The Best Ancient Sites to Visit this Fall...

Step beyond Athens this autumn and...

The archaeological site of Ancient Olympia

© Mythical Peloponnese

Olympia, home to the ancient Olympic Games and one of Greece’s most revered archaeological sites, stands in the western Peloponnese as a compelling reminder of past achievement, diplomacy and religious devotion. Nowadays, our understanding of the life and rituals that once thrived at Olympia is changing. In contrast to an often idealistic view of ancient Greek sport, a more balanced perspective is emerging that draws our attention to the telling evidence of Olympia’s own richly preserved ruins and colorful history.

Since the launch of the modern Olympics more than a century ago, the athletes of ancient Olympia have frequently been characterized as amateurs, competing in an international, conflict-free, uncommercialized environment, admirably pursuing athletic excellence in accordance with the values of piety, endurance and humility.

A fuller, more accurate picture – advanced by revisionist scholars such as Donald Kyle, Alfred Mallwitz and Catherine Morgan – instead emphasizes the local, religious and austere nature of the early Olympic games; the occasional military and political intrusions; the ubiquitousness of peddlers and other profit-seekers; and the professionalism of the often highly-trained competitors, whose primary interest was winning, to gain prizes and other rewards. Also notable is the surprising brutality and potential deadliness of some events; the erotic appeal of the athletes; and the readiness of participants to embrace cheating and corruption – against which the judges (Hellanodikai) had always to be on their guard.

“ Since the launch of the modern Olympics more than a century ago, the athletes of ancient Olympia have frequently been characterized as amateurs, competing in an international, conflict-free, uncommercialized environment. ”

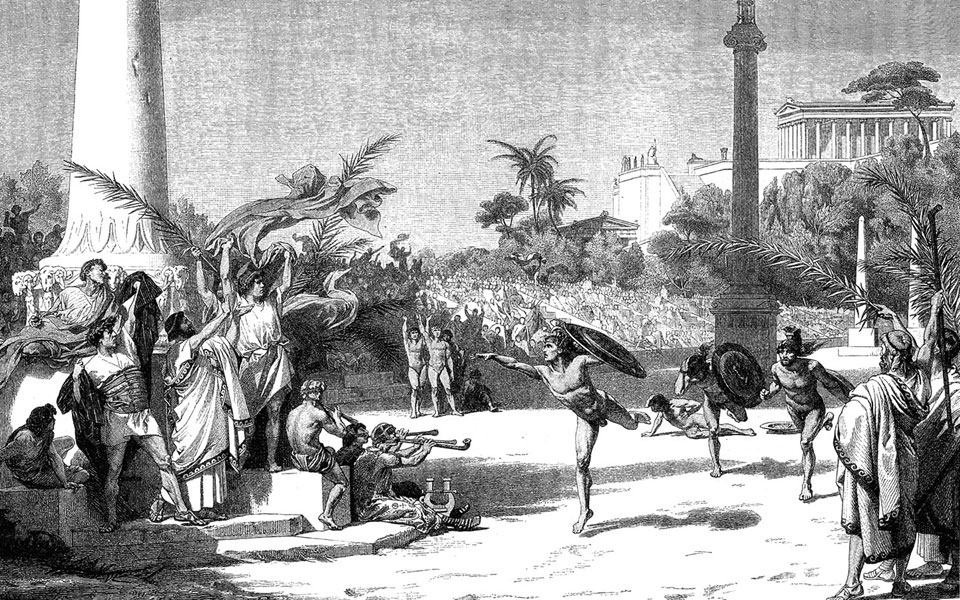

An artistic representation of the ancient Olympic Games, in Hellas: The Life of the Ancient Greeks (1887), by Jacob von Falke (Source: Aikaterini Laskaridou Foundation – Travelogues).

“ Through the Classical era, the sanctuary’s focus remained the worship of Zeus, with only the simplest measures taken to provide for athletes and spectators. Gradually, however, the emphasis changed and the games became more elaborate and important, as reflected in the site’s architectural development. ”

This fascinating dark side of the ancient Olympics includes a particularly notorious case of imperial rule-bending and self-glorification. After the Roman Emperor Nero managed to change the schedules of the major games at Olympia, Isthmia, Nemea and Delphi in AD 67, he “competed” in all four Panhellenic festivals and was awarded a total of 1,808 victory crowns! His list of events included lyre-playing, singing, acting, oratory and four-horse chariot-racing – in which he himself used 10 horses. Later, Olympia’s officials declared the games invalid – but only after the infamously murderous emperor had removed himself to the Underworld.

Sanctuaries in ancient Greece, exemplified by Olympia, were clearly defined precincts dedicated to one or more gods, within which one would find altars, temples and small shrines, as well as a typical array of associated buildings that accommodated the needs of pilgrims, athletes and other visitors.

The heart of Olympia’s sanctuary was the Altis: the central, sacred area containing the now lost Altar of Zeus; the Doric temples of Zeus, (ca. 470-457 BC), Hera (ca. 600 BC) and Cybele or Rhea (Metroon, early 4th century BC); and the Precinct of Pelops (Mycenaean, renovated in the early 5th century BC). The formal sanctuary was established during the 10th-8th centuries BC, while the earliest games are traditionally dated to 776 BC. Large-scale competitions did not appear until about a century later. Through the Classical era, the sanctuary’s focus remained the worship of Zeus, with only the simplest measures taken to provide for athletes and spectators. Gradually, however, the emphasis changed and the games became more elaborate and important, as reflected in the site’s architectural development.

