8 Hidden Greek Museums Just Steps from the...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

Exhibition “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”.

© Stefanos Tsakiris

I was in the second decade of my life when I met Alexander Iolas. A patron of the arts. A troublemaker. Ironic. Shrewd. Brazen. Daring. Explosive. Unscrupulous. An adventurer. A man who belonged to an era after 2050.

It didn’t take me long to recognize his true genius. He took me to the Louvre. To MOMA. To the Pompidou. He stopped in front of this work or that and told me where to look. I learned more from his silence than I could have from even the wisest of interlocutors.

Like Socrates with his students, he drew out the best in me. He had the same influence on his artists, too, whom he pushed to create particular works of art that he “saw” or “lived” before they had even pulled out their materials to get to work.

A friend, more precious than the most expensive piece of jewelry. A spiritual father.

Iolas dancing. Photograph from Herbert List.

© Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art Collection

Alexandros Iolas was born in Alexandria in March, 1908. The son of a well-to-do family, Konstantinos Koutsidis was his given name, and he showed an early talent for music and dance. Years after we first met, he revealed to me that he had taken his pseudonym from Iollas, a friend of Alexander the Great and the imperial sommelier – who is rumored to have poisoned him.

At the age of fifteen, Iolas formed a spiritual bond with the poet Nikos Nikolaidis, who introduced him to Constantine Cavafy. At their first meeting, Cavafy gave him a poem, “Kaisarion,” written on one of those little pieces of paper that the Alexandrian poet used to give to his friends. After that, they began to meet more frequently. From Cavafy, Iolas learned his first lessons in princely modesty.

But their acquaintance also made him feel a new kind of unsettledness. He felt a new need to open his wings. He needed to let his true spirit develop, the kind of spirit which, even when its abilities are slight, always tries to surpass its limitations and those of its age, thus arriving at the peak of its creativity.

His dream was to travel to Greece. Cavafy himself encouraged him: “Go, if that’s where your soul is… I’ll give you letters of introduction myself, to Angelos Sikelianos, Dimitris Mitropoulos, Kostis Palamas…” Which is precisely what happened. Around 1927 Iolas came to Athens, leaving his mother’s family behind, and the cotton business for which his father, the cotton merchant Konstantinos Koutsoudis, had been grooming him.

"Story with a Chicken," Martial Raysse, 1986. Oil and acrylic on canvas.

© Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art Collection, Courtesy of Alexandros Iolas

Exhibition “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”.

© Stefanos Tsakiris

In Athens, aside from teachers and mentors who led him into a classic humanist education, he fell in love with ideas, creation, art. He studied piano with Dimitris Mitropoulos – becoming one of his best students – and dance with Vasos and Tanagra Kanellou. In 1931, at Mitropoulos’s encouragement, he continued his studies in Berlin. His intelligence, sensitivity, and great beauty helped him float to the top in his wanderings through artistic Europe in the interwar period.

In one instance, while still a student in dance school, he made his first appearance in Saltzburg, practically naked in the role of the ghost of Achilles in Glück’s Orpheus and Eurydice. He was paid the token amount of 10 shillings per month customarily given to students and “extras.” After the performance the great musician Bruno Walter and the director Max Reinhardt invited him to a dance the latter was throwing at his castle. When Alexander told them he didn’t have a dress coat, they answered in one voice, “Kommen sie so,” (Come just as you are). “I didn’t have a tuxedo, what was I supposed to do… so I went barefoot, wrapped in a white cloth,” he used to say when describing the event.

With the rise of Hitler in Germany, Iolas abandoned Berlin for Paris, where he first came into contact with contemporary art on visits to the French capital’s galleries. There he got his first glimpse of a painting by Giorgio de Chirico. In an interview he gave in 1971 he described that moment: “The first time the desire to own a painting came over me was […] around 1933. One day, I stopped short in front of a gallery on rue Marignan in Paris. A strange painting had attracted my attention. It was a tableau by de Chirico, the first modern painting I’d ever seen. It showed a wide square with a statue in the middle, and a train with smoke pouring out of its chimney crossing in the background. The title of the painting was Melancholy. I went into the gallery and asked, ‘What is that?’ and they answered, ‘It’s a masterpiece by de Chirico, you can buy it for $2,000.’ I kept visiting the gallery whenever I could, giving them small sums. After five years, it was finally mine. Those frequent visits to the gallery on rue Marignan were also what planted the seed for me to open my own gallery one day.”

