The Best Ancient Sites to Visit this Fall...

Step beyond Athens this autumn and...

The Lion Gate (ca. 1250 BC), the oldest example of monumental sculpture in Europe. Its four massive stones weigh more than 60 tons.

© Mythical Peloponnese

The Cyclopean-walled fortress at Mycenae ranks among the most awe-inspiring places a visitor can experience in the Peloponnese. Especially at times or seasons when few fellow travelers happen to be present, the quiet majesty of the enormous stone-built defenses and singular natural setting seem even more to evoke the former power of this strategically positioned citadel – once inhabited by kings, queens, warriors and priests during the great Late Bronze Age era of Greek heroes.

Mycenae has something for everyone: for the pragmatic viewer, it is a massive military bastion erected by social elites to control surrounding lands and peoples, including the almost equally impressive, secondary fortress at Tiryns some 15k to the southwest. For the more romantic, literary visitor, Mycenae represents a celebrated hilltop palace whose praises were once sung throughout the Greek world, around which still swirl the timeless stories, myths and distinctive personalities recounted by Iron Age bards and Classical playwrights.

“ Mycenae was once a military bastion and celebrated palace, around which, today, still swirl timeless stories, myths and distinctive personalities. ”

Homer, Greece’s earliest known epic poet, who may have lived sometime between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, describes Mycenae in his Iliad (Books 2, 4, 7) as a well–founded citadel, “wide wayed” (with broad streets) and “golden.” That Mycenae was indeed a city of gold is immediately apparent to visitors of the Bronze Age Gallery at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, where many golden objects – especially the so-called Mask of Agamemnon – remind us of the riches once enjoyed by this site’s noble residents. At Mycenae itself, as one approaches and passes through the Lion Gate (erected ca. 1250 BC), the wideness and grandeur of the prehistoric castle’s entrance also leaves a lasting impression. It is similarly from Homer that we first hear the name of Agamemnon, the ruler of Mycenae, who led his army to Troy. His domain, Homer recites, incorporated many islands and all of Argos, as well as territory stretching in the opposite direction toward “wealthy Corinth.”

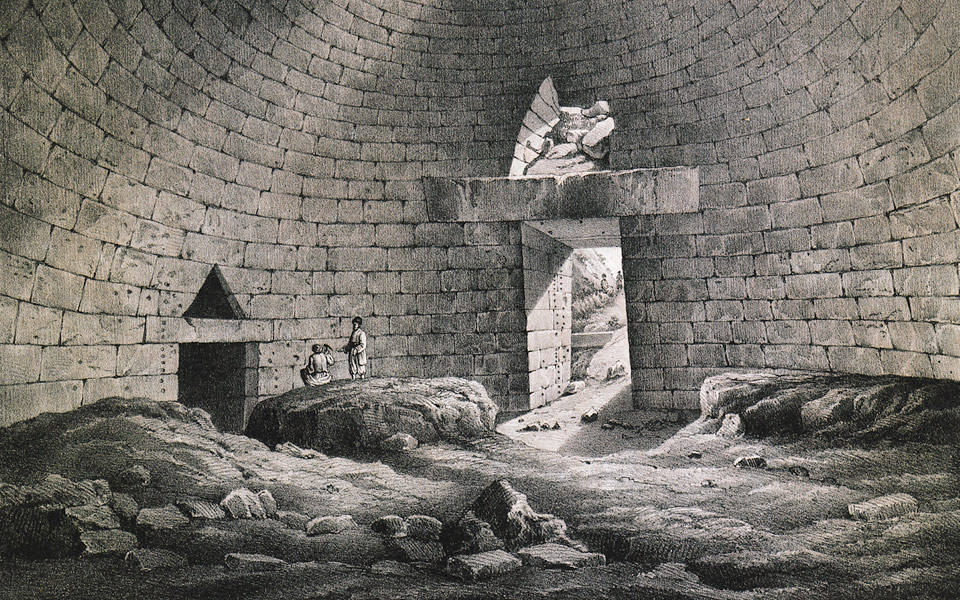

The entrance (dromos) to the “Treasury of Atreus,” actually a majestic, domed tholos tomb.

