The two indications are equivalent. The characters of these wines express the terroir they come from. The winemaker does not have the right to alter the type of wine according to market demand.

PROTECTED GEOGRAPHICAL INIDICATION (PGI)

Wines in the PGI category enjoy more freedom when it comes to varietal composition and processing and, as such, the type of wine expresses processing choices intended for specific markets. These wines do not express the terroir as much as the winemaker’s technical abilities.

Climate change brings water scarcity and...

Since 1928, this family-run wine taverna...

Why not try a brief getaway...

The Thessaloniki-born winemaker welcomes us to...