Neoclassical Architecture: From Greece to the World

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus (2nd c BC). Detail of a mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii (National Archaeological Museum)

© Visualhellas.gr

More than 23 centuries after he unexpectedly died in distant Babylon, Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) still seems to be a name that comes easily to many people’s lips – from young children first learning to tell jokes (“What’s purple and conquered the world?” “Alexander the Grape!”) to historians, anthropologists, linguists and opportunistic politicians striving even today to come to grips with the Macedonian commander’s stunning military achievements, to trace his cultural influence or to exploit his universal fame and appeal.

Alexander III was, and is, ancient Macedonia’s greatest native son, a brilliant, hugely confident, remarkably skilled young man, who grew up surrounded by royal luxury, hard-fighting, hard-drinking military men, self-serving, often murderous palace intrigue and especially the examples set through the relentless ambitions of his dynamic parents, Philip II and Olympias. Thanks to a slew of biographers both ancient and modern, including Theopompus, Plutarch, Arrian, Diodorus Siculus, Polyaenus and more recently Robin Lane Fox and Peter Green, we know much about Alexander, his character and his ambitions.

Alexander was born at Pella, then a prosperous coastal emporium that lay at the heart of a kingdom his father was already in the midst of expanding and consolidating into a powerful regional empire. He was the latest scion in the Argead Dynasty, which claimed descent from the divine hero Heracles. On his mother’s side, who hailed from wild Epirus, he was said to be related to the great warrior Achilles, a revered figure that played a formative role in Alexander’s thinking, self-image and actions right down to the end of his life. As a youth, he pushed himself to excel in fighting, to achieve great feats and to stand above the crowd. When he invaded Asia in 334 BC, he first stopped at Troy, where, accompanied by his closest, life-long friend Hephaestion, he paid his respects at the tomb of Achilles and ran a race naked in honor of his dead hero. In the end, eight months before his own death, Alexander was inconsolable at the passing of Hephaestion, much as Achilles had mourned his beloved Patroclus, and buried him in a similar (although far more extravagant) ceremonial style.

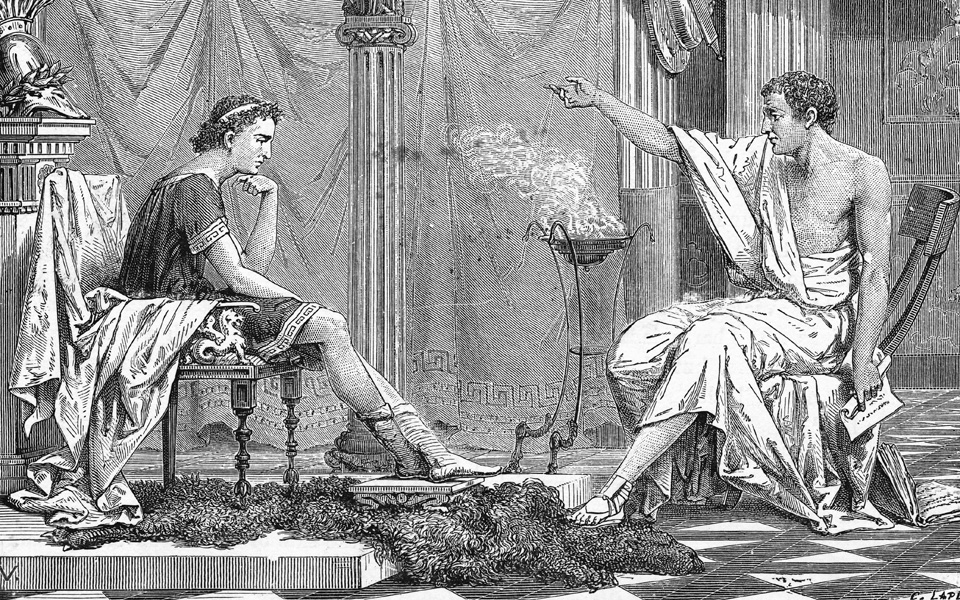

Aristotle Teaching Alexander the Great. Engraving by Charles Laplante, in vol. 1 of Louis Figuier’s Vie des Savants Illustres - Savants de l’Antiquité (Paris, 1866).

© Corbis / Smart Magna

Alexander’s legacy as an ambassador of Greek civilization survives in linguistic, religious and other cultural traces still evident in distant corners of Asia.

The greatest influences in Alexander’s early life were his tough soldier-father and his fiercely protective mother. Philip seems largely to have been absent from Pella, but, due apparently to his great military prowess and lack of paternal attention, he was dominant in Alexander’s mind – as a role model, but also as a competitor, whose acknowledgement the boy seemed desperate to gain. The well-known story of 8-year-old Alexander recklessly, but magnificently mastering the seemingly uncontrollable horse Bucephalas at Dion, in front of Philip and his father’s friends and functionaries, well illustrates his own character and the internal conflict that ultimately drove him to reach heights far beyond those of Philip.

Queen Olympias, on the other hand, spent much time looking after her young son’s best interests, particularly those concerning Alexander’s future ascendancy to the Macedonian throne. This led the prince himself to become constantly on guard to protect his own position and the way others perceived him. In another telling, well-known incident, at the wedding feast in celebration of Philip’s marriage to his fifth wife, Cleopatra Eurydice, in 338 BC, Alexander responded to an insult cast at him by the bride’s father, Attalus, concerning his legitimacy, by hurling a wine cup at the offending guest. When Philip, perhaps far into his cups, attempted to respond violently to his son’s rudeness, he slipped and fell, thus giving his son the opportunity to mock him: He who wants to invade Persia cannot even move from one seat to another without stumbling.