© Olga Charami

View of the interior of the Treasury of Atreus, by Edward Dodwell,1834. (Source: Aikaterini Laskaridou Foundation – Travelogues).

Founding legends for Mycenae relate it was ruled by two successive dynasties (Perseides, Pelopides), established respectively by the hero Perseus and Atreus, two grandsons of an earlier regional dynast, Akrisios. Perseus reportedly first settled at Mycenae after his scabbard tip auspiciously dropped onto the rocky hill. He is also credited with discovering the natural spring (Perseia) that eventually fed the fortress’ all-important underground fountain, still to be seen today (by flash- light) down a dark, narrow flight of stone steps descending some 18 meters into the earth. The gigantic wall stones visible around the Lion Gate, as well as those at nearby Tiryns, are said to have been placed there by the Cyclops at Perseus’ bidding. Mycenae’s later ruler Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus (king of Sparta) were the sons of Akrisios’ other grandson, Atreus, whose name in modern times has been linked to the site’s largest, best-preserved Mycenaean “beehive” tomb.

The so-called “Mycenaean,” a fresco from the Cult Center at Mycenae (13th cent. BC; National Archaeological Museum, Athens).

© Olga Charami

Bronze dagger with a lion hunt inlaid in silver and gold, Mycenae (National Arcaeological Museum, Athens).

For archaeologists, Mycenae also represents the “birth- place” of Greek archaeology, where, in the 1870s, Heinrich Schliemann began excavating in search of his beloved Homeric heroes and unearthed the golden death mask of “Agamemnon.” Schliemann’s finds, and those of subsequent excavations led by respected archaeologists including Christos Tsountas, Alan Wace, George Mylonas and Spyros Iakovidis, have revealed a complex, multi-phase site first fortified ca. 1350 BC. Inside the walls, are the royal cemetery (Grave Circle A); houses likely belonging to prominent officials, priests, military leaders and favored nobles; a typical Mycenaean palace (megaron) with a throne room containing a large circular hearth; royal apartments; and special workshops.

Outside the walls, in addition to an excellent site museum, are Grave Circle B; ivory and perfume workshops; common Mycenaean residences; and numerous “beehive” and other tombs, including the so-called grave of Clytemnestra and “Treasury” of Atreus. The latter’s construction, with its massive lintel block (120 tons), highlights the advanced engineering skills of the Mycenaeans – also evident in a stout stone bridge to the left of the road as one returns to the village of Mykines, in a second better-preserved example beside the Nafplio-Epidaurus road and in the still-towering walls and corbeled archways of Tiryns.

The Mycenaean “Warrior Vase,” once used for mixing wine at banquets (National Archaeological Museum, Athens).

The golden funerary mask of “Agamemnon,” discovered in Grave Circle A, Mycenae (National Archaeological Museum, Athens).

Like Mycenae, the hill of Tiryns had already been inhabited for more than a millennium when its enormous defensive walls (some almost 7 meters thick) were erected in the 14th- 12th centuries BC. The Upper Citadel featured a palace complex with a monumental gateway, a central court, a characteristic megaron and a network of private apartments with baths, light wells and drains. Also of interest are two arched galleries (possibly storerooms) and an unusual, circular building of Early Helladic date (2400-2300 BC) partly preserved beneath the later royal megaron. Schliemann excavated Tiryns, followed by Greek and German archaeologists. The Lower Citadel held residences, workshops and cult areas. Common folk lived outside the walls, where two nearby tholos tombs also indicate a royal cemetery. Colorful wall paintings from Tiryns offer an intriguing glimpse of well-coiffed Mycenaean ladies and a boar hunt with dogs.

MYCENAE

Mykenae (Prefecture of Argolida) • Tel.: (+30) 27510.765.85

• Opening Hours: From November 1 to March 31: 8:00-15:00 • April: 08.00-19.00, May until October 31: 08.00-20.00

• Admission: Full: €12, Reduced: €8

• Ticket is valid for the Archaeological Site, the Museum and the Treasury of Atreus

Step beyond Athens this autumn and...

From Mycenaean citadels to ancient stadiums,...