A Michelin-Star Culinary Journey on the Athenian Riviera

This summer, Pelagos at Four Seasons...

The stone-paved pathways, tree-planting scheme and other interventions in the area surrounding the Acropolis – all works by Dimitris Pikionis – had a major impact. Now aside from being a famous archaeological site, the area also offers pleasant walks in a green environment.

© Giannis Giannelos

Dimitris Pikionis was born in Piraeus, towards the end of the 19th century. Just a few kilometers north of the port city, what has become known as the “Acropolis landscape” was unrecognizable. It was a practically barren, heavily-grazed area that was largely devoid of structures with an abundance of open ground.

The first attempts at reforestation were confined to the western foot of the hill of the Acropolis, mainly on the route linking the Makryianni area with Filopappou Hill – the latter having been completely stripped of any vegetation (that route is the now popular pedestrianized Dionysiou Areopagitou Street).

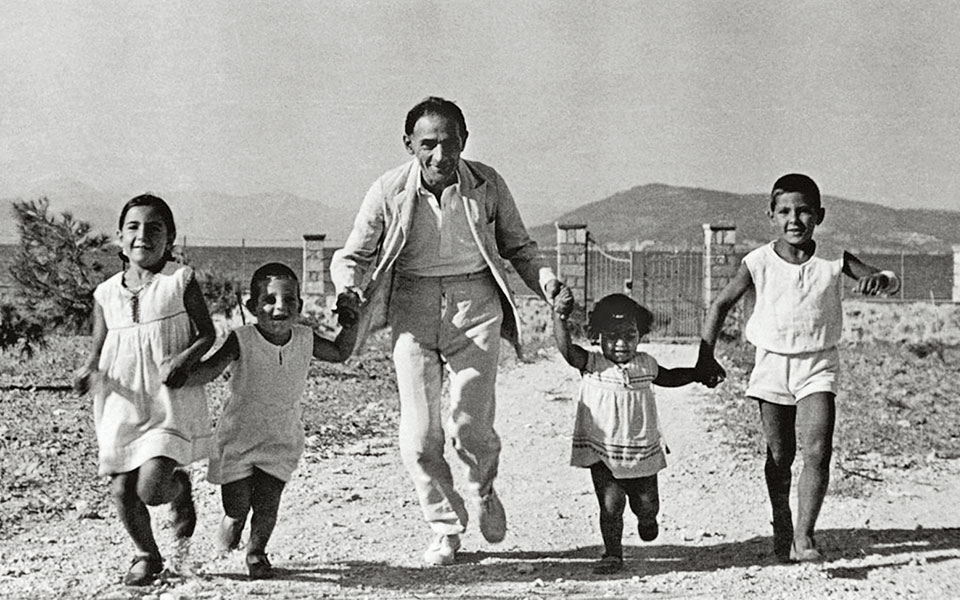

Dimitris Pikionis with his children Ino, Iona, Tasos and Petros on Aegina, around 1937.

© Dimitris Pikionis Archive - Benaki Museum Neohellenic Architecture Archives

The road towards the Acropolis, 1954-1957. Photo by Helen Binet.

© Dimitris Pikionis Archive - Benaki Museum Neohellenic Architecture Archives

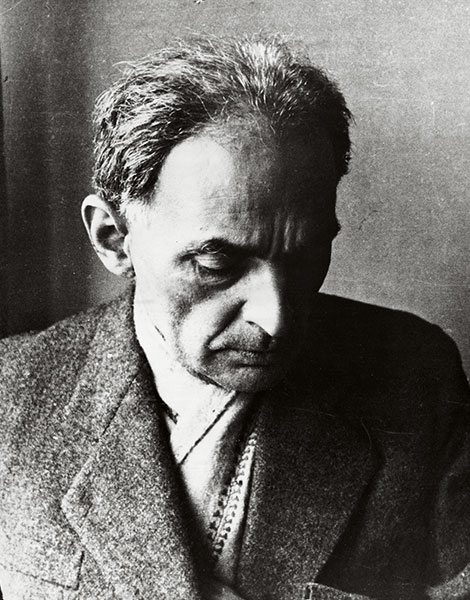

Dimitris Pikionis in a photograph taken by Professor Pavlos Mylonas around 1956.

© Dimitris Pikionis Archive - Benaki Museum Neohellenic Architecture Archives

In contrast, the Acropolis monuments themselves, together with the impressive arches of the Roman Odeon of Herodes Atticus – which had been excavated three decades previously (1857) – did not differ much from what we see today (with the exception of the scaffolding). This is because the geographically limited and penniless Greek kingdom of the 19th century had placed the showcasing and protection of its ancient heritage at the top of its list of priorities, immediately establishing the Archaeological Service in an exemplary fashion.