Olympias, mother of Alexander the Great, depicted on a gold pendant of the Roman era (Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum).

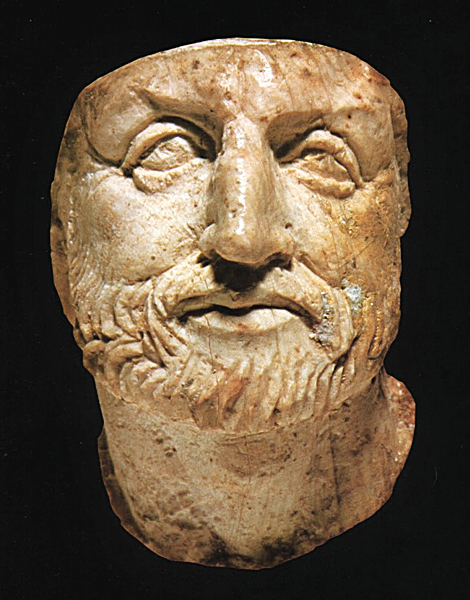

Head of Philip II, carved in ivory, from his tomb at Vergina (Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina).

Despite occasional bad blood, Philip looked after his son’s education and appears to have admired him. Alexander’s most influential teachers were Leonidas, a relative of Olympias, and especially the philosopher Aristotle. Leonidas taught him to be tough, to endure all-night marches and forced deprivations of food, while Aristotle cultivated his mind. Alexander occupied his days at Pella with reading, writing, swordplay, archery, horse-riding and learning to play the lyre.

Another memorable incident reveals several lasting character traits in Alexander: his tendency not to forget a slight and to welcome opportunities for vengeance; his sometimes exaggerated generosity; and his clever verbal agility. Leonidas had sternly chastised Alexander as a boy not to waste incense at sacrifices. Long afterward, in 332 BC, when Alexander had seized Gaza, the main Levantine spice emporium, he shipped back to the now-elderly Leonidas a potential fortune of 18 tons of frankincense and myrrh, as a remembrance of old lessons learned together.

Physically, Alexander was below average height, muscular, a fast runner, with wild blonde hair like a lion’s mane. He was fair-skinned and said to have different colored eyes (grey-blue, dark brown), sharply pointed teeth, a high-pitched, sometimes harsh voice and a quick, nervous gait. His head he held characteristically high, with his neck twisted slightly to the left. Alexander’s biographers mention something almost girlish, with a sense of suppressed tension, about his early portraits. He is remembered as intelligent, calculating and perceptive, but also impulsive, stubborn and violent-tempered.

Alexander Refuses to Take Water. Painting by Giusette Cades (1792, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg).

“Alexander’s thinking, self-image and actions right down to the end of his life. As a youth, he pushed himself to excel in fighting, to achieve great feats and to stand above the crowd”

Aristotle instructed the adolescent Alexander and a small student-body of other young princes and nobles at the Precinct of the Nymphs, a shady cave complex beside a river at Mieza, a village south of Pella in the so-called Gardens of Midas (today’s Veria-Naousa-Edessa region). Here, the philosopher oversaw Philip’s son in various studies, including Homeric literature, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, art, geometry, astronomy, rhetoric and medicine. Alexander developed an omnivorous curiosity for knowledge, later bringing on his Asian campaign a host of zoologists, botanists and other scientists. His keen interest in medicine encouraged a flexibility of mind and an ability to face any given situation, without preconceptions – qualities that eventually served him on the battlefield.

Alexander’s unparalleled skills as a military commander were largely learned from his father, initially tested in Macedonian and Greek lands, then honed and brilliantly demonstrated in Asia. He broke the back of the Persian Empire at Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, ultimately pushing as far eastward as northern India. His battle strategy relied mainly on the use of his elite officer-corps of Companion Cavalry and the impenetrable Macedonian phalanx armed with 6m-long spears (sarissas). By breaking the enemy’s central line with the phalanx, then aggressively outflanking and enveloping them with cavalry and archers, as he and Philip had done at Chaeronea (338 BC), Alexander overcame all opposition – even when charging war elephants were deployed against him in Persia and India.

The Battle of Alexander and Darius. Painting by Francesco Solimena (1735,Palace of La Granja, Madrid).

Alexander was a gifted leader, diplomat and propagandist, who presented himself to his Asian subjects as a god, son of Zeus-Ammon. In his inspired quest to meld East with West, he adopted Persian ways, brought conquered local officials into his imperial administration and encouraged his officers to intermarry with his newfound subjects. He himself married a Persian princess, Roxana, and spawned an ill-fated son, Alexander IV. In the end, he proved all too human, finally succumbing to disease, overdrinking or poison. He left behind an army in disarray and a host of squabbling successors. Nevertheless, his legend flourished. Today, Alexander’s legacy as an ambassador of Greek civilization survives in linguistic, religious and other cultural traces still evident in distant corners of Asia. His memory still sparks political wrangling and enriches the present-day cultural scene. Above all, his dynamic, undefeated military record will stand forever as one of the greatest achievements of ancient Greek history.

Discover how ancient Greek architecture inspired...

A major restoration project is bringing...

Four guesthouses set in unique landscapes,...

From temples and festivals to front...