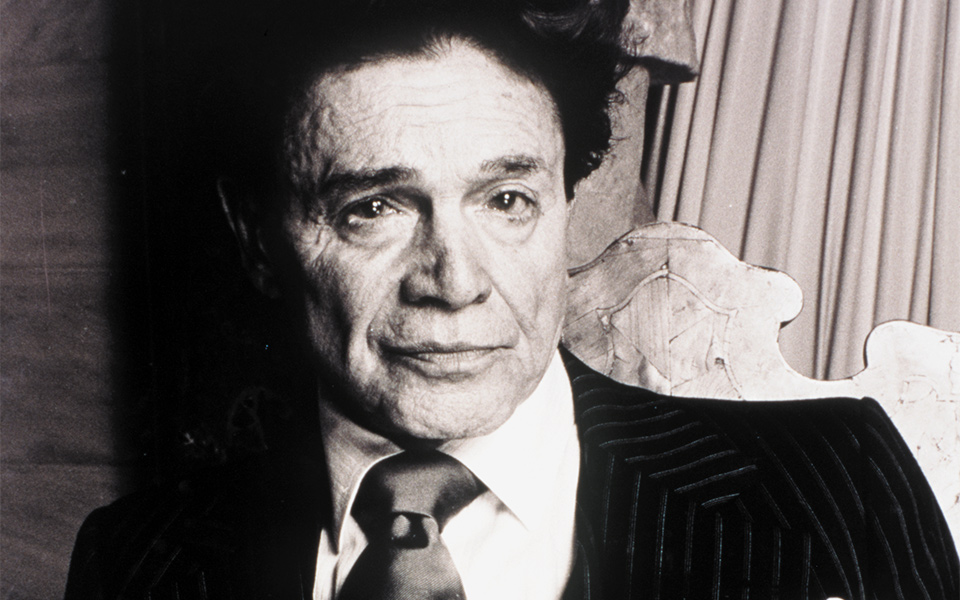

Portrait photography of Alexander Iolas.

Iolas the dancer, Berlin.

© O.K. Vogelsang

In the early 1940s, Iolas was living in the United States and dancing at the Metropolitan Opera of New York with George Balanchine in Orpheus and Eurydice. But in 1944, after a foot injury, he left his career as a dancer and turned towards the visual arts. In 1946, with the financial help of businesswoman Elizabeth Arden, he entered into a collaboration with the Hugo Gallery (owned by Hugo, a painter and grandson of Victor Hugo).

In the following years he presented, in firsts for the US, solo exhibitions of works by Max Ernst (1946), Rene Magritte (1947), Victor Brauner (1947), as well as the first solo exhibition of artwork by Andy Warhol (in June of 1952, with a series of illustrated stories by Truman Capote). In 1953, Iolas became the sole owner of the gallery in New York, which was renamed the Iolas Gallery.

All of the most avant-garde artists of the time exhibited in his gallery: Takis, Jean Tinguely, Yves Klein, Martial Raysse, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Jean Pierre Raynaud, Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne, Max Ernst, Dennis Oppenheim, Rene Magritte, Wols, Matta, Leonor Fini, Dorothea Tanning and others. Iolas would maintain friendships with most of these figures. In a large retrospective in Paris in 1971, Max Ernst declared: “I owe this success to Alexander Iolas, and I thank him.” Rene Magritte, also, praised the steadiness of their collaboration, saying: “Alexander Iolas started buying my work at the end of the war, almost everything I created, at a time when my work still hadn’t found a real market.”

In 1963, Iolas expanded his activities into Europe. He first opened a gallery in Geneva, with an inaugural exhibition of works by Max Ernst. Then followed galleries in Paris (in 1964 and which the arts press would call the “most active gallery in the country”), in Milan (1965), Zurich, and Rome. Most of the exhibitions were accompanied by luxurious catalogues, with introductions written by the likes of André Breton and Pierre Restany, although in many cases Iolas thought it important to include his own introduction, as for Magritte’s last exhibition. At all of his galleries he organized exhibitions by Greek artists, including Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, Tsarouchis, Fasianos, Tsoclis, Akrithakis, Bouteas, Marina Karella, Pavlos, Lazogas, and many others.