Thus, by the mid-19th century, Greek archaeologists had already conducted significant and tangible excavations. In doing so, they had also succeeded in gaining the admiration of foreign visitors arriving in the then tiny and dusty Athens with the aim of discovering the celebrated antiquities of the city, free of the corrupting and profane additions of the Ottoman period.

This picture was not at all unfamiliar to Pikionis himself, who wrote in his Autobiographical Notes: “Even when I was a secondary school student, I would often go on treks exploring the Attica landscape. From Moschato, passing through the olive grove, I would reach as far as the rocks of Filopappou and the Acropolis.”

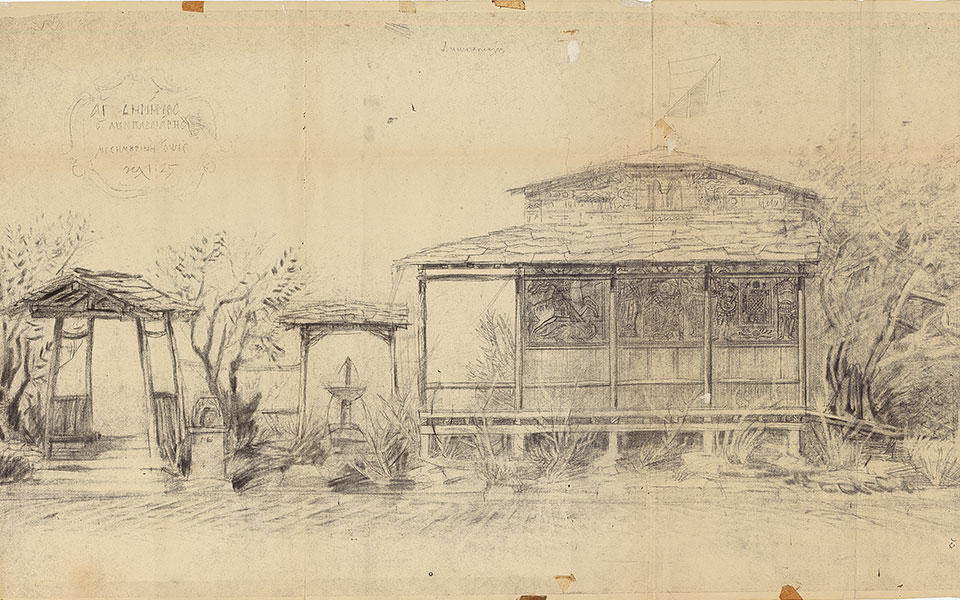

The propylon and the church of Aghios Dimitrios Loumbardiaris in the mid-1950s.

© Dimitris Pikionis Archive - Benaki Museum Neohellenic Architecture Archives

However, the Greece of 1887 bore no relation to that of the early 1950s, when the Minister for Public Works, Konstantinos Karamanlis, entrusted Pikionis – by that time a renowned architect and professor – with the remodeling of the Acropolis area. The country – now much larger geographically, but also wounded in a myriad of ways by the German occupation and an exceptionally painful civil war – was attempting to get back on its feet. At the same time, it was the period when the sirens of a very early version of what we would now call the “tourism industry” were beginning to sing their song in Greece. The combination of unique antiquities, the recreational opportunities offered by the Greek sun and the endless, unpolluted coastline was an advantage that could not be easily ignored.

The choice was clear, and the foundations were laid during those years. It was back then that the Athens Festival was founded, the Odeon at the foot of the Acropolis put to use, and the “Sound and Light” tourist multi-spectacle established. Within this framework, it was not possible for the primitive system of visitor access to and through the Acropolis to remain. The assignment of the project to Pikionis is credited as one of the most brilliant initiatives taken by Karamanlis, who would later serve as prime minister and president.

Aghios Dimitrios Loumbardiaris: south-facing side. A sketch by D. Pikionis.