The lighting of the Olympic torch before the modern games by the High Priestess. The ceremony takes place in the temple of Hera at Ancient Olympia, opposite the Temple of Zeus.

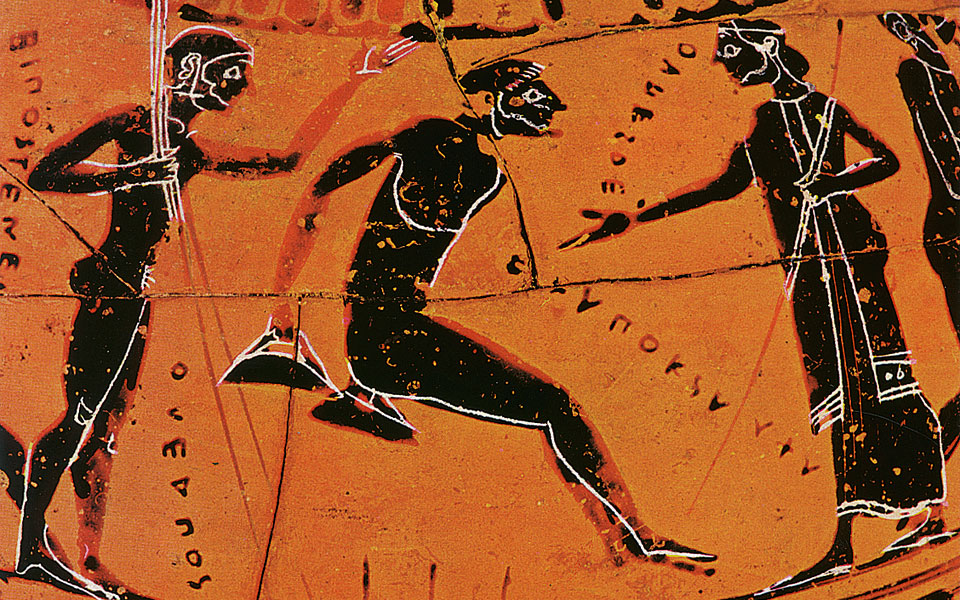

Detail of a black-figure amphora, depicting a long-jumper at the moment he releases his jumping weights (halteres) and lands in the pit (British Museum, London).

By Hellenistic and Roman times, the sanctuary and its surrounding area featured a gymnasium, palaestra, stadium, hippodrome and leschai – athletes’ clubhouses. Visitors’ accommodations included hostels, baths, stoas (colonnades) offering protection from the weather, and ceremonial dining halls, the grandest of which was the Leonidaion with 80 rooms and a central peristyle courtyard. Official buildings included the Bouleuterion (council/court house), where judges and athletes swore to participate fairly in accordance with the rules. The “Zanes” statues, however, paid for by dishonest athletes and placed outside the stadium’s entrance, indicate that not all competitors adhered to their vows.

Of special note are the buildings that recall the far-reaching cultural and political significance of Olympia. On a terrace overlooking the Altis was a row of small treasuries, erected by city-states from all around the ancient Greek world to house precious dedications. Just beside them was a tall, statue-adorned nymphaeum (fountain house), donated by Athens’ Herodes Atticus or his wife Regilla (mid-2nd century AD), which provided a welcome source of water. Further west, Philip II constructed a circular Ionic/Corinthian heroon (after 338 BC), which showcased the Macedonian royal family and his own newfound dominance over Greece. Outside the Altis, Pheidias’ workshop offers tangible evidence of the sculptor’s industrious efforts at Olympia, where he produced a gigantic, chryselephantine cult statue of Zeus (ca. 430 BC) that presided over the sanctuary for some 800 years and became one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Events at the ancient Olympic Games consisted mainly of foot races (some in full armor), equestrian contests, the pentathlon (discus, javelin, long jump, foot race, wrestling), boxing and the pankration – the last two of which could leave competitors severely disfigured or even dead. No boxing gloves were worn, while the pankration’s rules barred only biting and eye-gouging.

“ The ‘Zanes’ statues paid for by dishonest athletes and placed outside the stadium’s entrance, indicate that not all competitors adhered to their vows. ”

The Philippeion, initially built by Philip II, king of Macedonia, after his victory at Cheroneia (338 BC), and completed by his son Alexander.

© Shutterstock

Olympia’s museums should also not be missed. The Museum of the History of the Ancient Olympic Games contains statues, painted vases, inscriptions and other illuminating artifacts related to ancient athletics. The Archaeological Museum offers many impressive displays, among them the pedimental, Severe Style sculptures (early 5th century BC) from the temple of Zeus. The east pediment depicted a scene from the mythical chariot race between Oenomaus and Pelops, while the west featured centaurs fighting with Lapiths (the Centauromachy). The temple’s metope panels portrayed the labors of Heracles. Other displays include the magnificent Parian-marble Hermes and the Infant Dionysus, produced, or at least inspired, by the 4th-century BC sculptor Praxiteles.

ANCIENT OLYMPIA

Olympia (prefecture of Ilia)

• Tel.: (+30) 26240.225.17

• Opening Hours: Summer 08.00-20.00

(autumn and winter closing times vary).

• Admission: Full: €12, Reduced: €6

(Valid for both Olympia

and the Archaeological Museum)

Step beyond Athens this autumn and...