His exhibitions were exemplary; in 1969 his Paris gallery was described by the art historian Vasia Karkagianni-Karabelia as a “true gold mine for the history of art.” She wrote that nowhere else had she found “such wealth of information, including in the library of the Museum of Modern Art.”

In the 1970s, Iolas closed all of his galleries, ending with the Milan gallery in 1976. He thus kept the promise he gave to Max Ernst, that he would stop exhibiting upon Ernst’s death.

Exhibition “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”.

© Stefanos Tsakiris

Exhibition “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”.

© Stefanos Tsakiris

From the mid 60s Iolas started to spend a significant amount of time in Greece in his now-legendary villa in Agia Paraskevi (designed by the renowned architect Dimitris Pikionis), which he built on 2.5 undeveloped hectares purchased to the great surprise of others. There he housed his enormous personal collection of over 10,000 works of ancient, Byzantine, and contemporary art, and hosted some of the greatest figures of 20th century art: Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Rene Magritte, Giorgio de Chirico, Novello Finotti, Eliseo Mattiacci, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Max Ernst, and others.

One evening in particular has remained legendary, thanks to a dinner party for various celebrated figures, including Paloma Picasso. Iolas was in great need of a lady to complete the table, but none of his acquaintances were available to attend upon his very last-minute invitation. So he dressed his poor, deaf neighbor Michalis in a priceless dress, giving him a necklace and earrings and making him up to resemble one of Goya’s demonic old noblewomen. He introduced him as the Duchess of Agrinion, and no one questioned the “duchess’s” high birth or nobility, sitting there silently at the table. The episode, which Iolas recounted himself after the fact, became the stuff of legend in Europe. The story made its way all the way to Paris, where Ember d’Orsay wrote about it in Vogue.

Exhibition “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”.

© Stefanos Tsakiris

During his life, Iolas donated and sold works from his collection to major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Georges-Pompidiou in Paris. But his dream was for his collection to find a permanent home at a museum of contemporary art in Greece, which would rival the best museums in the world. “Because my country is poor,” he used to say. But his dream of founding a museum of that sort never became reality. He faced many difficulties, and certainly wasn’t helped at all by the unprecedented defamation he suffered at the hands of the Greek media in the early 1980s.

In 1984 he gave 44 works of contemporary art to the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, and shortly before his death he attempted to give the remainder of his astonishing collection to the Greek government. But the administration rejected his offer, and most of his collection was lost forever. On his death, the extraordinary villa-museum with its countless masterpieces was plundered, looted, and destroyed. Even its marble walls were torn to pieces.

Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas once said to me of Alexander Iolas: “He’s more Greek than the Greeks. Alexander Iolas will die in a masterfully theatrical work, which he himself will stage, with his life itself. His world is the very history of 20th-century art.”

Alexander Iolas died in June 1987, in New York.

“Alexander Iolas: The Legacy,” currently running at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, explores Iolas’ extraordinary life and his definitive vision. The MMCA – Greece’s first institution for Contemporary Art – was initially founded with his donation of nearly 50 seminal works. The pieces on display explore defining movements of 20th century western art, while correspondence, interviews, photographs, and objects narrate facets of Iolas’ life. A compelling persona, Iolas was an object of controversy, as seen for example in tabloid headlines contrasted with passionate letters of support from world cultural leaders. Through displays – his iconic fur coat, handwritten letters he received from Magritte, images of him as a dancer in his youth, and most engagingly his own thoughts and reminiscences – Iolas becomes more known to us, and no less mythic for it.

“Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”

Running until 20 January 2019

Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art

Egnatia 154 (In the premises of TIFF-Helexpo)

Tel. (+30) 2310.240.002

Open: Wednesday 10:00-18:00, Thursday 10:00-22:00, Friday 10:00-19:00, Saturday 10:00-18:00, Sunday 11:00-15:00, Monday & Τuesday closed

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

As the newly elected Pope Leo...

The charming port city of Volos...

As autumn deepens, Ioannina glows with...