© Dimitris Pikionis Archive - Benaki Museum Neohellenic Architecture Archives

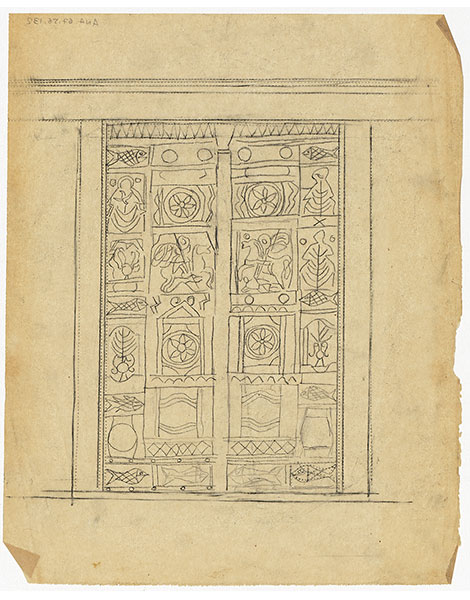

Aghios Dimitrios Loumbardiaris. A sketch by D. Pikionis of the church’s doors.

© Dimitris Pikionis Archive - Benaki Museum Neohellenic Architecture Archives

A detail from the stone-paved road on Filopappou Hill. Photo by Helen Binet.

© Helen Binet

Pikionis’ interventions were much more than a technical arrangement of access routes to the Acropolis monuments and linking them structurally to Filopappou Hill. They imposed a new, almost timeless, reading of the landscape on the area, and this remains their greatest achievement, six decades later (the project wrapped up in February 1957). Traversing the famous flagstone-paved road that branches into two basic directions (the one leading to the Acropolis, the other to Filopappou), with the somewhat forgotten “Pikionis junction” serving as the meeting point, the visitor is unable to pinpoint where the ancient trail begins and ends, as Pikionis’ team ingeniously conceived and created (almost with their bare hands) an extended zone covering some 80,000 square meters.

An architect with a modernist background (the famous school he designed on the slopes of Lycabettus Hill in the 1930s is held to be one of the best examples of Greek modernism), other influences gradually flowed into his work from his wider Hellenocentric reading of things. He quickly attained a completely personal idiom in which the modern was necessarily filtered through the values and traditions of the Greek landscape and Greek life.

Long before Pikionis began to tackle the Acropolis projects, this renaissance figure (who was also a gifted painter) had had the opportunity to deepen his reappraisal of Byzantine tradition, travel to Chios to appreciate the master craftsmen in the land of his grandfathers, re-examine his stance concerning the superficial modernization of his age and value the simplicity of Japanese architecture. In short, he was able to change within himself, to become what we have the fortune of having inherited through his extremely personal view, a view which he transfused unaltered into the most sensitive landscape in the whole of the Greek world.

The café north of the church of Aghios Dimitrios. Originally it was designed as a space for the faithful to gather after mass, rest and enjoy refreshments.

© Yorgos Prinos

However, it was not just that. Might it have been, then, the asymmetrical stone clusters of the flagstone pavement at the Acropolis and Filopappou? The way he conceived the pavilion/rest area next to the single-nave basilica of Aghios Dimitrios Loumbardiaris? The completely manual method (rock by rock) he used during the four years he worked there, assisted by specialized craftsmen from every corner of Greece? His persistence in the strict selection of plants so that they would fulfil the prerequisites and demands of timeless Attic flora? The methodical recycling of older materials (which he himself collected by scouting around Athenian neighborhoods during the time of the mass demolition of neoclassical houses)? Indeed, it was all of the above – and even more – that contributed to the rise to prominence of Pikionis’ architectural ethic, principles which at the same time also served as his passport for recognition abroad. He was both modern and popular, both a person of the world and a localist, both universal and a Greek.

Thus, Pikionis’ topocentric modernism became a point of reference for postwar Greece, as to what “Greek landscape” meant and how it could be managed with respect and inspiration. From a certain point on, Pikionis’ work on the Acropolis represented Greece as the philhellenes of the fragile postwar world chose to see it.

The asymmetrical stone clusters of the flagstone pavement, a trademark of Pikionis’ work.

© Yorgos Prinos

As Kenneth Frampton, one of the most acclaimed architecture critics worldwide, so aptly put it in his prologue to the monumental anthology of Pikionis’ work, published by Basta-Plessa Editions in 1994:

“Somewhere in the sweep of this breaking wave came a point that lay beyond history, wherein the architect arrived at a dematerialized mode of expression that was at once Greek and anti-Greek; Greek in the sense that it was of the place, integrated into the mythos, the landscape, the climate and the way of life; anti-Greek in that much of its inspiration lay elsewhere, remote in space and time, in other far-flung islands, in Honshu and in the archaic pre-Hellenic Aegean under a timeless sun.”

Pikionis himself summed it all up in a single phrase: “It would suffice here for me to say that I am an oriental.”

This summer, Pelagos at Four Seasons...

Whether you’ve just stepped off a...

Discover a vibrant neighborhood where nightlife,...

Echoes from history meet everyday life...