The 4-meter-long frieze from the wall of room 5 in the West house at Akrotiri of Santorini, depicting a flotilla is very impressive. Military sailboats appear in two rows. The helmsman stands in front of the small captain’s cockpit. In the bottom row, the ships’ sails are lowered. Also visible are the helmets and spears of the warriors, and the heads and hands of the oarsmen, bent over the oars. The guards and watchmen crowd around the port, while the local residents are rushing out of their multi-story houses and down to the wharf to welcome their loved ones. It looks like a colorful storybook.

It is one of many wall paintings recovered at the archaeological site of Akrotiri in Santorini and restored, but which are not on display in any museum. And by all indications, it will be many years before that happens. However, they can be viewed in the exciting new publication, Prehistoric Thera, released by the John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation, with texts written archaeologist Christos Doumas, head of the Akrotiri excavations. The book is not a commercial undertaking. It is being distributed free to research bodies, museums, and university libraries both in Greece and abroad. It is freely accessible to the public as an e-book.

© Vangelis Zavos

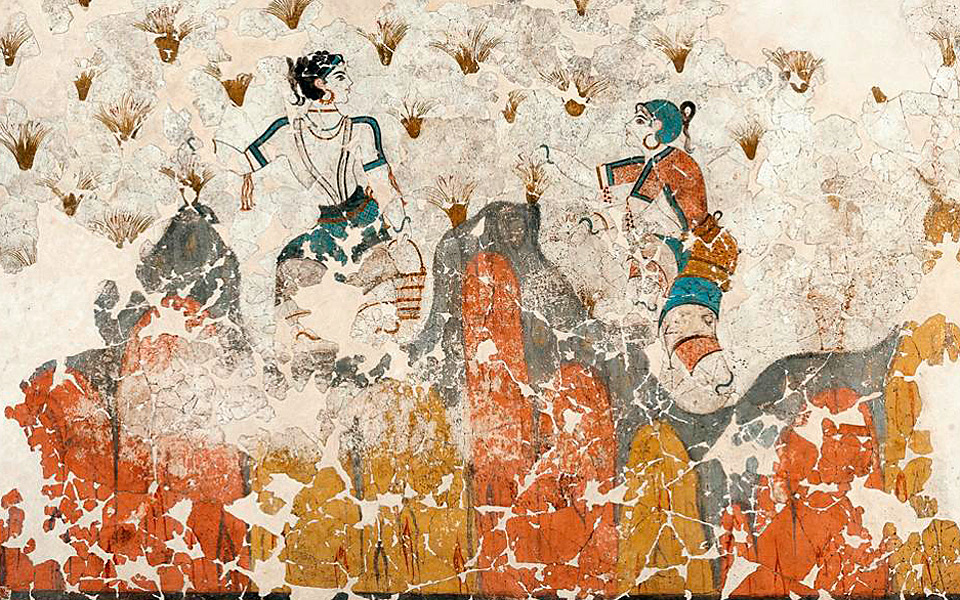

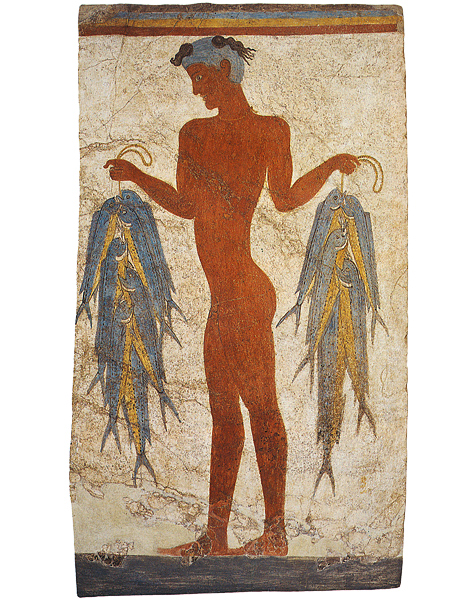

This edition offers a plethora of information on the island society of the Cyclades, which 4,000 years ago created this urban center in the prehistoric Aegean Sea. It features impressive, privately owned and public multi-story buildings, wall decorations of unmatched beauty, illustrated ceramic vessels, illustrations of a variety of subjects drawn on jars, and traces of furniture in houses that was preserved in lava. Images of dolphins swimming in the sea, male figures making ritual offerings, high priests, and items such as skyphos wine cups, rhyta drinking vessels and bottles – all designed with inexhaustible imagination – fill the 323 pages of the book. The texts and images provide insight into the customs of the inhabitants, the way they dressed, how they wore their hair and what they ate.

Details account for the establishment of the settlement as a Neolithic village in the early urban center (3rd millennium BC), the mid-Cycladic city (2000-1650 BC) and Akrotiri at its peak (ca. 1650-1615 BC). It also includes the story behind the Museum of Prehistoric Thera.

© National Archaeological Museum, Athens

© Museum of Prehistoric Thera

There is the “Μuseum of images,” as the archaeologist describes Part III of the book. It is a virtual museum of prehistoric Thera that helps readers form a clearer picture, rather than being limited to the artifacts at physical museums.

The wall paintings are in a class of findings that have not received the attention they deserve, according to Doumas. In the space of half a century, since excavations began, “only half of the wall paintings uncovered by Marinatos until 1974 have been conserved and restored.”

Culture Minister Lydia Koniordou said at the book presentation that the “beleaguered spirit of the times can draw inspiration from antiquity,” while Vangelis Chronis, member of the John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation executive board noted that, aside from its charitable work, “culture cannot be absent” from the Foundation’s activities. In the forward of the book, Marianna Latsis cites “the stentorious beauty of its volcanic landscape.”

What does the reader stand to gain? After 50 years, it is finally possible to see an outline of the history of the prehistoric settlement and its gradual development, and to form an image about the progress of the society that lived in what Doumas describes as “the Pompeii of the prehistoric Aegean.”

The publication is the 18th in “The Museums Cycle” series and bears the stamp of Olkos Publishers.